Danny J. Sanchez is obsessed with opals—but not with the way they look set in silver jewelry or embedded in rock. Hours quickly pass as he journeys through each one, using a composite microscope and a complicated ad-hoc photography setup. Magnified, these stones reveal multicolored, strange and beautiful worlds.

“My whole thing is landscape, or at least space-scape, or some place to transport myself,” he told me in his studio, a back room of his house, which his grandparents built near Los Angeles. “I just keep returning to opal. It’s sort of the language I speak.”

Videos by VICE

Sanchez’s unusual hobby is called “photomicrography”—i.e. using a microscope to magnify a subject and take its picture. But while others do it for scientific purposes, such as studying tiny creatures, Sanchez is one of few who focus exclusively on gemstones, and purely for fun: “I need it. I love it. It’s like my joy,” he said.

When I visited his studio, Sanchez demonstrated his setup using a Mexican opal he’s been working with for almost a year. With the microscope set to a magnification of 50x, craggy reddish terrain emerged, and a blue “sky” lit up with neon green speckles as Sanchez rotated it.

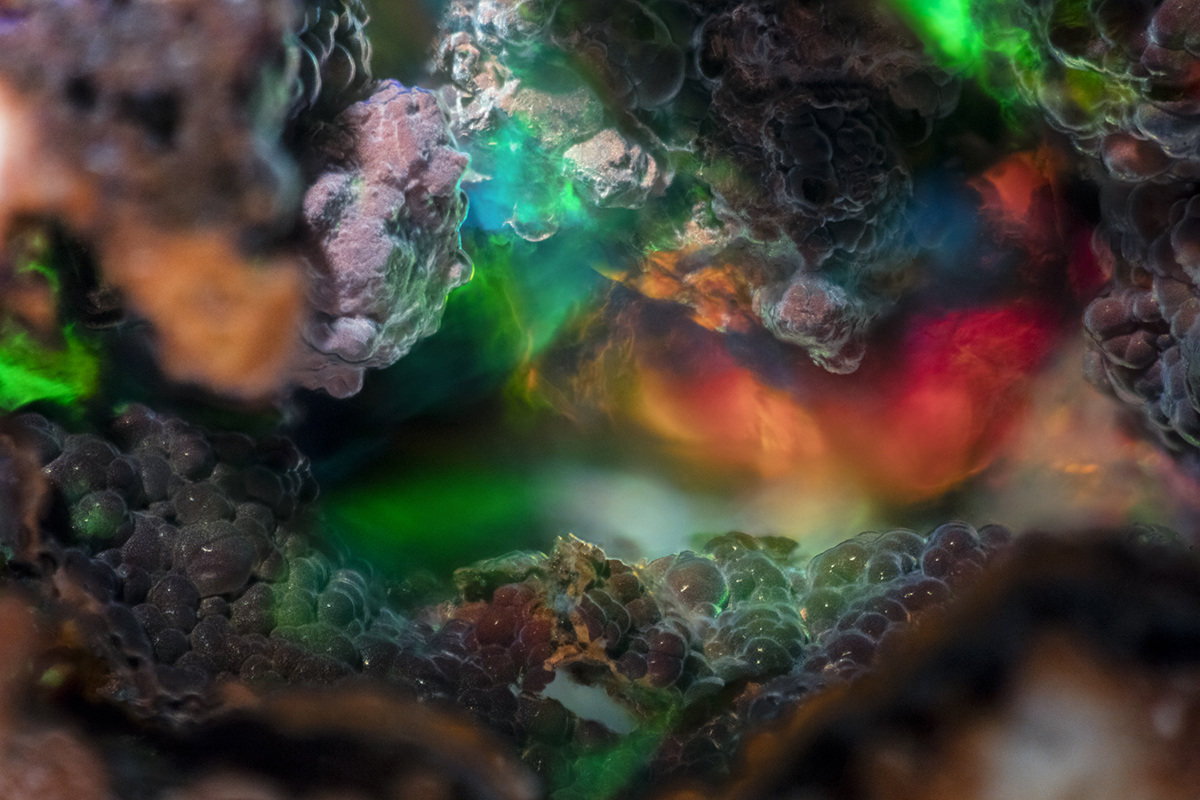

The same opal was the subject of this image he made recently (multiple Instagram followers likened it to the Aurora Borealis).

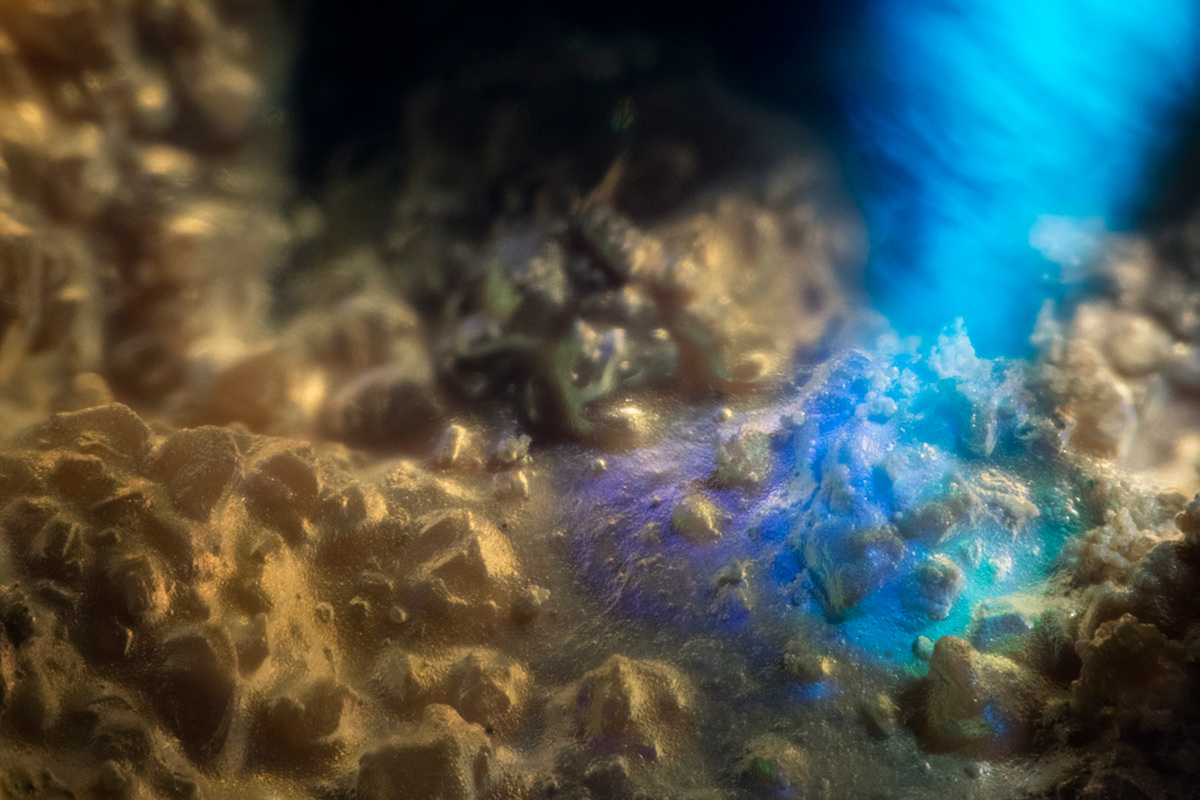

He changed out the stone for an Australian boulder opal. Suddenly, the microscope seemed to be peering deep in the ocean, as if we were floating toward a coral reef.

Here’s a finished image by Sanchez of the same type of opal:

Sanchez’s self-described “weird pursuit” began in 2004. While studying at the Gemological Institute of America in Carlsbad, California, he fell in love with the ultra-magnified images of precious stones in his textbook. “These photos really touched that child-like part of me — that part of me that’s always, always ready to wonder at something,” he said.

He bought his first microscope about 11 years ago—a bulky white device still sitting on a shelf in his studio. He enjoyed experimenting with it, but couldn’t get the images he wanted out of his stones. Eventually, he invested in a high-quality microscope with a changeable lens, as well as a heavy table to absorb vibrations and a variety of small, movable lights. He also figured out how to mount a camera on top of the microscope and precisely control the focus with a computer program. Much of his equipment came from eBay and Craigslist, and some of the smaller custom parts, like a lens cap, he made himself.

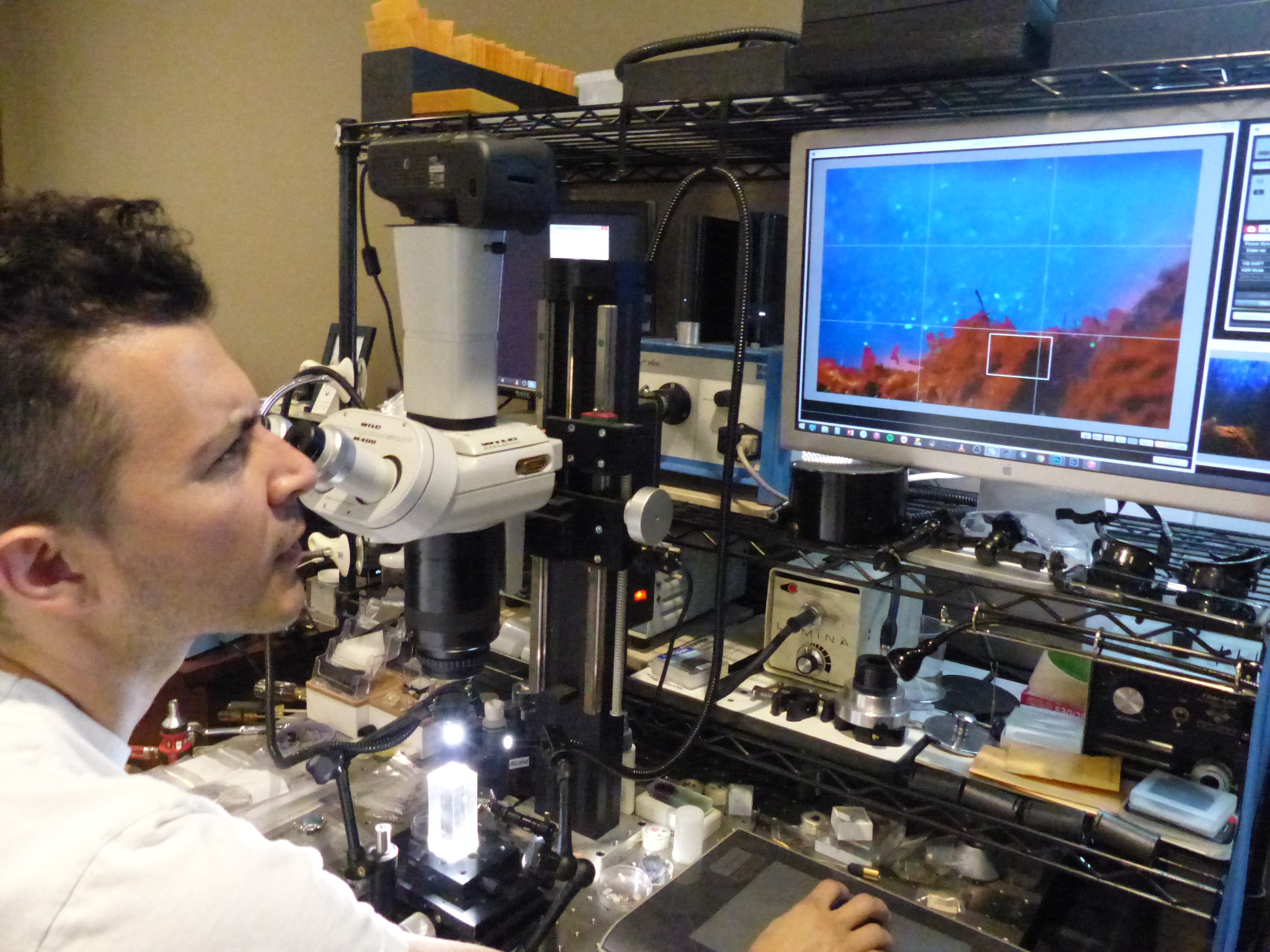

Sanchez’s studio setup. Image: Elizabeth Landau

Now, Sanchez sells prints of his work online and exhibits in galleries. He was invited to show his work at a gallery during the famous Art Basel festival in 2015. He keeps a day job in an estate jewelry store, but in his free time he’s in his photomicrography playground.

With the exception of opals, Sanchez often goes after stones often considered lower quality because of features called “inclusions”—other minerals inside the stone, gas, liquid or fractures that diminish the purity of the gem. To gemstone dealers, they are detractors. To Sanchez, they are gateways to other realms.

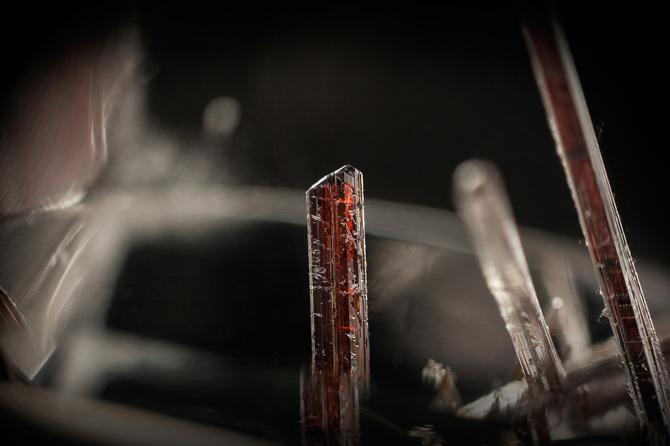

In one of his iconic works, Sanchez captures what looks like an eight-sided crystal floating in space. But that distinct shape is actually negative space within the surrounding spinel crystal. Even cooler: In nature, spinel grows in that octahedron shape, so the image reflects its “natural habit,” Sanchez said.

None of Sanchez’s final products are really single images. He uses a technique called “focus stacking,” where he combines dozens or sometimes even hundreds of images of the same view, but varies the focus by less than one millimeter. The result is a profound sense of depth.

This view inside a Mexican opal, for example, is composed of 163 individual shots. “I hate to have favorites, but, this one is definitely one of them,” he said.

Sanchez delights in watching people realize that his colorful, otherworldly images are, in fact, gems that exist. Connecting people with that “sense of awe” is part of why he enjoys making these images. “Everyone loved rocks when they were a kid,” he said. “It’s great to help remind people of that feeling.”

See more of Danny J. Sanchez’s work at his website.

More

From VICE

-

Malte Mueller/Getty Images -

Malte Mueller/Getty Images -

-

Apple AirTag clipped to a backpack — Credit: Photo by James D. Morgan/Getty Images