There’s a struggle going on between companies that want to drill for shale gas in the UK countryside and campaigners trying to stop them. Now, the struggle is waging online.

Revelations about how Facebook data has been used to target individuals for political ends continue to emerge. But after the Cambridge Analytica scandal of earlier this year, the story has taken an unexpected twist: Facebook is being used by oil and gas companies to clamp-down on protest.

Videos by VICE

Three companies are currently seeking injunctions against protesters: British chemical giant INEOS, which has the largest number of shale gas drilling licenses in the UK; and small UK outfits UK Oil and Gas (UKOG), and Europa Oil and Gas.

Among the thousands of pages of documents submitted to British courts by these companies are hundreds of Facebook and Twitter posts from anti-fracking protesters and campaign groups, uncovered by Motherboard in partnership with investigative journalists at DeSmog UK. They show how fracking companies are using social media surveillance carried out by a private firm to strengthen their cases in court by discrediting activists using personal information to justify banning their protests.

The material was submitted to support the companies’ case that campaigners intended to illegally disrupt their activities or trespass on their land. The companies all stress they do not seek to restrict lawful forms of protest, but argue that activists should not be allowed to unduly disrupt their lawful business activity.

Anti-fracking campaigners have described the use of injunctions to stop protest around potential fracking sites as “an unprecedented restriction on our fundamental rights.” They say the injunctions against “persons unknown” are “draconian” and “anti-democratic.”

According to the official court documents seen by Motherboard, the private security firm which conducted some of the surveillance on behalf of the oil and gas companies is Eclipse Strategic Security.

Facebook surveillance

Among the documents submitted by the oil and gas companies to the courts to justify their injunctions, there is a distinct focus on Facebook surveillance.

As a consequence of the companies including the posts in the hearing bundles, they become part of the public record, with anyone able to request access to the documents.

The documents reveal that the companies have used Facebook to engage in widespread and intrusive social media surveillance of individual campaigners and their private lives. In one witness statement on behalf of INEOS, CEO of Eclipse Raymond Fellows describes his company as having been “retained” by INEOS “to provide security services.” He tells the court that “a common tactic” by “activist individuals/organisations” is to:

“…use social media to announce a ‘call to arms’ by publicising the details of a ‘peaceful’ protest on Twitter or Facebook or their own organisation’s website.”

The resulting “mass of protestors”—many of whom are “law abiding citizens who wish to exercise their legal right to protest”—is, Fellows alleges, exploited by “a small hard core group of activists… to slow the police down and to prevent them from retaining the security of a site.”

Included in the evidence supplied by the oil and gas companies to the courts are many personal or seemingly irrelevant campaigner posts.

Some are from conversations on Facebook groups dedicated to particular protests or camps, while others have been captured from individuals’ own profile pages.

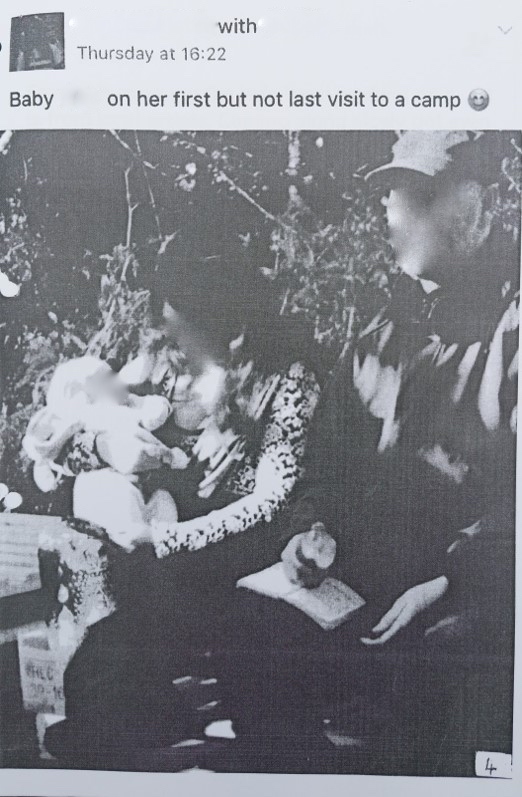

For instance, a picture of a mother with her baby at a protest was submitted as part of the Europa Oil and Gas case. Another screenshot of a post in the Europa bundle shows a hand-written note from one of the protesters’ mothers accompanying a care package with hand-knitted socks that was sent to an anti-fracking camp.

One post included in the UKOG hearing bundle shows two protesters sharing a pint in the sun—not at a protest camp, nor shared on any of the campaign pages’ Facebook groups:

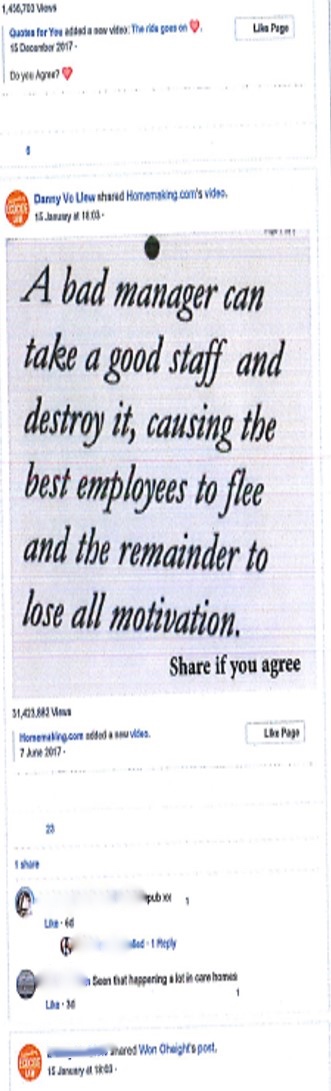

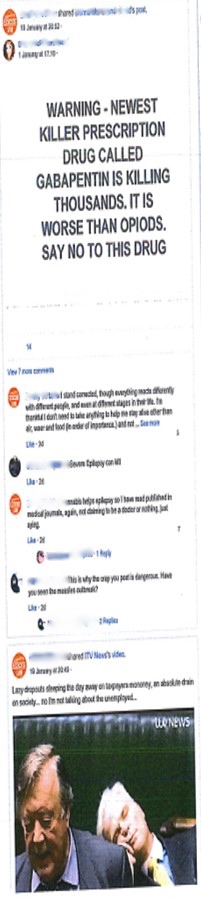

A screenshot from INEOS’s hearing bundle shows posts from a protester to his own Facebook wall regarding completely unrelated issues such as prescription drugs, and a generic moan about his manager.

It is not always clear how such posts are being used against these activists except to portray them in a bad light, and a judge could disregard them as irrelevant to the case. But their often personal nature raises questions about how these companies were scrutinising the private lives of campaigners to justify shutting down their protests.

In 2011, the UK government ordered a public inquiry led by Lord Justice Leveson into the culture, practices and ethics of the British press after a leading tabloid newspaper was convicted of phone hacking. One of the activists subject to surveillance, Jon O’Houston, who has been part of the Broadford Bridge Protection Camp, said he felt it was equivalent to the phone hacking cases, which led to the Leveson review.

“What’s said in the groups is generally taken either out of context or cherry-picked”, O’Houston told Motherboard. “When taken out of context, you can make anything look bad or good.”

Despite his posts being used to strengthen the case for injunctions against protesters, he said he wouldn’t necessarily change his behaviour on social media.

“I don’t think I’d ever change the way we operate our groups. There’s too much information there already. If someone wants to go back five years and have a look at what was going on in these groups five years ago, they could do that,” he said.

“It would be very difficult if we stopped using Facebook as a platform,” he added. “We would lose so much of that important stuff. In a way, it’s got us trapped.”

Generally, the groups were open to the public, meaning anyone could join (and record) the messages. But in some cases, private groups appear to have been infiltrated.

Group administrators were contacted by DeSmog UK for comment to ascertain whether they were aware of the surveillance of their activity. They were pseudonymous on Facebook and most chose not to disclose their identity in correspondence. Many responded that they were “angry” and “loathed” how their words had been turned against them. But few expressed shock.

One administrator said the main regret was failing to alert members that participating in the groups could provide useful leads for companies seeking to make a case.

“I now feel angry and regretful that lovely and entirely law-abiding members of our local community who joined the group weren’t more strongly encouraged to set up alternate anonymous Facebook accounts so their privacy wasn’t invaded by the unpleasant people who conducted the monitoring,” Lucy Barford, administrator of the Voice for Leith Hill group, said.

Another administrator called the surveillance “creepy.”

“For the industry to pay security and surveillance services to go through our pages, groups, and timelines can have a chilling effect with some,” an administrator for the Frack Free Sussex Facebook group said. “We try not to let it affect us.”

Environmental protesters have a long history of being subjects of clandestine surveillance. In 2011, it was revealed that officer Mark Kennedy had gone undercover to infiltrate campaign groups including environmental activists on behalf of the Metropolitan Police. Campaigns to reveal the full extent of such infiltration are ongoing as part of the SpyCops movement. The UK-based cosmetics company Lush recently ran a controversial advertising campaign to raise awareness of the issue.

Such familiarity with police surveillance could explain why many campaigners were not surprised to find their online activity submitted as part of the court cases.

Some said they were open on Facebook even when they suspected the companies were watching. Stephen Hall, administrator for the Balcombe and Beyond group, said “it was taken for granted that pro-fracking elements would join the Facebook groups as we actively canvassed for local support. Our mindset was we have nothing to hide when all we are attempting to do is save our environment.”

Some of the group administrators said they may tone down their messages on Facebook after seeing how they were used in the injunction hearings, but none suggested they would stop using Facebook altogether, with one admitting, “I loathe it, yet remain on Facebook feeding them.”

Private Security

The court documents make it clear that much of the surveillance has been conducted by a company called Eclipse Strategic Security, whose directors gave witness statements on behalf of the fracking companies in the injunction hearings.

Among Eclipse’s services, according to a brochure on the firm’s website, is ‘Threat Analysis and Monitoring’ through “investigation and surveillance operations” involving “Access to geo-spatial, real-time mapping of harvested, multi-source, social media posts.”

Eclipse has ties to oil companies, the police and military networks, and one director is a former British soldier who has expressed support for far-right groups online.

Court documents confirm that Eclipse has worked with INEOS, UKOG, Europa and other major fracking companies for the last three years at least, providing security services at the Leith Hill, Broadford Bridge and Horse Hill sites, and “closely monitor[ing] the activities of protesters” at Preston New Road, Kirby Misperton, and Barton Moss. The documents show that Eclipse began carrying out concerted surveillance of activists from 2016 onwards.

Records at Companies House, a government registry of UK companies, show Eclipse’s income increased 10-fold between 2016 and 2017, the year in which the fracking companies that had hired Eclipse sought injunctions.

Eclipse’s CEO, Ray Fellows, previously worked for a company that delivered security training for BP, Shell, and ExxonMobil. He has also worked as a security consultant for INEOS.

INEOS declined to comment on this story. UKOG, Europa and Rocksavage International did not respond to requests for comment.

Many Eclipse directors and staff members have ties with UK military and police networks with expertise in surveillance. In 2017, Fellows attended a joint meeting with trade association UK Onshore Oil and Gas, the National Police Coordination Centre and the UK’s Counter Terrorism Intelligence Unit to address concerns about the risks posed by “militant activists.”

Others have worked with private defence firms such as Aegis Defence Services, which operated in Iraq and Afghanistan under Pentagon contracts. Eclipse did not comment for this article but did respond to an email about the Facebook profile of one of its directors, which showed personal support for far-right groups including the Infidels of Britain which advocates for a white British state and is “opposed to multiculturalism.” An HR manager for Eclipse said that an internal investigation would be conducted into “the veracity of the allegations” which are viewed “in a very serious light.”

Injunction progress

One of the most worrying things about the oil and gas companies’ injunctions is that they are against “persons unknown.”

That means that anyone who could reasonably expect to know about the injunctions is covered by them. Given the wide remit of the injunctions, that could be anyone who visits the fracking sites.

This is important given Eclipse’s statement to the courts that the majority of the protestors are “law abiding.” But instead of targeting alleged “hard core activists” accused of disrupting peaceful protests, the oil and gas firms’ approach can justify the wholesale prohibition of protests.

INEOS has a temporary injunction in place, which is currently going through the appeal process. UKOG is due in court in early July, while Europa’s injunction is currently in place. The UK’s most high profile fracking company, Cuadrilla Resources, was just granted an injunction for its site in Lancashire.

By applying for injunctions against “persons unknown,” the fracking companies prevent individual protesters from being able to defend their case in court as individuals. This potentially gives the companies a litigious advantage.

By continuing to pursue “persons unknown” while closely surveilling individuals, the companies are potentially bypassing the protesters’ democratic rights by preventing them putting across a defense in the injunction hearings. And they’re using Facebook to do it.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Acid Wizard Studio -

Hesham Sallam -

Mr. Timoty/Getty Images