Dinosaurs and space.

Two subjects, so rich in visual splendor and childish wonder, that have been the most reliable gateways to science for generations. Dinosaurs, with their exotic shapes and sizes, are powerful manifestations of deep time. Deep space—the universe beyond Earth, with its promise of discovery and adventure—has beckoned to humans for millennia.

Videos by VICE

But because dinosaurs were very much confined to Earth—a limitation that was central to their doom—it would seem preposterous to imagine them as spacefaring creatures. And yet, as chaos theorist Ian Malcolm put it in Jurassic Park, life finds a way (at least in fiction).

Type “dinosaurs in space” or “dinosaur astronauts” into any search engine and you will see countless wild and creative visions: The Silurians of Doctor Who take dinosaurs into space in the aptly-titled 2012 episode, “Dinosaurs on a Spaceship.” The Voth depicted in Star Trek: Voyager are descendants of intelligent hadrosaurs that left Earth for greener pastures in the aftermath of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. Dinosaurs piloting rocket ships is a running gag in Bill Watterson’s Calvin & Hobbes.

There’s also lesser-known fare, like Anne McCaffrey’s Dinosaur Planet series, and the space opera Captain Raptor. Allen A. Debus’ book Dinosaurs in Fantastic Fiction includes a whole chapter outlining the history of saurian aliens, which he calls “exodinosaurs.” And there’s the 1987 animated show Dinosaucers, which featured an unforgettable opening theme that may as well be the unofficial anthem for the kaleidoscopic genre of space dinosaurs.

This impulse to position dinosaurs in space has even spilled over into real science. The chemist Ronald Breslow toyed with the idea of exodinosaurs in a 2012 study that was labeled his “space dinosaurs” paper by the journal Nature. It is also now literally true that dinosaurs have reached space, if only in death, as multiple fossils of dinosaur species have been sent into orbit.

How did this vision of extant dinosaurs, out there roaming the universe, become such a popular and beloved science fiction aesthetic? And what does this yearning to find long-dead Earthlings alive and well elsewhere in the universe say about us?

As a fan of, and occasional contributor to, exodinosaur lore, I’ve been percolating on these questions for well over a decade. One thing has become clear to me: Alien dinosaurs, while seemingly frivolous on the surface, are often potent projections of human fears and hopes about our place in space and time. So for all those seeking enlightenment via space dinosaurs, here’s a guide to the trope’s rich history.

Origins of the space dinosaur

The seeds of the modern “alien dinosaur” were planted in the late 19th century, as the first wave of dinosaur mania swept across North America and Europe. There was an intense public fixation on dinosaurs at this time, fueled by feuding American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, whose bombastic rivalry—which included bribery, theft, and other underhanded tricks—is now known as the Bone Wars.

From the 1870s to the 1890s, Cope and Marsh raced around the American West trying to out-dig each other in the quest to become the ultimate paleontologist. The pair identified over 130 new species of dinosaur before their rivalry drove them to ruin.

The remains of these extinct animals were carted off to natural history museums, where spectators gawked in awe and disbelief at their immense proportions and bizarre forms. But it wasn’t only their physical magnificence that entranced people—it was the paradigm shift they represented.

“In the late 19th century, people were working through tremendous social cataclysms and a wholesale scientific revolution that completely changed their understanding of the way the world worked on every level,” Zoë Lescaze, author of Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past , told me in a phone call.

Up until this period, the conventional Western wisdom was that Earth and all of its creatures were made by God during a very productive work week some 6,000 years ago. Dinosaurs were part of a flood of science that swept away that timeline and forced people to grapple with the incomprehensible age of the planet, and the life forms that existed on it before humans evolved.

“I think people were experiencing a fundamental destabilization of human importance, of the guarantee of our own survival, and of God’s benevolence, now that we learned that He could just wipe out creation,” Lescaze said. “It wasn’t exactly reassuring.”

“‘Space, the final frontier,’ is just the 20th century version of the American dream”

These revelations about past mass extinctions were concurrent with human-driven extinctions, like the annihilation of the passenger pigeon and the severe endangerment of bison. Even as people marveled at the idea that an entire group of animals could unceremoniously die off, as evidenced by fossils found on the American frontier, they were accelerating contemporary extinctions on the very same land.

Once the public had (somewhat) acclimated to the idea that the planet was not, in fact, served up fresh for human beings, a sense of Earthling rivalry with dinosaurs began to emerge. There was a public hunger to imagine clashes between dinosaurs and humans, with the dinos usually represented as monstrous brutes and the people equipped with sophisticated weapons and a righteous sense of superiority.

After all, what better way to justify Western exploration, technology, and conquest of nature—prevalent themes in late 19th century sci-fi—than with boss fights against literal incarnations of Earth’s brutal past?

Frontierosaurus

The connection between Wild West motifs and dinosaur iconography is explored in depth in The Last Dinosaur Book by W.J.T. Mitchell, a media historian at the University of Chicago. As Mitchell demonstrates, the Western environments from which dinosaurs were literally being exhumed doubled as grounds for their imaginative resurrection. This is shown beautifully by Bob Walters’ illustration “The Last Thunder Horse West of the Mississippi”—the cover art for Mitchell’s book, which depicts a sauropod rearing as riders close in on it in the badlands. From here, it is only one small conceptual step to dinosaurs in space.

“Aren’t the American frontier and outer space really the same thing when it comes to dinosaurs?” Mitchell wrote me in an email. “‘Space, the final frontier,’ is just the 20th century version of the American dream.”

To that point, consider that Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) depicted dinosaurs deep underground, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) found them hidden atop jungle plateaus, and Frank Mackenzie Saville’s Beyond the Great South Wall (1899) showed them popping up in Antarctica. It’s not all that surprising, then, that Gustavus W. Pope’s contemporary Journey to Venus (1895) went a step further and transplanted dinosaurs onto the titular alien planet.

“Along the shores, basking on the sands or wallowing in the miry fens, were huge land reptiles, the Iguanodons, Megalosaurs, and Dinosaurs,” Pope wrote in the book. “These were but the beginnings of the wonders displayed on this Primeval World.”

Pope’s novel was patient zero of the “Venutian dinosaur fallacy,” as science journalist and zoologist Ross Pomeroy described it, a phenomenon that was once so pervasive that astronomer Carl Sagan felt it was necessary to personally debunk it in 1980 on his PBS show Cosmos.

As Sagan explained, during the early-to-mid 20th century there was a widespread belief that Venus might be hiding secret dinosaurs in a balmy rainforest habitat under its cloud cover. (For context, this was before the Soviet Venera probes confirmed that our sister planet is, in fact, a gnarly hellscape.)

Much like the misidentified “canals” of Mars, Venutian dinosaurs were a result of more powerful telescopes that enabled astronomers to observe the finer features of our neighboring worlds. And where “Mars has canals” rapidly morphed into “hostile invading aliens, for sure” in the public imagination, “Venus has clouds” became “most definitely a dinosaur planet.”

Read more: The Demystification of Venus

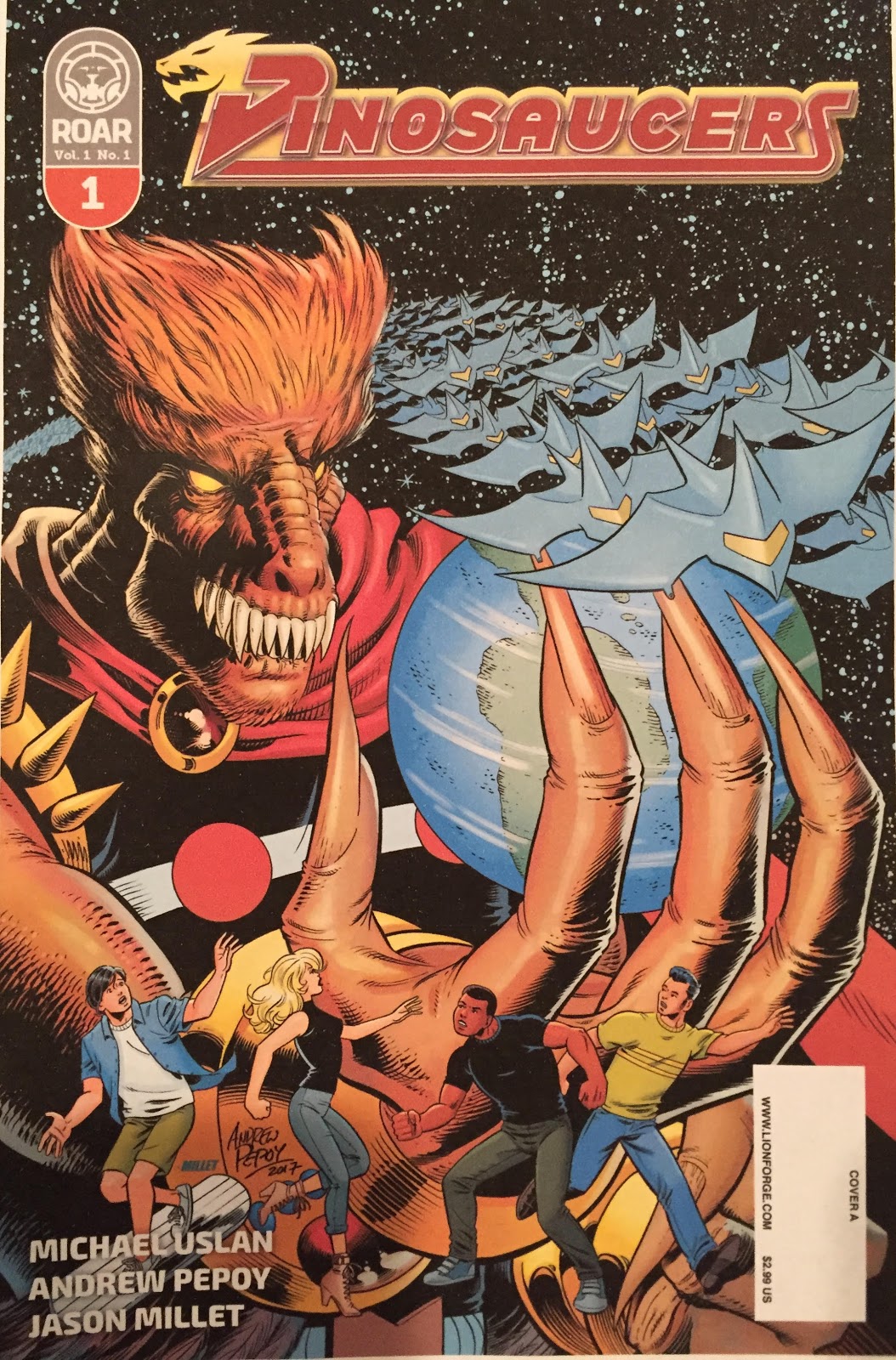

While astronomers cast doubt on the Venutian dinosaur theory long before the Venera landings, these imaginative riffs influenced many people. For producer Michael Uslan, creator of Dinosaucers, the demystification of these wild theories about Mars and Venus was central to his inspiration to remould the exodinosaur trope in fiction.

“I’m a Baby Boomer, so we are the last generation that wondered: ‘Who built the canals on Mars? What’s under the clouds of Venus?’” Uslan told me over the phone. “Is it all dinosaurs, in a steamy old world setting with volcanoes?”

“That was taken away from us by science,” he said, “so we needed a new sense of wonder, by doing science fiction while trying to keep pace with the facts of what’s happening with space travel, technology, and dinosaur discoveries.”

In this way, the space dinosaur genre has adapted to changing scientific and cultural landscapes for well over a century. In its early days, around the turn of the 20th century, the genre reflected a broader science fiction obsession with overpowering cultures and wildlife, paired with uneasy premonitions that unexplored land was rapidly running out.

These stories took pains to justify the bloodlust of human characters by making dinosaurs grotesque and violent. This characterization was underscored by contemporary paleoart depicting them as practically rabid.

“I think with the old pulp-type stuff, putting in a dinosaur as your monster was easy,” Pranas Naujokaitis, author of the Dinosaurs in Space children’s book series, told me in an email. “You’ve got this 20-foot tall demon lizard with a mouth full of banana-sized teeth. That’s scary and exciting. You put that image on a book cover, you are going to move some copies.”

Humans killing dinosaurs in epic battles resonated for audiences in a time when trophy hunting big game was a mainstream expression of machismo typified by President Theodore Roosevelt. But social attitudes shifted as animals from the frontier were brought into urban zoos for mass display, and conservation movements began to gain momentum in the 1940s and 1950s. The result of these trends was that fictional dinosaurs began to be caged and studied as often as they were killed for sport or dominance.

Jurassic Park… in space

King Kong (1933) exemplified the broader science fiction transition from survivalist battles against megafauna to their confinement for public spectacle. While the giant ape’s dinosaurian rivals on Skull Island escape his fate, many other fictional dinosaurs did not.

Writers began to imagine what it would be like to engage with captive animals from deep time (dinosaurs) and deep space (exodinosaurs) in the same way they interacted with exotic zoo animals.

Inevitably, Venutian dinosaurs popped up again in these narratives. In the March 1950 issue of Coronet magazine, a story entitled “Mr. Smith Goes to Venus” follows the Smith family as they take in the sights of the Venopolis Zoo, “one of the most fabulous attractions of Venus.”

The Venutian dinosaurs in this story are described as “dragon-like creatures” that made Mrs. Smith uncomfortable, as quoted by Matt Novak in Smithsonian. This narrative choice justified their captivity just as it had been used to justify slaughtering earlier versions of exodinosaurs. But a broader animal rights movement during the second half of the 20th century spilled over into the fictional exodinosaur world, changing these perceptions.

Take Anne McCaffrey’s 1984 book Dinosaur Planet Survivors, set on the fictional planet Ireta, which is populated by dinosaurian creatures. The exodinos are descendants of imported zoo creatures from Earth, and are depicted as intelligent. As a result, the story uses exodinosaurs to emphasize the human responsibility to respect and understand vulnerable animals.

The impact of wildlife advocacy can also be traced through stories about dinosaurs acquired from alien planets for display in Earth’s zoos, like author and filmmaker Donald Glut’s 1976 novel Spawn. Set in 2149, the novel follows an interplanetary mission to a planet called Erigon to collect alien dinosaur eggs that can be transported back to Earth to be incubated and raised in a preserve called Dino-World.

Fictional dinosaurs also began to migrate to space stations during the 1970s and 1980s, in stories that were, perhaps, inspired by the flights of the first long-duration orbital stations launched by the USSR and the US. In George R.R. Martin’s novella “The Plague Star” (part of the 1986 collection Tuf Voyaging), a ragtag group of salvagers stumble across an abandoned seedship called the Ark, which is packed with embryos of the most dangerous creatures on a variety of planets. Naturally, the Tyrannosaurus rex is Earth’s killer mascot.

In Martin’s story, the tyrannosaur is the only Earthling in the ship’s interplanetary menagerie of deathbringers. But sometimes you get all-dinosaur zoos on a space station, like in Robert Silverberg’s 1980 short story “Our Lady of the Sauropods.” The story takes place on Dino Island, a spaceship that houses genetically engineered dinosaurs made by humans. What began as a perfectly innocent attempt to resurrect dinosaurs for public amusement turns into mayhem when the ship’s operating system melts down.

Sound familiar? The story arguably laid the groundwork for the Jurassic Park trilogy—right down to a bloody rampage in San Diego. “After that unfortunate San Diego event with the tyrannosaur it became politically unfeasible [sic] to keep them anywhere on Earth,” the story’s narrator explains.

“Our Lady” is a kind of exodinosaur Rosetta Stone that weaves together the genre’s multiple modern threads—human technological arrogance, the ethics of bioengineering, and the allure of intelligent dinosaurs. These plot elements combine to persuade the story’s narrator to reach a sympathetic conclusion about exodinosaurian intelligence.

“We know just a shred of what the Mesozoic was really like. Just a slice, literally the bare bones,” the narrator says. “The passage of a hundred million years can obliterate all traces of civilization. Suppose they had language, poetry, mythology, philosophy? Love, dreams, aspirations?”

These ideas can be traced in part to the “dinosaur renaissance” of the 1960s which, like the earlier Bone Wars, was a time of immense discovery in paleontology. One of the most significant realizations during this flood of new science was that many dinosaurs were likely warm-blooded, quick animals, and some species may have been relatively clever.

“I think the old image of the dinosaurs as slow, stupid, and doomed to extinction is completely obsolete,” Mitchell told me. “The new model of the second half of the 20th century has much more respect for their agility, variety, and adaptability.”

These novel depictions are often accompanied by themes questioning human superiority to dinosaurs. At least the dinosaurs could blame an asteroid for their bad luck, Mitchell pointed out, whereas we may self-destruct with no outside help at all.

Dinosaucers

Perhaps the most colorful example of the rise of brainy dinosaurs was the animated show Dinosaucers, which ran for one season in 1987. The series stars a cast of anthropomorphic dinosaurs who can “dinovolve” into their ancestral dinosaur forms and who drive spaceships that are also shaped like dinosaurs.

Michael Uslan, the show’s co-creator and a prolific film and TV producer, first conceived of the idea while brainstorming concepts that might appeal to his then kindergarten-age son. “Dinosaurs in outer space are universal in terms of captivating kids,” Uslan told me. “So one morning, while I was shaving, I came up with the term ‘Dinosaucers’ and said: ‘Now that’s cool, what is it?’”

“Now it is our turn to rule the earth, and it looks as if we are creating the conditions for our own extinction“

Here’s what it is: The planet Reptilon orbits the Sun in the opposite position from Earth, rendering it undetectable to astronomers. Reptilon and Earth follow an exodinosaur tradition of being twin planets with the same sequence of evolutionary events, but unlike Earth, Reptilon was not hit by an asteroid 66 million years ago. On Reptilon, dinosaurs survived and developed into an intelligent species capable of interplanetary spaceflight. The show follows the battle between Reptilon’s bad Tyrannos and the good Dinosaucers, and a group of human kids, called the Secret Scouts, who get swept up in it.

Dinosaucers took many of the latent narratives surrounding exodinosaurs and cranked them up to literally cartoonish levels. The premise is built on the tantalizing idea of what dinosaurs might have become had they not been wiped out.

As paleontologist Darren Naish noted in Scientific American, this was a thought experiment that was already ascendent during the 1980s, amplified somewhat by Sagan’s ruminations about dinosaurs with advanced intelligence in The Dragons of Eden (1977). Paleontologist Dale Russell even partnered with sculptor Ron Séguin to visually represent a humanoid descendent of the relatively smart dinosaur Stenonychosaurus, premiering their “Dinosauroid” exhibit at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Ottawa in 1982.

Dinosaucers ran with this trend, giving its dinosaur characters many human attributes beyond their appearance—language, culture, agency, and technological ability were traits they possessed as well. It was one of the first mainstream portrayals of spacefaring dinosaurs as being significantly more advanced than humans, which expanded the exodinosaur narrative from “human versus red-toothed nature” to “human versus superior beings.”

“I think part of creators doing that is because using dinosaurs as the big bad guy or the mindless killing monster has been done,” said Naujokaitis, author of Dinosaurs In Space. “Audiences grow more sophisticated over time and want something different.”

In addition to this hunger for more imaginative dinosaur treatments, the shift toward hyper-intelligent space dinosaurs was also underpinned by cultural anxieties about human hubris—themes that would be integral to the Jurassic Park franchise.

“Extinction today has become a possibility, not just for some animals, but for us, the human species,” Mitchell said. “That is why dinosaurs are totem animals, symbols of our species’ being. They were the dominant animal group in their time, ‘ruling the earth.’ Now it is our turn to rule the earth, and it looks as if we are creating the conditions for our own extinction.”

Dinosaucers was a vector for these environmental issues at the time, and its themes still resonate with fans today. The show has garnered a cult following over the past three decades, partly due to a demand for the ultra-rare toys that were shelved after its cancellation, some of which are worth thousands of dollars. Writer Hans Geyer, who is currently working on a history of Dinosaucers, has tracked many of these valuable collectors items to locations all around the globe.

“People want them now because they can’t have them,” Geyer told me over the phone. “It’s really interesting to see that. Everybody loves the merchandise, whether it’s for nostalgia’s sake, or in some instances, the unattainable.”

Inspired by the renewed interest in the show, Uslan is currently working on a new comic book revival of Dinosaucers that, like the original concept, will aim to keep pace with scientific discoveries. For example, the imagery will show dinosaurs with feathers, and will emphasize climate change awareness, continuing in the tradition of the original show.

Once again, dinosaurs in space are proving to be more than a wacky meme showcasing childish fascinations—they’re a funhouse mirror for contemporary society.

“What the deep past and the distant future share is a fundamental foreignness for people living in the present,” Paleoart author Lescaze told me. “No one has ever seen prehistoric times and no one has seen the future, so we’re able to project our wildest fantasies and most imaginative whims onto both of those time periods. So while they might seem opposite and are on ends of the temporal spectrum, they share that quality.”

What will tomorrow’s space dinosaurs look like?

The exodinosaur in fiction has evolved from a symbol of the frontier, to a curiosity in zoos, to an intelligent stand-in for humans. And for all the commonalities between each version of the trope, everyone I spoke to seemed to take a different message away from it.

“Honestly, at the end of the day, I think it just comes down to how cool dinosaurs are,” Naujokaitis said. “It’s like a universal language. Almost everybody loves dinosaurs.”

Uslan links the appeal of exodinosaurs to a “sense of wonder.” Geyer told me that dinosaurs and space are “topics [that] stand the test of time.” “The knowledge that we can gain researching either topic just seems limitless,” he said.

Mitchell frames the trope through a more anthropocentric lens. “Why do human beings conjure up dinosaurs in space? For the same reasons we conjure up aliens,” he told me. “First, if the aliens are hostile, we have someone else to blame for our destruction; second, if they are friendly, they teach us how to mend our ways, and show us how to survive.”

And for Lescaze, there’s “an aspirational quality” to exodinosaurs. “If there can be dinosaurs in space, we can thrive there too,” she said. “Maybe, in the face of extinction and the profound terror that it engenders, there’s an element of hope. Perhaps dinosaurs are getting wrapped up in that.”

Ultimately, dinosaurs in space are an ever-evolving reflection of human life, mirroring our most wishful dreams and nightmarish fears. They are inherently silly and fantastical, yet they are also one of the most direct routes into our collective psyche. For that reason, to take the pulse of society, look to the exodinosaurs it has imagined.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter .

More

From VICE

-

Westend61/Getty Images -

Illustration by Reesa -

Screenshot: Midwest Games -

Screenshots: TE NET, FLAT28