Our ideas about gender, race, and countless other unconsciously held beliefs affect the way we frame diseases and disorders. But sometimes they create those diseases too.In 1859, it was believed that a quarter of women suffered from hysteria. Many required constant care from physicians – pelvic massage, water massage, bed rest, and expensive spa treatments — in order to "manage" their symptoms. Hysteria was considered a legitimate disease by the medical community and was studied the world over by preeminent psychologists, including Freud. How did this disease, which purportedly affected so many women and was studied extensively by some of the greatest medical minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – and which is now the focus of two new Hollywood movies – manage to disappear?

In the mid-nineteenth century, a sprawling seventy-five-page document cataloguing symptoms of the disorder was considered incomplete. What it did include was a litany of complaints that most women (and men for that matter) experience at some point: fatigue, weakness, nervousness, sexual dissatisfaction, insomnia, and a tendency to cause trouble. Though more extreme manifestations of the disease — fits of screaming and howling, catatonia, and contortion of the limbs — did occur, they were lumped in with seemingly benign symptoms under this umbrella diagnosis.Thus, any woman who was dissatisfied with her life – which wouldn't have been uncommon in the sexually repressed Victorian-era – would have likely received a "hysterical" diagnosis. Tell anyone that they're weak and sick enough times and they'll likely begin to believe that they're weak and sick.Hysteria has its beginnings in ancient Greek culture. Though the term "hysteria," derived from the Greek word for uterus, is commonly attributed to Hippocrates, in fact, he merely developed theories concerning female anatomy that were later associated with it. He was convinced that the irregular movement of blood from the uterus to the brain was responsible for various feminine fits, outbursts, and discomfort. The solution of his contemporaries? Get pregnant. This "moistened" the womb, thus restoring balance to a woman's poor, dried-up reproductive organs.Hysteria remained long after the Greeks, but wasn't until the mid-nineteenth century that diagnoses really got booming. Thanks to oppressive Victorian sexual mores and the Industrial Revolution, well-to-do women were stuck at home with little social contact and even fewer sexual outlets. It would have been inappropriate to complain about sexual dissatisfaction; instead, a medical issue with vague symptoms like hysteria was preferable.Hysterics were a lucrative market for physicians: they didn't die and there was no cure. Patients just kept paying for treatments indefinitely. It's not hard to see why the medical community enjoyed it so much.

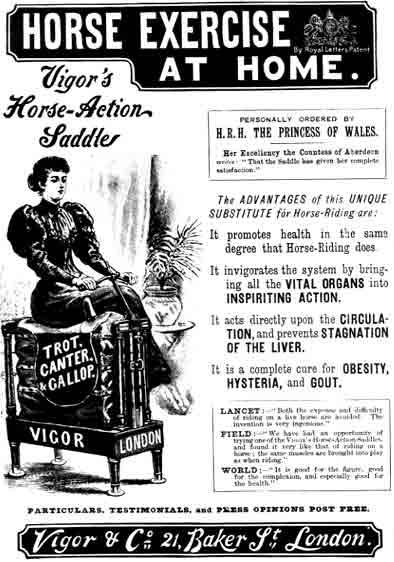

Interestingly, the loosely associated symptoms of hysteria evoke the current medical definition of Female Sexual Dysfunction, another nebulous condition of dissatisfaction afflicting up to 43 percent of women. FSD is another disorder with no clear cure; it, like hysteria, often requires consistent medical intervention to "manage" symptoms, a lucrative venture for involved doctors and the pharmaceutical industry. (I’ve previously talked about FSD with Liz Canner, the filmmaker behind Orgasm, Inc.)When these women began presenting hysterical symptoms to their doctors, they employed the tried-and-true method of "pelvic massage," essentially a vaginal massage resulting in orgasm, to cure them of their blues. By 1870, the invention of the mechanical, hand-crank vibrator allowed physicians to "treat" hysteria without the over exertion of their digits.The electric vibrator soon followed, and doctors would often see women weekly to administer treatment. By the early twentieth century, vibrators were available on the consumer market, and they’re getting more interesting all the time. They appeared nine years before the electric vacuum cleaner, if that gives you any idea of the demand for "paroxysms."It wasn't until Sigmund Freud published a series of articles on hysteria that it began to be understood as a mental, rather than strictly physical, condition. In "Studien uber Hysterie," often cited as the founding paper on psychoanalysis, Breuer and Freud recount their success in treating hysterical patients using the technique of free association psychoanalysis. The focus had shifted from feminine physical fragility to feminine mental instability.Hysteria existed as a commonly diagnosed – and still a seemingly legitimate medical complaint – until into the twentieth century. Eventually, however, hysteria fell out of fashion. Greater understanding of neurological disorders like epilepsy led to the reclassification of symptoms that would once have been deemed hysterical.

Hysteria was once the domain of upper class women, those who had the means to undertake costly medical treatments, but the invention of the home vibrator had dramatically reduced the cost of the "cure" so practitioners were less invested in promoting hysteria as a disease. And as greater awareness of the disease led to more middle and lower class women diagnosed with hysteria, the disorder simply began to fall out of fashion. In 1952 the American Psychiatrist Association removed hysteria from its list of recognized diseases. Now, no one has it.Yet, there are echoes of hysteria in our current understanding of disease. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome afflicts four times as many women as men. FSD, much like hysteria, frames women's sexual dissatisfaction as a function of physical and mental weakness. And there's even Restless Leg Syndrome, "a neurological disorder characterized by throbbing, pulling, creeping, or other unpleasant sensations in the legs and an uncontrollable, and sometimes overwhelming, urge to move them," clinical depression, and anxiety disorders, all of which affect twice as many women as men.This isn’t to cast aspersion on vibrators; they’re great. But have the conditions that gave rise to them really disappeared, or have we fractured “hysteria” into countless smaller, more manageable conditions? One thing seems clear: tell women they're mentally and physically weaker for long enough and they believe it. And if there's an industry profiting from their treatment, especially a medical one, there's little incentive for any one to question whether or not their "disease" is real.This piece originally appeared Nov. 30, 2011.

Advertisement

This home cure also works for obesity.

Advertisement

Don’t worry, he’s a doctor.

Advertisement