Brian Merchant is the author of The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone. He was a senior editor at Motherboard from 2012 to 2016 and is the editor of Terraform. To kick off our week of stories about the cultural, social, and political influence of the iPhone, I asked him to write about what he learned while reporting the book. -Jason Koebler

The iPhone is the best-selling product, maybe ever. The iPhone is the most popular model of mobile computer yet created. The iPhone is the result of some of the most inspired user interface design and software engineering in the technology industry’s history. The iPhone is the thing you turn around and head back home for, even if you’re already halfway to work, and you’re already late.

Videos by VICE

The iPhone is also a source of perpetual misery for factory workers who assemble hundreds of them by hand a day. The iPhone is a collection of metals, materials, and elements that are mined, sometimes in brutal conditions, on nearly every continent. The iPhone is an engine of accelerated connection and distraction; a touch-operated command center for the apps and games that pull with increasing gravity on our lives.

The iPhone is all of these things, and plenty more. I hope I’ve gotten a line on some of them—I spent most of the last couple years investigating the origins and impacts of what Steve Jobs called the “one device,” and distilled the results into this book. The investigation took me—along with some of my colleagues here at Motherboard—from the lithium mines of Atacama in the driest desert on Earth to the largest hacker gathering in North America to the sprawling megafactories of Shenzhen in China.

And there’s plenty more to examine still—this week, Motherboard will be running stories that explore the ways the iPhone has influenced and altered our culture. Because while it’s obvious that the iPhone has changed much of how we consider our lives, it still isn’t exactly clear what it is, and what it means to us.

The first important thing to note about the iPhone, I think, is that it wasn’t a breakthrough or even new technology on its own. It is, as Computer History Museum curator Chris Garcia explains, what’s called a confluence technology—each unit of iPhone is a container ship of countless prior inventions, ideas, and labor hours. The amount of human sweat, brainpower, and suffering pumped into each one is almost incomprehensible. The idea that the iPhone is any one thing, or has any single inventor—even Jobs—is absurd. It took a veritable invisible city of co-conspirators, spanning generations, to make it possible—and a factory-sized real one to put it together. If there’s anything the iPhone distinctly is not, it is the mere brainchild of Steve Jobs. So what is it?

A smarter phone

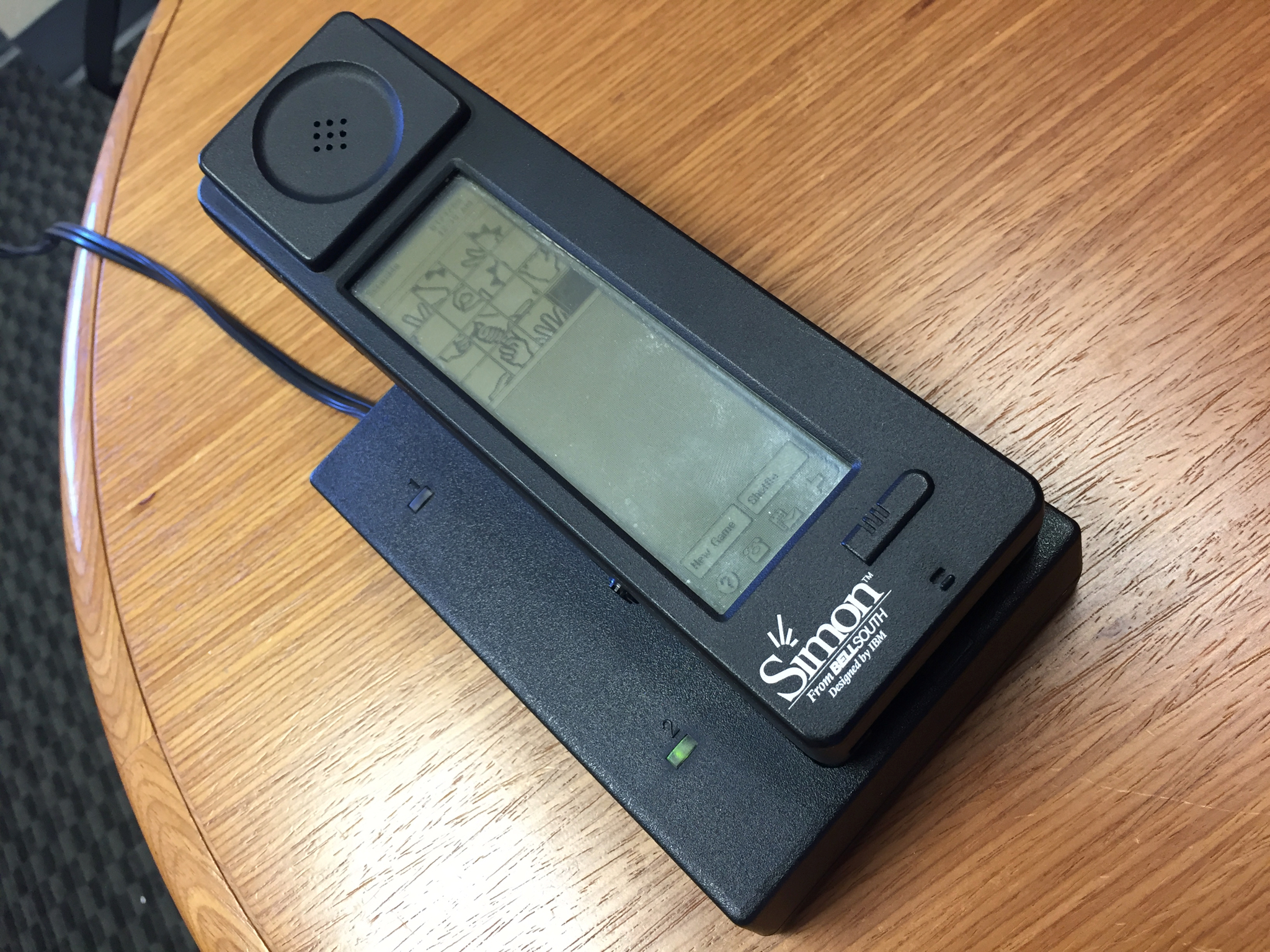

When Frank Canova Jr. showed me the first smartphone, the Simon—which he built for IBM in 1993—I was struck by how iPhone-like it was. Not in shape or design—this thing was huge; it had to be to fit the chips of the day—but in function. Nearly a decade and a half before the iPhone, another black rectangle with a touchscreen and a grid of apps, another mobile computer, hit the market. And flopped. The technology wasn’t ready, as Canova laughs today—”It’s all about timeframes.” Yep: One way to look at the iPhone is as the culmination of over a hundred years’ worth of humanfolk dreaming up portable audiovisual communicators. Since the final decades of the 1800s, we’ve been imagining devices like the “telephonoscope” that would let us connect to friends and family regardless of distance, and stream entertainment into the palm of our hands.

So it makes sense that, now that we’ve got what we’ve always wanted, we’re hooked. As the mobile technology historian Jon Agar says, “It’s almost vanishingly rare that we pick a new device that we always have with us… Clothes, a Paleolithic thing? Glasses? And a phone. The list is tiny. In order to make that list, it has to be desirable almost universally.”

Which it is, now.

Augmenting, distracting

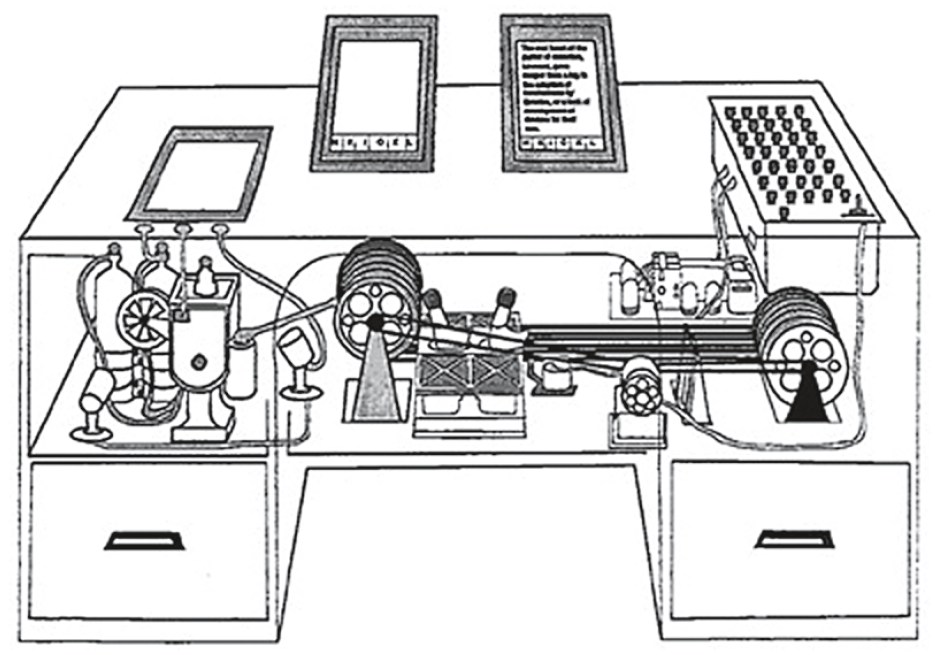

The iPhone is the first device that became both ubiquitous and versatile enough to fit something resembling the true definition of human-computer symbiosis—the sort of computerized knowledge augmenter that pioneering technologists like Vannevar Bush, JR Licklider, Doug Engelbart, and Alan Kay believed would help us navigate an increasingly complex world. That, they thought, was the ultimate promise of computing.

When I went to visit Kay in his Brentwood home, I asked him how the iPhone stacked up half a century later. Problem is, he laments, the iPhone and its ilk are designed more to consume media and information than to engender new ways to create or order it. One of the great questions about the iPhone is whether it adds more to society at large than it detracts—do the omnipresent GPS, education apps, and connective power of social media make up for a world of omnipresent lostness in info, pay-to-play gaming apps, and time-draining excesses of social media?

Everywhere I went over the course of reporting the book, I saw evidence to count towards both: Artist-types wandering the streets of Paris with their nose in a phone. A table of men in thawbs laughing at YouTube videos around a hookah table in Abu Dhabi. Protesters organizing and documenting a march in Los Angeles. Chinese iPhone factory workers utterly absorbed into their smartphones during a noodle break.

On a drive home from Silicon Valley after a long weekend of interviewing iPhone pioneers, on the I-80, a man blew past me in a Kawasaki motorcycle, doing at least 80—while one-handedly thumbing through his phone. I’m no exception—there are probably entire cities whose skylines I don’t remember because my face was glued to my social media feeds. Yet after perusing iPhone black markets in Shenzhen, examining the booming app scene in Nairobi, or observing the lithium mines in Chile, the first thing I’d do after getting through with the day was always the same; FaceTime with the family back home. The iPhone moves us into a web of great power, great responsibility, and perhaps great risk.

“We should have included a warning label,” Kay says.

Apple’s most important product

The iPhone accounts for two thirds of the most valuable company on the planet’s total revenue. Well over a billion iPhones have been sold since 2007. According to one analysis of financial data of the S&P 500 companies that produce consumer products, the iPhone is more profitable than cigarettes. The iPhone is, clearly, Apple’s most important product.

Jobs had an inkling that would be the case. During the frenzied development process, he told his team: “You guys, you probably have no idea, what you’re doing is more important than what we did with the original Mac.” And he’d be right, thanks to a handful of key innovations.

The world’s introduction to touch tech

The iPhone introduced multitouch technology to the masses, and it came via Wayne Westerman, a brilliant PhD student who founded a company called FingerWorks after prototyping a touch-friendlier replacement to the traditional keyboard. Apple bought Fingerworks in 2005 to integrate that multitouch technology—which Jobs claimed Apple invented—into the iPhone.

The most popular computer user interface, ever

Likewise, an unsung team of user interface designers—Bas Ording, Imran Chaudhri, Greg Christie, Freddy Anzures, and others—that created the look and feel of the software that now powers our lives, and engineers like Richard Williamson, Henri Lamiraux, Nitin Ganatra, and Andy Grignon, led by Scott Forstall, brought it to life. Jony Ive’s industrial design team, and Tony Fadell and David Tupman’s hardware engineering team, grafted function onto form.

The iPhone is their electronic work of art—the invention of a team of dedicated, ambitious, and sleepless Applers who delivered Steve Jobs the finest totem to his legacy. [The iPhone is also, of course, home to the App Store—the secret ingredient that propelled it to success, and which Jobs didn’t quite want in the first place.] That user interface has since been copied by the even-more-ubiquitous Android, which has conquered the corners of the world the iPhone has not.

A collection of raw materials drawn from every corner of the globe

The iPhone takes advantage of a globalized supply chain that allows the company to draw inexpensive metals from every corner of the globe, assemble them in China, and ship them back around the world. The iPhone is the product of a winding supply chain that begins in places like the tin mines of Bolivia, where miners pry tin out of the increasingly unstable walls of Cerro Rico, a centuries-old silver mine that once bankrolled the Spanish Empire.

There are similar mines on every continent—cobalt in the Congo, rare Earths in Inner Mongolia, aluminum in Australia. Mining, even in the age of smartphones—perhaps especially in the age of smartphones—is still glaringly brutal work. In the mines I visited in Bolivia, where Apple’s suppliers source some of its tin, dozens of miners die from cave ins every year. And these materials will be used for a wide array of components and ultimately the thing itself—the iPhone is a tiny museum of metals precious and common, deadly to obtain and mundane. It’s not obvious, but it helps; deep in the mine, to remind yourself; this is part of the iPhone. This is where it starts. My colleague Jason and I didn’t last a half hour down there.

The iPhone is a physical object built by hundreds of thousands of hands, in China, in factories the size of cities. I’ve been inside them—they are grim, soulless places; the barracks on the frontlines of consumerism. Overwork, exploitation, and even suicides still plague the workers that make them possible, long after Foxconn’s suicide epidemic made headlines in 2010.

Foxconn’s Longhua factory. Image: Brian Merchant

After I slipped into the world’s most famous iPhone factory, I saw this firsthand.

The iPhone is also destined to become e-waste; guarded against mainstream repairability by Apple’s Pentalobe screws. The iPhone is the embodiment of the yearly upgrade cycle. The iPhone is also the most secure mobile computer on the market, but a prime target for hackers and tinkerers. The iPhone is the vessel for the first mainstream AI, Siri. The iPhone is a masterclass in business marketing, and in the fruits of corporate secrecy. The iPhone is, perhaps, our greatest computer, communicator, and commodity.

It’s a collaborative project on an incomprehensible, generation-spanning scale, like much of our best technology, only better. Apple was both brilliant and at the right place at the right time.

The iPhone was in the right place at the right time

“So much of it is timing and getting lucky,” former iPhone engineer Evan Doll told me (Frank Canova told me the same thing, from the other end of the spectrum—”It’s all about timeframes,” he said, as to why his Simon never took off). “The ARM chips that powered the iPhone had been in development for a very long time, and maybe fortuitously had reached a happy place in terms of their capabilities,” Doll said. “The stars aligned.”

They also aligned with lithium-ion-battery technology, and with the compacting of cameras. With the accretion of China’s skilled labor force, and the surfeit of cheap metal flows around the world. The list goes on,and inside Apple itself. “It’s not just a question of waking up one morning in 2006 and deciding that you’re going to build the iPhone; it’s a matter of making these non-intuitive investments and failed products and crazy experimentation—and being able to operate on this huge timescale,” Doll says. “Most companies aren’t able to do that. Apple almost wasn’t able to do that.”

Because it was, the iPhone is the most profitable, most-imitated, most routine-reorienting, most popular device. The iPhone is everywhere, and we rarely stop to interrogate the one device we carry everywhere. The iPhone just is.

Motherboard staff will be exploring the cultural, political, and social influence of the iPhone for the 10th anniversary of its release. Follow along.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Nintendo -

(Photo by Leonard Ortiz/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register via Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Credit: Thomas Trutschel/Photothek via Getty Images