This summer, the Food and Drug Administration warned hospitals to stop using a line of drug pumps because of a cybersecurity risk: a vulnerability that could allow an attacker to remotely deliver a fatal dose to a patient. SAINT Corporation engineer Jeremy Richards, one of the researchers who discovered the vulnerability, called the drug pump the “the least secure IP enabled device I’ve ever touched in my life.”

There is a growing body of research that shows just how defenseless many critical medical devices are to cyberattack. Research over the last couple of years has revealed that hundreds of medical devices use hard-coded passwords. Other devices use default admin passwords, then warn hospitals in the documentation not to change them.

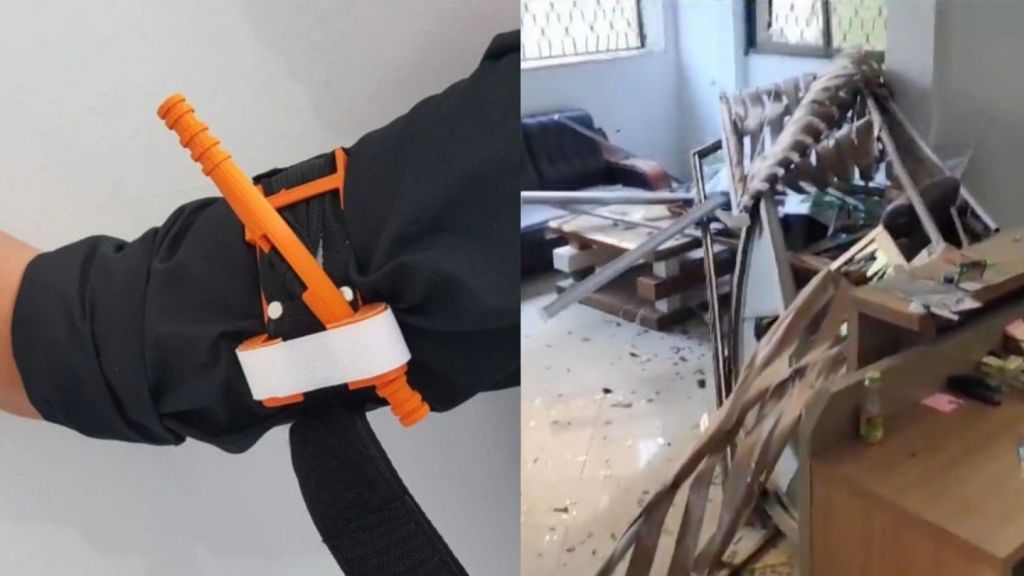

Videos by VICE

A big part of the problem is there are no regulations requiring medical devices to meet minimum cybersecurity standards before going to market. The FDA has issued formal guidelines, but these guidelines “do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities.”

“In theory you could sell a bunch of medical devices without ever having gone through a security review,” the well-known independent medical device security researcher Billy Rios told Motherboard.

The FDA disputed this. In an email, Suzanne Schwartz, director of emergency preparedness/operations and medical countermeasures in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, argued that the formal guidelines document “explains that manufacturers should consider cybersecurity risks in the device risk analysis that is required as part of design controls.”

How many 10-year-old computers would you trust with your life?

“Design controls are indeed legally enforceable,” she wrote, under CFR 820.30(g), a federal regulation that mandates pre-market device testing, but does not specifically mention cybersecurity testing requirements.

Given the current parlous state of medical device security, it’s not clear what’s worse—no regulations, or regulations that aren’t being enforced.

Either way, security researchers say the FDA is developing a clue. SAINT Corporation security researcher Jeremy Richards, who, along with Rios, discovered the Hospira drug pump vulnerability, says he has been surprised by the government support he has received recently.

“The FDA, FBI, DHS, ICS-CERT [the US government agency that issues cybersecurity advisories]…they are all moving in the right direction but moving at the typical government pace,” he wrote in an encrypted email. “They (FDA) have guidelines that need some work but they recognize there is an issue.”

Because the result of disclosing a medical device security vulnerability is often a lawsuit, rather than a security patch, Richards is especially appreciative that the government is pushing back against those kinds of tactics.

“ICS-CERT in particular has been very helpful and has gone through the trouble of contacting and interfacing with Hospira on my behalf,” he wrote. “This is HUGE for me. I have worked on devices in the past and have had device manufacturers threaten legal action. Having the full weight of the FDA and the DHS behind me when dealing with the vendor makes all of this possible.”

As a result of the security vulnerabilities disclosed by Rios and Richards, the FDA advised hospitals to stop using Hospira’s Symbiq Infusion system.

So the FDA gets it. DHS gets it. ICS-CERT gets it. So why don’t we have any regulations yet? Or, if the FDA’s legal argument holds, when will the existing regulations be enforced?

“From what I can tell the FDA operates with a public safety mandate but they can’t show their teeth until a public safety issue occurs,” Richards wrote.

To make matters worse, according to Richards, the development life cycle for medical devices can take five to ten years, or more. At a recent talk at DerbyCon about cybersecurity vulnerabilities in medical devices, researcher Scott Erven told the audience about a new pacemaker that was recently approved under an expedited process that took 12 years.

“Hospitals need to vote with their money and buy devices from manufacturers that put a priority on safety.”

“The challenge that medical device manufacturers face is that from concept, to design, to fed approval to deployment can take five years,” Richards wrote. “If you’re looking at a device that has been deployed for five years it is very likely it’s a ten-year-old computer.”

How many 10-year-old computers would you trust with your life?

“It’s a tough problem to solve,” he wrote. “Regulations are just a start but they are the only place to start. Vendors won’t do it on their own (though they are starting to try in the last 3-4 years). Hospitals need to vote with their money and buy devices from manufacturers that put a priority on safety. If hospitals prioritize security because regulation say they must then vendors will too.”

The FDA agreed. In a prepared statement, Schwartz wrote, “Managing cybersecurity threats is a shared responsibility and the FDA collaborates with cybersecurity researchers, software engineers, manufacturers, government staffers, information security specialists and healthcare professionals to address this issue.”

In the meanwhile? Fingers crossed that no one hacks your drug pump next time you’re in the hospital.