Uzbeki women picking cotton. Uzbekistan is the world’s third largest exporter of cotton

Advertisement

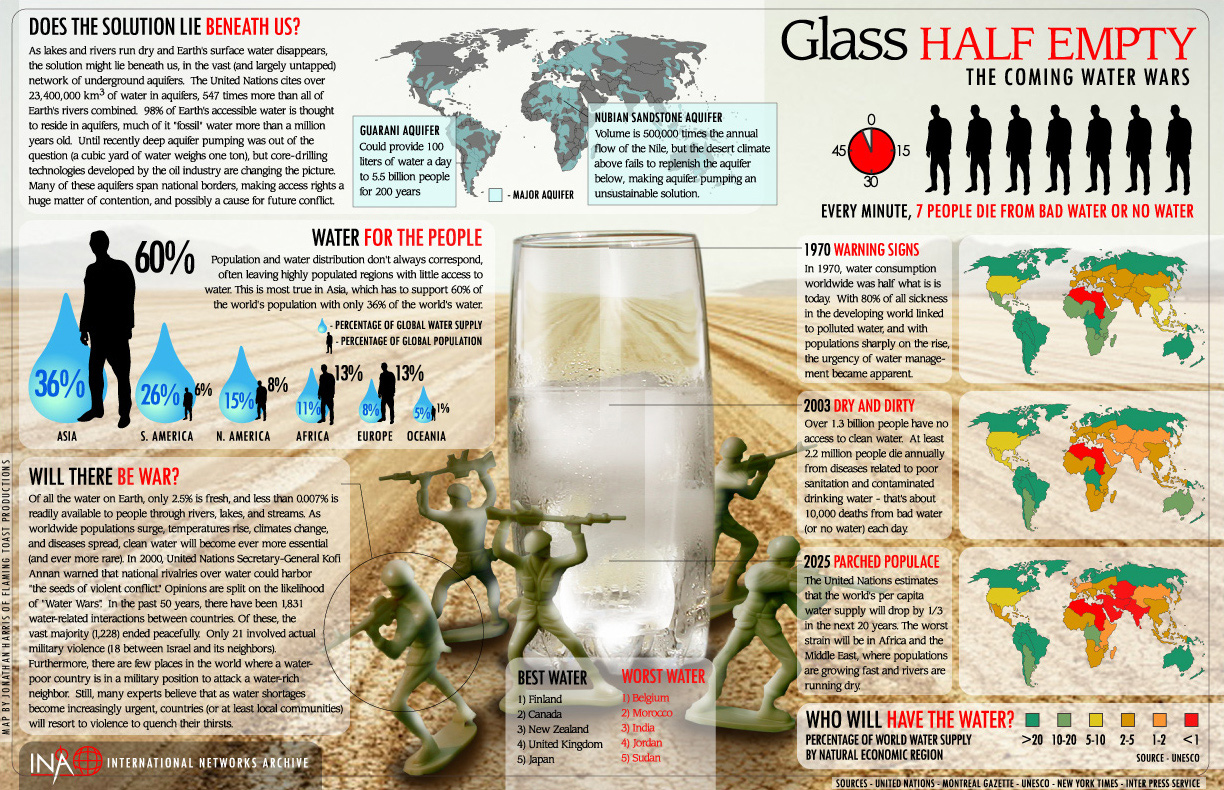

A map of global water tensions (Al Jazeera)

The situation is fluid

Advertisement

Infographic courtesy International Networks Archive, Princeton University; by Jonathan Harris, Number 27

Advertisement