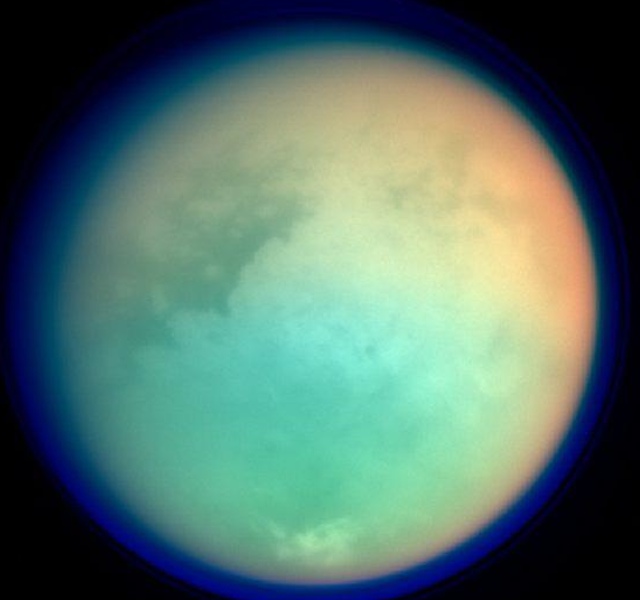

Concept drawing of Titan’s surface. Image: NASA

When it comes to tracking down extraterrestrial life, most scientists operate under the assumption is that aliens are likely water-dependent. After all, water played a central role in nurturing Earth's rippling biodiversity, so it's natural to regard this magic ingredient as crucial for kickstarting lifeforms on other worlds.But perhaps this emphasis on water casts too small a net, excluding unhydrated worlds with promising properties. That's the view taken by an interdisciplinary team of researchers based out of Cornell. In a study published on Friday in the journal Science Advances, the team get creative with biology by designing a hypothetical cell capable of surviving in a waterless environment."The lipid bilayer membrane, which is the foundation of life on Earth, is not viable outside of biology based on liquid water," the authors write in the study. "This fact has caused astronomers who seek conditions suitable for life to search for exoplanets within the 'habitable zone,' the narrow band in which liquid water can exist.""However, can cell membranes be created and function at temperatures far below those at which water is a liquid?" they asked.To ground this question in the physical universe, the Cornell team focused on simulating a cell that could survive on Saturn's fascinating moon Titan—the only moon in the solar system with a thick atmosphere, and the only world outside Earth that supports liquid on its surface. With surface temperatures of about -290 degrees Fahrenheit, Titan supports water only as ice. The moon's rivers, lakes, and seas instead flow as liquid methane, and its bedrock and atmosphere are bursting with hydrocarbons, which are important building blocks for life on Earth.Generally speaking, life on Titan hasn't been regarded as much of a slam dunk as life on worlds like Europa, which is thought to contain more liquid water than Earth. But its hyperproductivity of complex organic molecules makes it a compelling candidate nonetheless, and a perfect testing ground for imagining water-independent organisms.The Cornell team was led by molecular dynamics specialist Paulette Clancy, and co-authored by chemical engineer James Stevenson and Jonathan Lunine, an expert on the Saturnian moon system. From these diverse perspectives, they conceived of a cell which they dubbed an "azotosome," derived from the French word "azote" meaning "nitrogen."

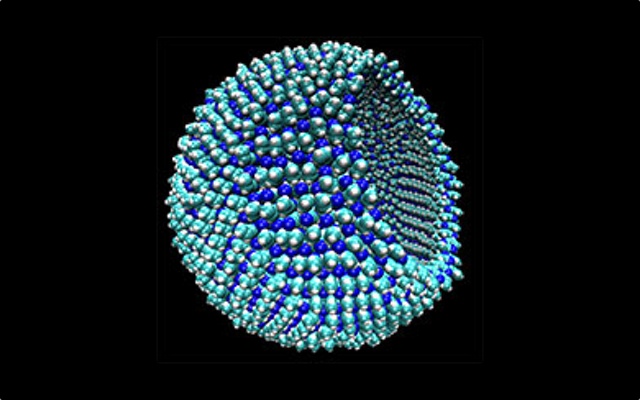

With surface temperatures of about -290 degrees Fahrenheit, Titan supports water only as ice. The moon's rivers, lakes, and seas instead flow as liquid methane, and its bedrock and atmosphere are bursting with hydrocarbons, which are important building blocks for life on Earth.Generally speaking, life on Titan hasn't been regarded as much of a slam dunk as life on worlds like Europa, which is thought to contain more liquid water than Earth. But its hyperproductivity of complex organic molecules makes it a compelling candidate nonetheless, and a perfect testing ground for imagining water-independent organisms.The Cornell team was led by molecular dynamics specialist Paulette Clancy, and co-authored by chemical engineer James Stevenson and Jonathan Lunine, an expert on the Saturnian moon system. From these diverse perspectives, they conceived of a cell which they dubbed an "azotosome," derived from the French word "azote" meaning "nitrogen." This hypothetical lifeform would be comprised of nitrogen, carbon, and hydrogen, and would have the same flexibility and durability at cryogenic temperatures as our familiar hydro-operated cell membranes do at room temperatures.The team modelled several different molecular scenarios looking for the ideal combination for the environment, and discovered that a toxic compound known as acrylonitrile—used in the manufacture of acrylic plastics and fibers—would be especially conducive to life on Titan. Clancy and Stevenson, a pair of chemists who normally work on semiconductors, were particularly taken aback by the hardiness of the simulated cell."We're not biologists, and we're not astronomers, but we had the right tools," Clancy said in a Cornell statement. "Perhaps it helped, because we didn't come in with any preconceptions about what should be in a membrane and what shouldn't. We just worked with the compounds that we knew were there and asked, 'If this was your palette, what can you make out of that?'"The notion of producing a speculative design of a lifeform for an environment is a wonderful reversal of the evolutionary reality, in which environments sculpt life. It's also a welcome departure from the mindset that extraterrestrial beings are most likely to develop in Earthlike conditions. There's nothing at all wrong with that approach; in fact, it makes loads of sense. But as the new study demonstrates, it's a lot of fun to untether ourselves from our planetary prejudices, and think outside the astrobiological box.Perhaps Stevenson, who was inspired by Isaac Asimov's essay "Not as We Know It" put it best: "Ours is the first concrete blueprint of life not as we know it."Whether or not such beings actually do exist on Titan is a question for future studies. But to know that life is, at least, conceivable in such an alien environment expands the aperture of the search for otherworldly beings.

This hypothetical lifeform would be comprised of nitrogen, carbon, and hydrogen, and would have the same flexibility and durability at cryogenic temperatures as our familiar hydro-operated cell membranes do at room temperatures.The team modelled several different molecular scenarios looking for the ideal combination for the environment, and discovered that a toxic compound known as acrylonitrile—used in the manufacture of acrylic plastics and fibers—would be especially conducive to life on Titan. Clancy and Stevenson, a pair of chemists who normally work on semiconductors, were particularly taken aback by the hardiness of the simulated cell."We're not biologists, and we're not astronomers, but we had the right tools," Clancy said in a Cornell statement. "Perhaps it helped, because we didn't come in with any preconceptions about what should be in a membrane and what shouldn't. We just worked with the compounds that we knew were there and asked, 'If this was your palette, what can you make out of that?'"The notion of producing a speculative design of a lifeform for an environment is a wonderful reversal of the evolutionary reality, in which environments sculpt life. It's also a welcome departure from the mindset that extraterrestrial beings are most likely to develop in Earthlike conditions. There's nothing at all wrong with that approach; in fact, it makes loads of sense. But as the new study demonstrates, it's a lot of fun to untether ourselves from our planetary prejudices, and think outside the astrobiological box.Perhaps Stevenson, who was inspired by Isaac Asimov's essay "Not as We Know It" put it best: "Ours is the first concrete blueprint of life not as we know it."Whether or not such beings actually do exist on Titan is a question for future studies. But to know that life is, at least, conceivable in such an alien environment expands the aperture of the search for otherworldly beings.

Advertisement

Advertisement