In the early 1980s, the science fiction sub-genre of cyberpunk seemed like the voice of a generation. Visceral, topical, and nihilistic, cyberpunk aimed to be to the 21st century what punk rock was to the 20th. Today, however, despite our exponentially increased intimacy with technology, it’s more immediately associated with Max Headroom than maximum cultural dissent. Yesterday I asked myself about the fate of cyberpunk; for today, I put the question to ten science-fictional thinkers, including a coterie of the genre’s parents: What happened to cyberpunk?William Gibson is the author of Neuromancer. See an interview with him here.Cyberpunk today is a standard Pantone shade in pop culture. You know it when you see it.Rudy Rucker is the Philip K. Dick award-winning author of the “Ware” Tetralogy, a computer scientist-cum-philosopher, and one of the founders of cyberpunk as we know it. He presently edits the science fiction webzine Flurb.Although cyberpunk is now viewed as a successful subgenre of SF, it was indeed controversial when we started. But that’s the way we wanted it. All of us had, and still have, an implacable and unrelenting desire to shatter the limits of consensus reality. If nobody’s pissed off, you’re not trying hard enough. I’ll never stop being a cyberpunk. We started writing cyberpunk because we had a really strong discontent with the status quo in science fiction, and with the state of human society at large. Conventional thinkers even now aren’t yet comfortable with the notion that digital reality and mental reality are points on a continuum. Another cyberpunk teaching that’s not so widely known is that digital things can be squishy, funky, and smooth. Like robots that are made of soft, flickering plastic that’s infested with smelly mold.—Charlie Stross is the Locus and Hugo-winning author of Accelerando and Singularity Sky.Cyberpunk is roadkill on the information superhighway of the 1990s. No more and no less. Bruce Sterling more or less declared it dead in 1985, and he was right; as a movement within SF it had done its job by then. The world we live in is the future of the 1980s cyberpunks.This is not necessarily a good thing.Benjamin Rosenbaum is a computer programmer and author of science-fiction short stories that have been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Harper’s and McSweeney’s.Cyberpunk is the genre that gave us the lingusitic back-formation “-punk”, meaning, “genre which messes around with”; but unlike its successor “-punk” genres (cypher, steam, etc) cyberpunk was actually related to punk music: raw, gritty, anarchic, rebellious, disgusted with empty conventions and proprieties, obsessed (on a certain level) with authenticity. Just as the innovation of the early rock and rollers and the British Invasion had degenerated (from the punk rock perspective) into the bloated pretensions, the light shows and orchestral follies, of 70s dinosaur bands, so too the authentic speculation of Golden Age SF had degenerated into a series of tropes — FTL galactic empires, humanoid aliens, nefarious AIs, loyal robots — which represented (to the cyberpunks), not thinking about the future, but merely using it as a set dressing. The real future was happening all around them, in waves of privatization and deregulation and postindustrialism and the end of jobs-for-life, in the Apple ][s and 7800 baud modems and BBSs… and the dinosaur bands of SF were ignoring it in favor of the light shows of interstellar colonialist adventure.

Now, of course, cyberpunk itself has suffered the same fate. Noir antiheroes in mirrorshades and black trenchcoats hacking into corporate and government systems, the internet envisioned as an immersive (even physically invasive) world — these are no longer daring speculations: they are Hollywood staples. The internet is here and much of its nomenclature derives from cyberpunk’s visions; the world is full of the real-life successors of Case and Hiro — network manipulators with flexible moralities, independent streaks, and a willingness to hide in the nooks and crannies of the Matrix — from Nigerian scammers to Julian Assange. But of course, now that they’re real, they’re harder to imagine as Keanu Reeves saving the day.

This produces a bifurcation. The tropes and standard moves of cyberpunk are static; the spirit moves on. No true cyberpunk, in 2012, would be caught dead writing “cyberpunk”, any more than a 1980 cyberpunk would have written trope-y planetary romance. The creators of cyberpunk are mostly still active, writing all manner of things, their restless spirit of inquiry still intact. They handed off their famous tropes to the decidedly un-punk factories of standard fiction, and asked new questions.-One of the few women associated with the early cyberpunk movement, Pat Cadigan is the author of Synners and Fools, both awarded the Arthur C. Clarke award.Nothing “happened,” it’s just more evenly distributed now. John Shirley is a seminal cyberpunk, author of the Song Called Youth trilogy, City Come A-Walkin’, and Black Glass. He is also known for his avant-garde horror novels and stories; critic Larry McCaffery called him a “post-modern Edgar Allen Poe.” He has collaborated with fellow cyberpunks William Gibson, Rudy Rucker, and Bruce Sterling.

There is a new collection of Cyberpunk stories coming from Underland Press, with me and Gibson etc… my cyberpunk novel Black Glass came out just a few years ago. But on the whole what happened to it, is that it was appropriated, co-opted, by other people, into other forms…cannibalized…I’ve done a redrafting and updating of my cyberpunk trilogy A Song Called Youth, in a single volume… And that is brand new and people are paying attention to it.-Douglas Rushkoff is a writer and theorist strongly affiliated with the early cyberpunk movement, and author of ten books on media and technology, including Program or Be Programmed and Cyberia. He teaches in the Media Studies department at The New School University. See his Motherboard interview here.For most people, it was surrendered to the cloud. For those who understand, it stayed on their hard drives.Neal Stephenson is the author of Snow Crash, Cryptonomicon, and The Diamond Age, all classics of speculative fiction.

It evolved into birds.

John Shirley is a seminal cyberpunk, author of the Song Called Youth trilogy, City Come A-Walkin’, and Black Glass. He is also known for his avant-garde horror novels and stories; critic Larry McCaffery called him a “post-modern Edgar Allen Poe.” He has collaborated with fellow cyberpunks William Gibson, Rudy Rucker, and Bruce Sterling.

There is a new collection of Cyberpunk stories coming from Underland Press, with me and Gibson etc… my cyberpunk novel Black Glass came out just a few years ago. But on the whole what happened to it, is that it was appropriated, co-opted, by other people, into other forms…cannibalized…I’ve done a redrafting and updating of my cyberpunk trilogy A Song Called Youth, in a single volume… And that is brand new and people are paying attention to it.-Douglas Rushkoff is a writer and theorist strongly affiliated with the early cyberpunk movement, and author of ten books on media and technology, including Program or Be Programmed and Cyberia. He teaches in the Media Studies department at The New School University. See his Motherboard interview here.For most people, it was surrendered to the cloud. For those who understand, it stayed on their hard drives.Neal Stephenson is the author of Snow Crash, Cryptonomicon, and The Diamond Age, all classics of speculative fiction.

It evolved into birds. Cory Doctorow is a blogger, journalist, and award-winning science fiction author. Co-editor of the blog Boing Boing, he is a global advocate for the liberalization of copyright laws.

Funny thing about the OG cyberpunks is that they all talk slowly. Gibson, Sterling, Cadigan, Rucker, Womack — southerners and midwesterners, all with rather magisterial delivery, all slow. All the c-punky/post-c-punky writers I know — me, Stross, Beukes, Rosenbaum — talk like auctioneers, rattling at high speed like a rickety rollercoaster on the downhill side.

Make of that what you will.-.Bruce Bethke is the author of Headcrash and “Cyberpunk,” the short story that first gave a name to the movement.As a literary form, what happened was what happens to every successful new thing in any branch of pop culture. Cyberpunk fiction went from being something unexpected, fresh, and original, to being a trendy fashion statement; to being a repeatable commercial formula; to being a hoary trope, complete with a set of stylistic markers and time-honored forms to which obeisance must be paid if one is to write True Cyberpunk. Frankly, as the editor of Stupefying Stories, it cracks me up every time I read a cover letter from some eager young writer gushing about how I of all people should appreciate his or her new cyberpunk story. Yes, there are some bright new talents out there writing some great new cyberpunk-style stories that would be absolutely perfect —In the pages of Asimov’s, in 1985!But out here in the larger world time has moved on, and those kinds of stories look as quaint now as did Chesley Bonestell’s beautiful 1950s spaceship art after Apollo landed on the Moon. The cyberpunk trope, as a literary form, is still stuck firmly in the 1980s, with no hope of ever breaking free.

Cory Doctorow is a blogger, journalist, and award-winning science fiction author. Co-editor of the blog Boing Boing, he is a global advocate for the liberalization of copyright laws.

Funny thing about the OG cyberpunks is that they all talk slowly. Gibson, Sterling, Cadigan, Rucker, Womack — southerners and midwesterners, all with rather magisterial delivery, all slow. All the c-punky/post-c-punky writers I know — me, Stross, Beukes, Rosenbaum — talk like auctioneers, rattling at high speed like a rickety rollercoaster on the downhill side.

Make of that what you will.-.Bruce Bethke is the author of Headcrash and “Cyberpunk,” the short story that first gave a name to the movement.As a literary form, what happened was what happens to every successful new thing in any branch of pop culture. Cyberpunk fiction went from being something unexpected, fresh, and original, to being a trendy fashion statement; to being a repeatable commercial formula; to being a hoary trope, complete with a set of stylistic markers and time-honored forms to which obeisance must be paid if one is to write True Cyberpunk. Frankly, as the editor of Stupefying Stories, it cracks me up every time I read a cover letter from some eager young writer gushing about how I of all people should appreciate his or her new cyberpunk story. Yes, there are some bright new talents out there writing some great new cyberpunk-style stories that would be absolutely perfect —In the pages of Asimov’s, in 1985!But out here in the larger world time has moved on, and those kinds of stories look as quaint now as did Chesley Bonestell’s beautiful 1950s spaceship art after Apollo landed on the Moon. The cyberpunk trope, as a literary form, is still stuck firmly in the 1980s, with no hope of ever breaking free.

But the ideas originally behind that trope — now that’s the cool part. My friends who work in aerospace tell me the old guys who built the industry all grew up reading Heinlein and Clarke, and went into aerospace to turn those crazy things they read as kids into practical realities as adults. Well, I work in supercomputing, and I can assure you that this industry is full of young geniuses who grew up reading Gibson, Vinge, and Rucker — and yes, me — and they went into this field to do the same thing.

We don’t quite live in the world that cyberpunk fiction predicted. But we live in the world that the kids who grew up reading cyberpunk fiction built, and that is a very cool thing indeed.Jack Womack is the Philip K. Dick award-winning author of the Dryco series.

Last time I saw cyberpunk I threw 25 cents in its hat.

But the ideas originally behind that trope — now that’s the cool part. My friends who work in aerospace tell me the old guys who built the industry all grew up reading Heinlein and Clarke, and went into aerospace to turn those crazy things they read as kids into practical realities as adults. Well, I work in supercomputing, and I can assure you that this industry is full of young geniuses who grew up reading Gibson, Vinge, and Rucker — and yes, me — and they went into this field to do the same thing.

We don’t quite live in the world that cyberpunk fiction predicted. But we live in the world that the kids who grew up reading cyberpunk fiction built, and that is a very cool thing indeed.Jack Womack is the Philip K. Dick award-winning author of the Dryco series.

Last time I saw cyberpunk I threw 25 cents in its hat.

Advertisement

William Gibson

Rudy Rucker

Cyberpunk is roadkill on the information superhighway of the 1990s.

Charlie Stross:

Advertisement

Benjamin Rosenbaum:

Advertisement

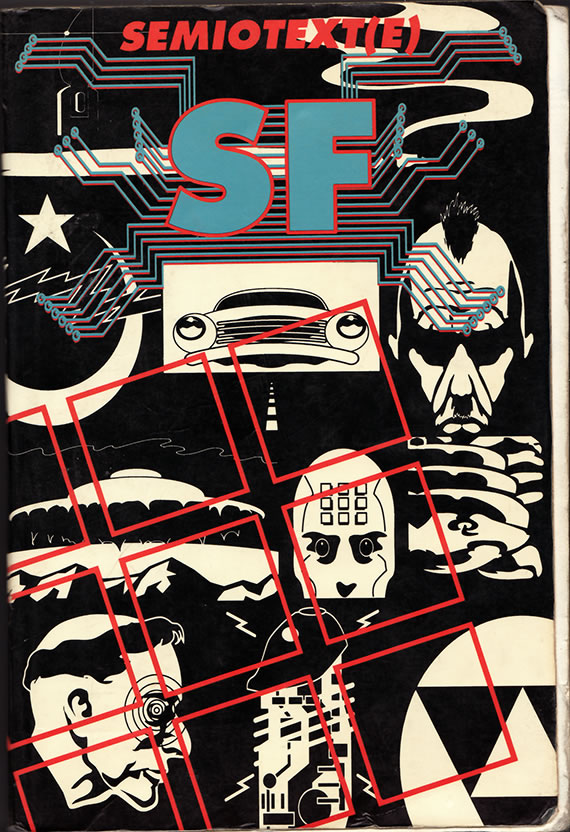

Semiotext(e), SF issue, 1991

If nobody’s pissed off, you’re not trying hard enough. I’ll never stop being a cyberpunk.

Pat Cadigan:

Advertisement

T-shirt from zipporalux available at Largetosti

John Shirley:

The world is full of network manipulators with flexible moralities, independent streaks, and a willingness to hide in the nooks and crannies of the Matrix. But of course, now that they’re real, they’re harder to imagine as Keanu Reeves saving the day.

Douglas Rushkoff:

Advertisement

Neal Stephenson:

Illustration by Julien Pacaud

Cory Doctorow:

The old guys who built the aerospace industry all grew up reading Heinlein and Clarke, and went into it to turn those crazy things they read as kids into practical realities as adults.

Bruce Bethke:

Advertisement