A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium , a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.You know something you can't get through the internet's wires, at least not on its own? Food.We've been working on it for years, but no, we're not at the point where we can deliver nourishment directly via the series of tubes.But food has always been something of a means to an end—a way of driving the internet forward, making it something people would actually like to use. Fact is, if you're trying to get people to try something new, looking at Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and fulfilling one of the listed needs—the lower down the hierarchy, the better—is a good way to ensure success. (And food is at the bottom.)

Advertisement

The Internet of Food, of course, starts with a Coke machine. It always does.

Why the "Internet Coke Machine" is actually more innovative than it soundsWhen I mentioned to my wife that one of the internet's earliest phenomena involved a Coke machine that had its own website, she scoffed—because the idea, at its root, sounds absurd and useless.It's an innovation that sounds absurdly pedestrian when you can convince Alexa to buy you a $170 dollhouse and four pounds of cookies by accident.But as it turns out, it's all about the use case.Carnegie Mellon University, which long managed this shining example of Maslow's Hierarchy in action, came up with the idea because the computer science department had been moved away from the machine, and the thirsty programmers needed a way to confirm that there were beverages in the machine—and, more importantly, that they were actually cold. From CMU's history page for the device:

Why the "Internet Coke Machine" is actually more innovative than it soundsWhen I mentioned to my wife that one of the internet's earliest phenomena involved a Coke machine that had its own website, she scoffed—because the idea, at its root, sounds absurd and useless.It's an innovation that sounds absurdly pedestrian when you can convince Alexa to buy you a $170 dollhouse and four pounds of cookies by accident.But as it turns out, it's all about the use case.Carnegie Mellon University, which long managed this shining example of Maslow's Hierarchy in action, came up with the idea because the computer science department had been moved away from the machine, and the thirsty programmers needed a way to confirm that there were beverages in the machine—and, more importantly, that they were actually cold. From CMU's history page for the device:

In other words, this device may have been the first "Internet of Things" device, and it was even more novel once it had been connected to the web in 1993.They installed micro-switches in the Coke machine to sense how many bottles were present in each of its six columns of bottles. The switches were hooked up to CMUA, the PDP-10 that was then the main departmental computer. A server program was written to keep tabs on the Coke machine's state, including how long each bottle had been in the machine.

Advertisement

There were a lot of imitators over the years, but it turns out that the soda companies are doing something pretty similar these days.In 2015, Bizjournals reported that vending machine companies, including Coca-Cola, have started to rely on internet-connected platforms. This is good, notes reporter Efrat Kasznik, because it allows beverage and food distribution companies to refill the machines so they're never empty, as well as tighten supply chains. Suddenly, a staid business becomes a big data business.Take Coca-Cola's Freestyle machine. While it's better known as a fancy way to mix Sprite with Mello Yellow Zero at your local Boloco, it's a prime example of this concept in action:Supplying the machines with network connectivity allows Coke to identify each individual machine, track inventory stock levels, conduct real time test marketing, and probably most importantly: track trends and drinking preference and adjust the selections accordingly. More than 2,000 Freestyle machines are currently deployed in fast food locations throughout the U.S. and the U.K.In other words, a Coke Freestyle machine is an Internet Coke Machine on steroids, and you should treat it as such going forward.

Of course, if you closely followed the internet's formative food years, you'll know that Coke machines weren't the only early way food interacted with wires. Early on, food fans saw a lot of potential for the web to redefine delivery.That said, if you looked at Pizza Hut's early attempt at delivering pizzas based on technology—a platform called PizzaNet—it might have looked like a failure.

The story of the first company to do large-scale online food delivery reads like a parody of a dot-com startup

Advertisement

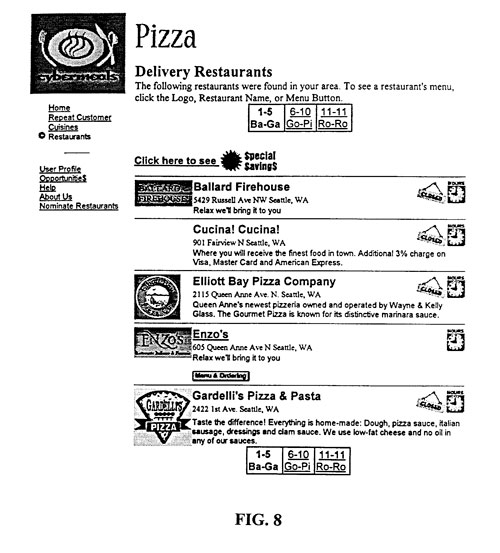

Early on, Pizza Hut generally sold fewer than 10 pies each week through its initial experiment in online ordering. Part of the issue was the newness of the technology; part of it was scale: The experiment was limited to the residents of Santa Cruz, California at the time, in part because the developer of the pizza-delivery technology was SCO.(Side note: If you followed the open-source scene in the early 21st century, you might have shuddered at the mention of SCO due to a certain long-running legal battle, but that was a completely different company that bought the name.)Jonathan Cohen, a former SCO marketing person who was dead-set against the PizzaNet idea but now eats his Stuffed Crust Pizza with crow, wrote a great recollection about the saga last year.But while Pizza Hut had the basic idea of delivering pizza via the internet, it was another company that did much the early legwork to make the concept widespread.And that startup's inspiration was sort of depressing, considering it was an internet-based startup. Tim Glass, a guy from Seattle, had seen the 1995 film The Net, the Sandra Bullock vehicle in which a bunch of terrible internet-related things happen.One of those internet-related things involved the ordering of a pizza through a computer—something most certainly inspired by the Pizza Hut test a year prior.But when Glass looked around for a real-world example of the idea, he couldn't find one. So he created his own, starting up a company called CyberSlice in 1996.

Advertisement

"Millions of people order pizza every day and we're about to change that whole experience," Glass explained in a 1996 news release. "Have you ever flipped through the phone book for your favorite pizzeria only to find it's closed, doesn't deliver or the staff is too hurried to discuss the menu or specials? CyberSlice takes the guesswork out, giving consumers more choice and value than traditional phone ordering. We took a simple idea and built an entertaining and enjoyable Web destination, while staying focused on customer service and satisfaction."This whole state of affairs was more complicated than it sounds. Remember, Google Maps didn't exist then, so the company had to rely on the vanguard at the time, which was MapQuest. Like Pets.com just a couple years later, the company had to build out a lot of its own technology.

On the plus side, because they were first, they were able to patent the idea of delivering food ordered on the internet, which is probably a very valuable patent these days.The company, in a pretty astute bit of marketing, used WebObjects, the NeXT Software-created online platform, and built one of the first sophisticated pieces of software using that tool. That meant it got free promotion from NeXT upon launch. Steve Jobs literally was CyberSlice's first customer."NeXT is excited to provide the enabling technology to CyberSlice, which combines fun with an innovative business concept," Jobs said at the time. "The success of CyberSlice shows the versatility of WebObjects in creating and deploying consumer web applications that are both sophisticated and original."

Advertisement

(They got in just in time, by the way—Apple acquired NeXT just 17 days after Jobs was quoted in that press release.)That stroke of good luck quickly turned out to be a mess, because of a particularly bad idea: According to Newsweek, the company, soon renamed Cybermeals, spent $54 million on advertising—on four major web portals over a four-year period. This was costly and poorly-considered, because web advertising wasn't very good at the time, and not every market had the company's service.

Eventually, the company had to revamp its approach entirely, which may have made things even worse. In 1998, a venture capital firm replaced the firm's entire leadership team in exchange for $10 million in capital, and brought in a former Disney exec, Rich Frank. By early 1999, CyberMeals had been renamed Food.com. The company blew through $20 million in capital in 1998 alone.Soon enough, it had raised even more money—a fresh $80 million round—from some unusually big-name backers: McDonald's, Kraft, TV Guide, and Blockbuster. (The latter, by the way, tried to sell the idea of combining restaurant delivery and movie rentals.)At the same time, it expanded its mission to be, as a March 2000 press release put it, "the nation's dining network, offering consumers a single destination for anything related to food—and accessed from a variety of devices from personal computers to wireless handhelds and televisions."

Advertisement

You could technically say that Food.com has done that. Literally, if you go to the website right now, it is a clearinghouse of all things food. But it only became that because the Food Network, quite literally "the nation's dining network," bought it in 2003.So here's a company that was founded based on a good idea in a bad movie, whose first customer was Steve Jobs, whose CEO used to work for Disney, and counted McDonald's and Blockbuster among its investors. It blew through tens of millions of dollars like nothing. And it was bought out by the Food Network essentially because it had a good domain.(Read that last paragraph over and consider whether, if we were playing Mad Libs, if you'd ever come up with anything close to that list.)These days, of course, food and the internet work together pretty neatly. Case in point: Back in 2014, GrubHub Inc. saw its stock surge by 31 percent during its first day on the market.The company, which merged with Seamless in 2013, effectively nailed down the model in ways that Food.com never could. (In case you were wondering: Neither Grubhub nor Seamless came to life because their respective owners saw a Sandra Bullock movie.)The stock price has had ups and downs, but ultimately the company highlights the fact that the Food.com model was ultimately quite good—it just needed a more efficient company to pull it off.

So I'm going to fully admit that I have a bright orange Chrome Industries bag, and I love it, but I don't do anything that could be described as "messaging" with it, unless you consider what I'm doing now with my laptop in that way.

So I'm going to fully admit that I have a bright orange Chrome Industries bag, and I love it, but I don't do anything that could be described as "messaging" with it, unless you consider what I'm doing now with my laptop in that way.

Advertisement

The only thing that could make it better, really, is if the messenger bag was a Kozmo.com bag. Chrome Industries got its start in 1995, and just a couple of years later, its bags were converted into the startup's main promotional tool.

Kozmo.com was perhaps the early web's most inventive delivery service. It could get you pretty much anything you wanted in a relatively short period of time, and often, it showed up in an orange Chrome bag. The company, like most other dot-coms of the time, went belly-up in short order as the stock market went to hell. But Chrome is still with us and still doing well—despite the fact that its bags are built to last for-friggin'-ever. (Which means that I'll be 80 and still carrying around an awesome orange messenger bag. Deal with it.)And because they last for-friggin'-ever, Kozmo bags occasionally show up on sites like eBay for auction. Sample line from an expired auction from 2013: "The bag is super-tough, can hold three New York style pizzas, and is impervious to weather."The Wired Twitter account even referenced the thing in a joke one time.I don't know about you guys, but I suddenly feel compelled to slap a Kozmo logo on my bag just to throw people off. Just don't expect me to deliver you a pint of ice cream.