For better or worse, we've grown accustomed to idea that we're under constant photo surveillance: there's a CCTV camera on every corner, a webcam on every computer, and a network of satellites capable of taking high resolution photos of the entire earth every day. But just 50 years ago, figuring out how to make high altitude photo surveillance happen was no small order.Indeed, the Air Force, ARPA (the Advanced Research Projects Agency, later renamed DARPA) and the CIA invested what would amount to several billion dollars today into the Corona program, the first US photo surveillance satellites launched throughout the 1960s. But based on the insane spy technologies that resulted from this program, the investment was well worth it.

Advertisement

The top-secret Corona program began in 1958 under the guise of a space exploration program called 'Discoverer'. After two years of technology development and a dozen unsuccessful launches, the Discoverer 13 capsule was recovered by the US on August 10, 1960. It was the first man-made object to be recovered from space (the Soviets would send up two dogs and successfully recover them just a week and a half later) and marked the beginning of the age of space-based surveillance.

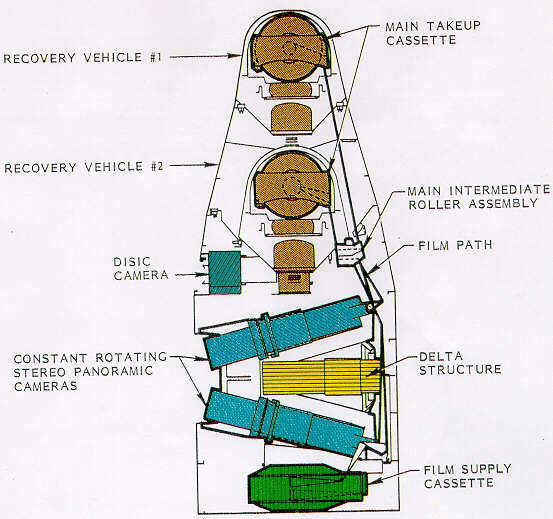

Beginning with Discoverer 14, each Corona program satellite carried increasingly sophisticated camera equipment on-board. They used special 70mm film made by Kodak (for the sake of comparison, civilian cameras typically use 35mm film) which allowed for wide and high resolution shots. Early Corona satellites carried about a mile and a half of film for each of the two cameras on board, but by the fifth generation of satellites this had doubled to about 3 miles of film per camera. The first satellites would take photos constantly, but later versions could be manipulated by radio to go to sleep and resume taking pictures at a later date.The cameras used were specially designed by the defense contractor Itek, which specialized in reconnaissance systems. These cameras were mid-range telephoto (610mm focal-length) with a 7-inch triplet lens (a lens that is actually a composite of three lenses to correct for distortion). The entire cameras were initially about 5 feet long, but this size was later increased to 9 feet.

Advertisement

To calibrate the cameras from space, the Air Force made a giant grid of concrete crosses in the desert outside of Phoenix, Arizona. These 267 crosses, each about 60 feet in diameter, are a mile apart from one another down to the millimeter. They were used as "ground truth" targets since the size and distance between each cross was known and could be used to determine the accuracy of photographs taken elsewhere on Earth.

In short, the photographic equipment on-board the Corona satellites was nothing to bat an eye at. Initially, these cameras were only able to resolve images on the ground down to a diameter of 40 feet from an orbit of 100 miles up (the same as the International Space Station), but later generations of Corona satellites reduced this to objects just 5 feet in diameter—which is nearly on par with satellites used today.The problem, of course, was how to recover the precious photographic intelligence (mostly of Chinese and Soviet projects) that was on board these satellites after they had used up all their film.

The solution was to jettison the two re-entry capsules for each camera (appropriately known as the "film buckets"). These each came equipped with a heat shield which would be dropped after the film bucket reached 60,000 feet, at which point a parachute would be deployed. The film bucket would continue its descent to Earth until about 15,000 feet, at which point a plane would fly by and scoop the descending capsule out of the air. While such a recovery technique might seem delightfully analog today, China was using film buckets as recently as 2005 for their surveillance satellites.This rescue maneuver didn't always work out as planned.

As might be expected, this rescue maneuver didn't always work out as planned. In one particularly notable instance in 1964, some Venezuelan farmers happened upon a Corona reentry capsule, prompting the Air Force to stop labeling the capsules as 'SECRET' and instead labeling them with a notice written in 8 languages that advertised a reward if the capsule was returned to the US. To improve on this security flaw, the US intelligence community briefly flirted with an alternative to Corona called SAMOS. These satellites would develop photos in orbit, scan them and then transmit the image back to Earth via with radio telemetry. Although this prefigured modern satellite imagery, the tech used at the time was unable to process many photos each day, so the program was abandoned.Although the Corona program was discontinued in 1972, due to improvements in technology and changing national security prerogatives, it wasn't until 1995 that President Clinton ordered the details of the Corona program declassified. Today these images are used to study ancient sites and traveling routes in the Middle East, and to remind us of our surveillance state's humble origins.Motherboard is nominated for three Webby Awards for Best Science YouTube Channel , Best Drama , Best Tech/Science Podcast . Please vote for us!