Every September, Manhattan’s Chelsea gallery district launches into chaos after the art world’s summer vacation. Gallery-goers spill onto sidewalks, wait in lines to see particularly popular shows, and jump over puddles (dangerous given this year’s rain) in heels.

But at the photographer Trevor Paglen’s new exhibition at Metro Pictures, the crowd was decidedly different. Instead of sleek monochrome, visitors wore hoodies and T-shirts, and clutched messenger bags instead of totes. The shift is probably because Paglen’s project, uncovering the infrastructure of governmental surveillance, resonates with a decidedly more hacker crowd than minimalist sculpture.

Videos by VICE

Paglen’s show presents a wide-ranging investigation into the inner workings of the digital surveillance architected by the NSA and Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters in conjunction with companies like Google, Yahoo, and AT&T. As art exhibitions go, it’s uncommonly topical, especially because given our ongoing inaction on outlawing NSA initiatives, society seems to need constant reminding of its own surveillance to feel motivated to do anything about it.

The show isn’t not about malevolent Powerpoint policy presentations or invisible trackers. Paglen makes the actual physical structures of surveillance visible, training his camera on military intelligence complexes, active drones, and the undersea cables that deliver data from around the world through the United States—the same cables that the NSA tapped to syphon data.

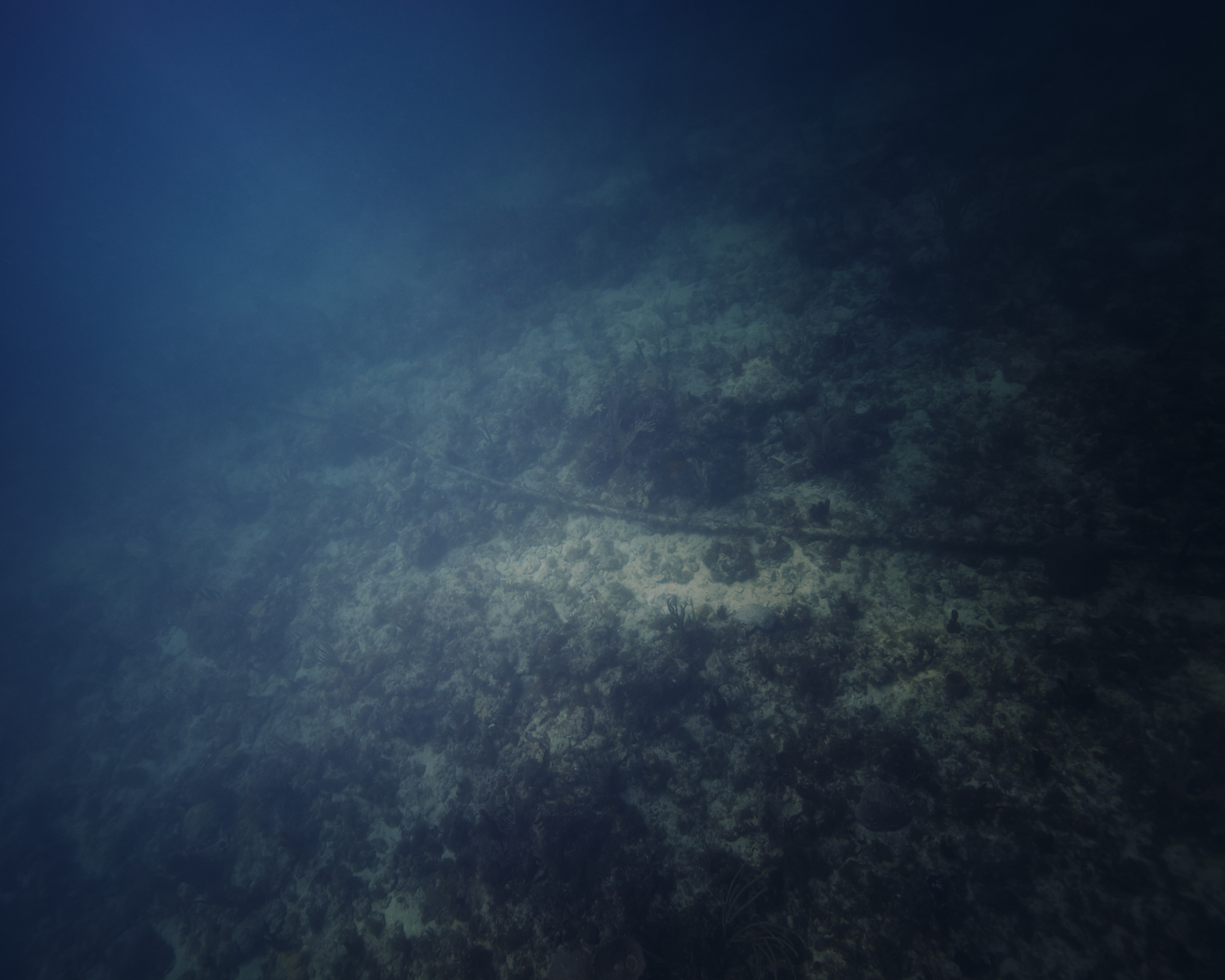

Columbus III NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean, 2015. Image: Trevor Paglen

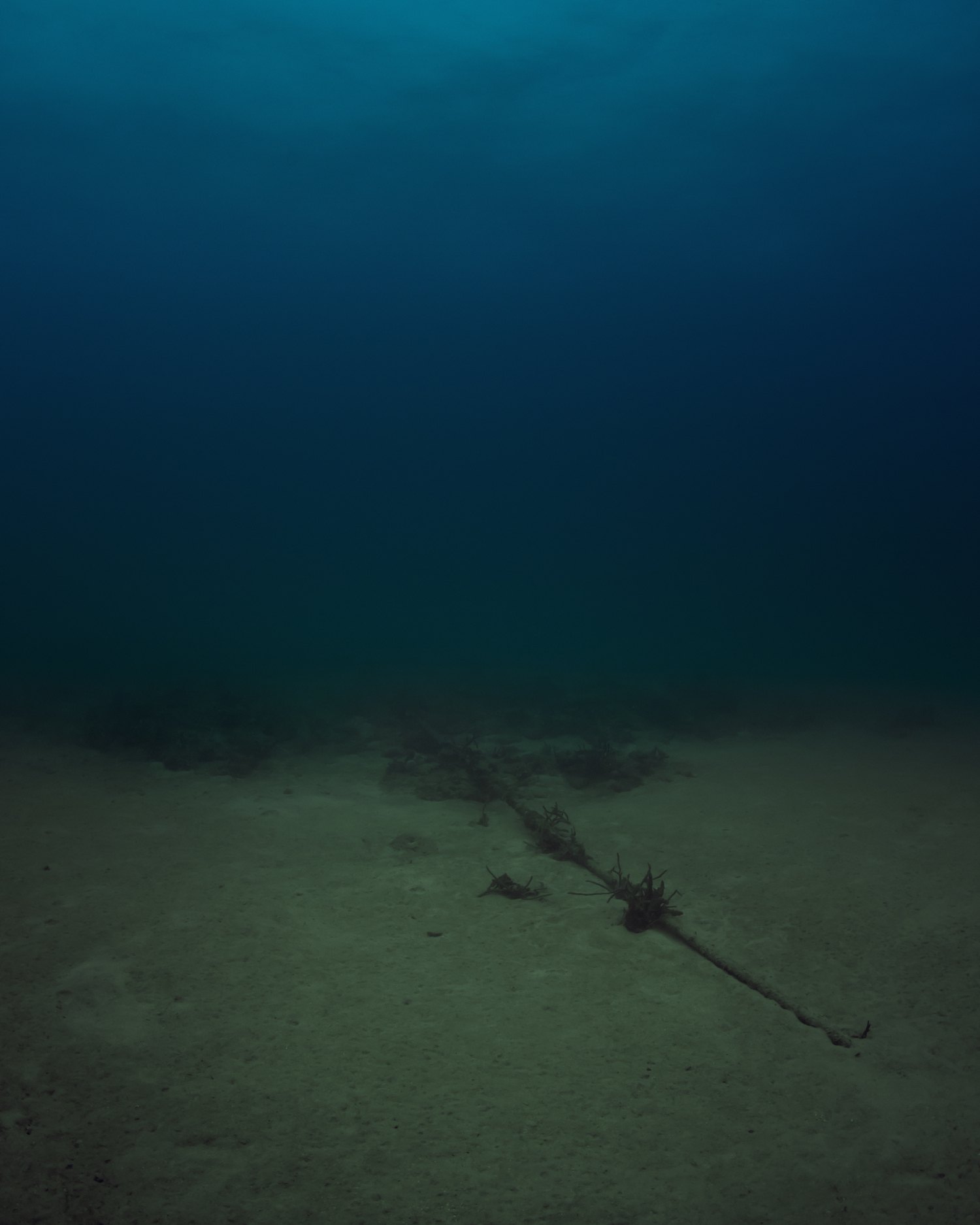

These last photographs form the backbone of the Metro Pictures show. From a distance, the prints look like Mark Rothko paintings: dark and ethereal, the light moving through the ocean water turning it various shades of turquoise, green, and dark blue. Then, you notice the cable, a wire running along the ocean bottom, at first picturesque and then eerie and paranoia-inducing when you remember what it does. The photo titles, which are the cables’ actual names, are similarly mysterious and suggestive: “Maya-1,” “Columbus III,” “Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1).”

To create the series, Paglen learned how to dive and started searching for the undersea cables’ choke points, the spots at which the physical networks of different continents come together. “I used this information to basically make giant search patterns, like drawing a square on a map and putting the GPS coordinates in there, before diving down with a team to shoot,” he told VICE.

Many of the cables land in California, where the artist did some of his dives. What’s striking about Paglen’s work is how close his discoveries are to home. The infrastructure that he’s shooting is not exotic or incomprehensible, it’s just hidden to the public eye, the same way that the ridiculous military patches for secret units that the artist discovered in an earlier body of work were, until Paglen published them.

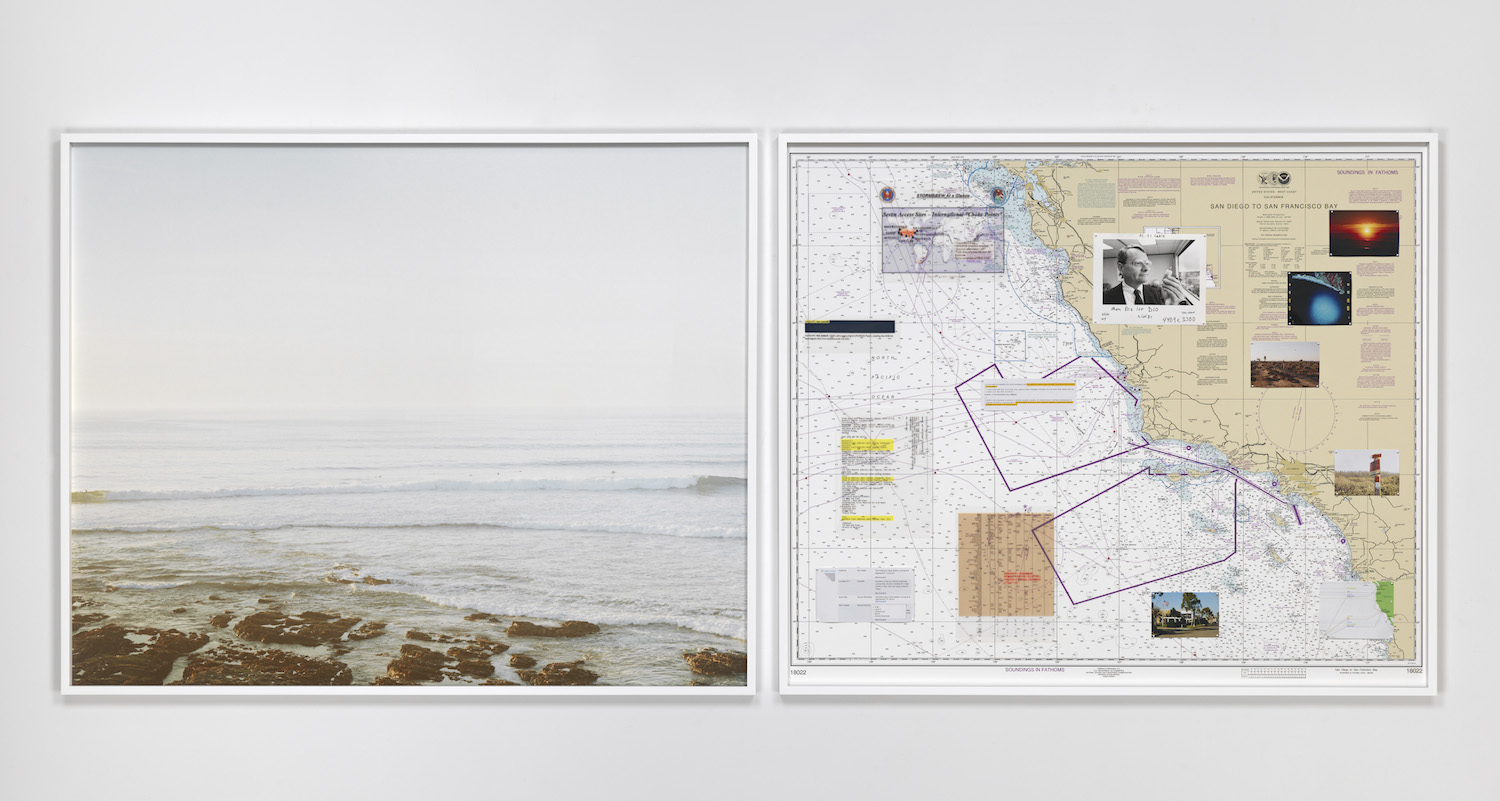

NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Morro Bay, California, United States, 2015. Image: Trevor Paglen

The exhibition brings to mind an earlier social definition of the artist as an explorer, a pioneer, and a vital public critic that has been occluded by the past decade of art market expansion. Like Manet’s “Execution of Emperor Maximilian” of 1869 that depicted the death of the eponymous Austrian colonial emperor of Mexico or “The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David, Paglen’s work is purpose-built to provoke viewers by confronting them with hidden reality.

Not unlike a photojournalist, Paglen seeks out potent images and captures them. But his fluency in the vocabulary of conceptual art and art photography makes the work carry more enduring heft. “Eighty Nine Landscapes” is a two-screen video that occupies an entire gallery at Metro Pictures. It shows long shots of the landscape of surveillance: satellite installations, the placid shorelines that conceal undersea cables, and NSA listening stations with bulbous sphere buildings like a sinister Epcot.

These are durational videos that might riff on Andy Warhol’s eight-hour film of the Empire State Building. But they also come straight out of Paglen’s work on CITIZENFOUR, fellow surveillance activist Laura Poitras’s documentary on Edward Snowden. The placid landscapes are visual irritants. They are beautiful and compelling, but also contain a certain sour note. Something is off. What exactly are we seeing, and why are we seeing it? The answer to the puzzle only comes with the reveal of blanket surveillance as pervasive as the ground itself.

Paglen’s work is its own form of leak, unveiling dark spots that we easily overlook in our rush to go about our lives aided by the convenience of digital technology.

Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1) NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean, 2015. Image: Trevor Paglen

For all its potency, there’s an issue with Paglen’s work, as well as that of his paranoia-hipster coterie of Poitras, Appelbaum, and the likes of Julian Assange. As much as it makes a strong critique, it also fetishizes surveillance, turning it into a badge of personal honor, aestheticizing it until it seems almost… cool? Like the stylish rebellion of punk or the iconoclastic clothes of Rei Kawakubo, what first exists as critique so often gets co-opted into fashion. Paglen’s shots of far-off drones piercing diaphanous sunsets would make great Hermes scarves.

As a form of activism, if not as art, Paglen is strongest when he stays away from polished images. In the show is “Autonomy Cube,” a plexiglass box encasing a computer that anonymizes all the network data that passes through it, created with Appelbaum. There’s also a scrolling video that lists the NSA’s absurd code names: “Astute Chameleon,” “Avenger Seawolf,” “Banana Glee.” Much as the NSA does, Paglen weaponizes information.

The Snowden leaks are retreating further into the past. The outrage is waning, and every major bill to end the NSA’s farthest reaching programs has stalled in Congress. Paglen’s work refreshes our memory and puts the fact of these abuses in front of us once more. And as the packed gallery showed, everyone is looking.

Perhaps it takes a different form of confrontation, one that artists excel at, to make us see what’s right before our eyes. As the visitors splash from gallery to gallery across the neighborhood’s wide, dark streets, I can’t help but think of the data being absorbed from their glowing phones, the threat of airborne cameras heavy in the sky.