Bacterial colonies have the ability to communicate with each other over relatively long distances via a series of electrical zaps—and can actually use these signals to recruit other bugs to their massive slime “cities,” San Diego researchers say.

Figuring out how these tiny creatures exchange information could be key in understanding our own microbiomes, and give us new ways to deal with the impending antibiotic resistance crisis. Beyond that, it’s another interesting window into bacterial life.

Videos by VICE

In a similar fashion to neurons, colonies called “biofilms” use potassium ion channels to regulate social interactions between bacteria in these massive groupings, and those nearby. This includes resolving conflicts, as this same team of researchers has previously shown.

Biofilms form when microorganisms collect on a surface, like a scummy rock or the bathtub you keep meaning to clean. They can be gatherings of one or more species of bacteria or other microbes, and are generally referred to even by researchers by their colloquial name: slime.

Video: Suel Lab @ UCSD/Youtube

“They live in dense cities just like we do,” Gürol Süel, Associate Director of the San Diego Center for Systems Biology, and lead author of the new paper, published Thursday in Cell, told Motherboard during a telephone interview. “The environment is basically other bacteria and they’re very densely packed in these biofilms.”

Read More: I Skipped Showering for Two Weeks and Bathed in Bacteria Instead

Süel’s previous work was to determine how these collections of creatures—which can have populations numbering in the millions—cooperate to collect food and make sure that creatures on the inside of the biofilm don’t end up starving, if the guys at the edge eat up all the nutrients available.

The paper describes a newly discovered mechanism where bacteria use the same communication channels to reach out and tell free-floating organisms that there’s safe haven where they can live and eat nearby.

What makes it even more striking is it doesn’t matter what kind of bacteria is on the receiving end of the message. “We show that this recruitment is not species-specific, but it’s species independent in the sense that it works also for very different species,” said Süel.

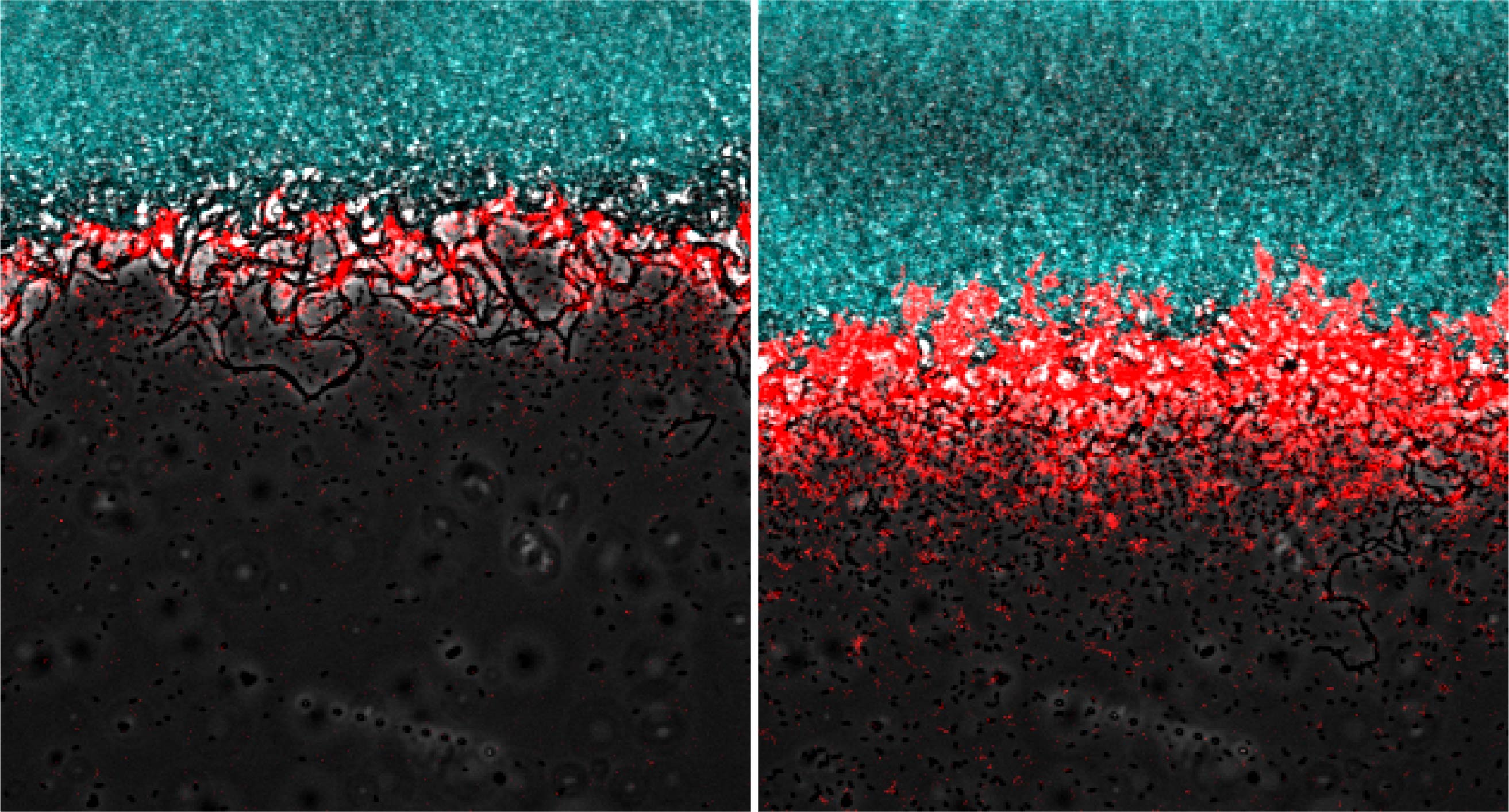

Electrical messages sent by biofilms (in green, at left) recruit new members (in red, at right) to the microbial community. Image: Suel Lab/UC San Diego

Many biologists now theorize that the three pounds of gut bacteria that live inside of us play a huge part in a number of bodily functions—including our mental faculties. Imagine if this new discovery could be used as an interface for us to control our internal ecosystems, a possibility raised by Süel and others.

“In the future it might be possible to sort of use some kind of electrical-based biomedical approach to control the behavior of bacterial communities that might be relevant for human health,” said Süel.

This results could also open up new fronts in the war against antibiotic resistance, as biofilms are very difficult to kill.

“Just discovering that these bacteria can communicate electrically to coordinate not only their behavior within biofilm,” said Süel. “But now we’re showing it also affects the behavior of bacteria at a distance. What else can it do?”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.