When we left Madison Grant, Teddy Roosevelt, and the Boone and Crockett Club, they were throwing their considerable heft behind unprecedented regulations on hunting in the United States. Their motive, however, was selfish: the rules would benefit them by keeping commercial hunters out of the mix, which meant more and bigger trophy bucks over the Roosevelt mantelpiece. But no charismatic megafauna is an island, and it soon became apparent to Madison Grant that people, animals, and the land were yoked together on the brink of an ecological precipice.Find Part One here.

The United States population in 1900 was less than a third of today’s, and not many people were worried about human development eating up the wilderness. The Sierra Club had less than 400 members. That’s not to say nobody recognized the value and finitude of natural spaces – amidst the first stirrings of industrialization in the early 1800s, heavyweights like Emerson and Thoreau bemoaned the loss of woodlands, and the idea of nature as a force for spiritual uplift was current in both high art and popular print throughout the century (the Library of Congress has the full text of such nature-themed hits as The Home Book of the Picturesque and _Wild Northern Scenes. This perspective was an aesthetic one, however. Ennobling nature was not yet embattled nature, especially with the popular gaze turned westward towards what seemed like a bottomless frontier. Thoreau definitely saw nature as embattled, but the popularized, sentimental stream of nature appreciation tended to filter out that element of his thinking and focus on the pretty scenery. Sleeping in a tent in the woods, which pre-1860 Americans tried to avoid whenever possible, became something you would do for fun.Thoreau’s argument for nature appreciation wasn’t aimed at Rocky Mountain vistas and the Grand Canyon, though. The East Coast was taking a beating in the form of relentless timber harvesting, and the environmental consequences were apparent to naturalists and to ordinary people whose towns were constantly flooded with eroding soil and debris. George Perkins Marsh, an extreme specimen of the 19-century-bearded-man-of-prodigious-learning, published Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action in 1864. This book synthesized European ideas about scientific forest management into a clarion call for Americans: "We must have a diligent eye to the requirements of nature, and must remember that a wood is not an arbitrary assemblage of trees to be … disposed according to the caprice of its owner."All of this is to say that a person like Madison Grant didn’t rise from the mists of his ancestral Long Island estate with his own notion of conservation already in place. The culture of nature appreciation and his close social ties to naturalists, conservationists, policymakers, and men of industry gave him a multifaceted view into what was going wrong in the heart of America’s forests. Grant had the luxury of not caring about the things that bound the other major stakeholders: industrial profits, consumer demand, popular opinion, scientific debate. He just liked to hunt. In the 1890s, Grant took a hiatus from backroom policy-making to establish the Bronx Zoo and study natural history. He wrote a series of scholarly articles about his old friends, the big game of North America. This period of study, in which he brushed up on the literature of George Marsh and many others, led him to a fairly radical conclusion about the future of wildlife conservation: in addition to protecting animals, it was necessary to protect their habitats. These animal habitats were also known as the public domain — immense tracts of western land open to exploitation by whoever got there first.The first National Park, Yellowstone, was created in 1872, but Congress was not eager to replicate this effort anytime soon. There had been a strong backlash from the logging and mining industries as well as from local settlers who feared the loss of their livelihoods. To get things rolling, Boon and Crockett Club member William H. Phillips slipped a line into the Civil Service Bill of 1891 that allowed the president to create "forest reserves" by executive order – these would become the national forests. The act passed without any debate, and without most Congressman realizing what they had done. The Secretary of the Interior, another Boon and Crockett Club member, convinced the President to sign the bill and quickly created 17 million acres of national forests – to the great chagrin of Western settlers who had made a very long trip in order to cut down trees that they could no longer legally cut down, and hunt game that they could no longer legally hunt.The reasoning behind the national forests, however, was not to put settlers and hunters and industrialists out of business. President Roosevelt explained to angry citizens that natural lands couldn’t be exploited all at once, but had to be rationally managed in order to yield their bounty for future generations. This is the reasoning of conservation – protecting resources so that they can renew themselves for ongoing human use. Gifford Pinchot, Roosevelt’s Chief of the Forest Service, considered anything less than the efficient maximization of timber production to be "sentimental nonsense."But Madison Grant had no love for modern efficiency. A gentleman doesn’t worry about money; the cult of efficiency struck him as uncouth, another signal of America’s precipitous decline. After 1905, he began a strange metamorphosis: he started to envision the national forests as game refuges, places where hunting – by anyone, even Madison Grant – was prohibited. He wanted Americans, including his Boon and Crockett Club buddies, to stop hunting simply because it was the right thing to do. This was preservation rather than conservation – Grant had become convinced that wildlife, from the passenger pigeon to his beloved Rangifer granti, simply had the right to exist.These two camps within the environmental movement are still with us today: "conservation for" versus "preservation from" human use. The preservationists (most famously John Muir, who fought for the National Parks not with backroom dealings but through public advocacy and tremendous eloquence) wanted natural land set aside for spiritual contemplation and edification, as retreats from the ills of the degenerating cities. With his mighty powers of persuasion, Grant convinced the Boon and Crockett Club, an exclusive organization devoted to big game hunting, to support a ban on hunting in the nation’s wildernesses.

In the 1890s, Grant took a hiatus from backroom policy-making to establish the Bronx Zoo and study natural history. He wrote a series of scholarly articles about his old friends, the big game of North America. This period of study, in which he brushed up on the literature of George Marsh and many others, led him to a fairly radical conclusion about the future of wildlife conservation: in addition to protecting animals, it was necessary to protect their habitats. These animal habitats were also known as the public domain — immense tracts of western land open to exploitation by whoever got there first.The first National Park, Yellowstone, was created in 1872, but Congress was not eager to replicate this effort anytime soon. There had been a strong backlash from the logging and mining industries as well as from local settlers who feared the loss of their livelihoods. To get things rolling, Boon and Crockett Club member William H. Phillips slipped a line into the Civil Service Bill of 1891 that allowed the president to create "forest reserves" by executive order – these would become the national forests. The act passed without any debate, and without most Congressman realizing what they had done. The Secretary of the Interior, another Boon and Crockett Club member, convinced the President to sign the bill and quickly created 17 million acres of national forests – to the great chagrin of Western settlers who had made a very long trip in order to cut down trees that they could no longer legally cut down, and hunt game that they could no longer legally hunt.The reasoning behind the national forests, however, was not to put settlers and hunters and industrialists out of business. President Roosevelt explained to angry citizens that natural lands couldn’t be exploited all at once, but had to be rationally managed in order to yield their bounty for future generations. This is the reasoning of conservation – protecting resources so that they can renew themselves for ongoing human use. Gifford Pinchot, Roosevelt’s Chief of the Forest Service, considered anything less than the efficient maximization of timber production to be "sentimental nonsense."But Madison Grant had no love for modern efficiency. A gentleman doesn’t worry about money; the cult of efficiency struck him as uncouth, another signal of America’s precipitous decline. After 1905, he began a strange metamorphosis: he started to envision the national forests as game refuges, places where hunting – by anyone, even Madison Grant – was prohibited. He wanted Americans, including his Boon and Crockett Club buddies, to stop hunting simply because it was the right thing to do. This was preservation rather than conservation – Grant had become convinced that wildlife, from the passenger pigeon to his beloved Rangifer granti, simply had the right to exist.These two camps within the environmental movement are still with us today: "conservation for" versus "preservation from" human use. The preservationists (most famously John Muir, who fought for the National Parks not with backroom dealings but through public advocacy and tremendous eloquence) wanted natural land set aside for spiritual contemplation and edification, as retreats from the ills of the degenerating cities. With his mighty powers of persuasion, Grant convinced the Boon and Crockett Club, an exclusive organization devoted to big game hunting, to support a ban on hunting in the nation’s wildernesses.After squaring away natural lands preservation, he turned his hand to preserving the human "master race."

This all sounds well and good to us: preservation as an end in itself, an appreciation that some of nature must be cordoned off from capitalism’s voracity. But certain more sinister logics underpinned early environmentalist thinking. There is a very good reason why no one talks about Madison Grant anymore in relation to virtuous causes like saving the redwoods or restoring bison herds. After squaring away natural lands preservation, he turned his hand to preserving the human "master race." His 1916 eugenic manifesto, The Passing of the Great Race, was translated into German in 1925 and adopted as the scientific foundation of the Nazi genocide. In perhaps the most damning fan letter ever, a young Adolf Hitler supposedly wrote to Grant that "the book is my Bible."Grant died in 1937. He never had to face the consequences of his eugenic doctrines in action, but he corresponded with enough Nazis that he may have had some inkling of what was to come. Even putting aside the fact that his book served as evidence for the defense at Nuremberg, Grant represented a pernicious apex of American xenophobia and racism: he successfully lobbied for immigration restrictions and bans on interracial marriage, he went state-by-state convincing legislatures to implement coercive sterilization of the "unfit," and he preached eugenic science to the American public. Eugenics was considered a mainstream science in the early-20th century. Eugenic enthusiasts – Grant’s well-placed friends in politics, science, and industry – looked at America’s changing population and saw their grasp on power endangered. Grant was a mere popularizer, spreading scientific racism out of what looks a lot like a deep-seated fear of his own mortality. Bigoted and profoundly anti-populist, he was only unusual for his time in that he got so many of these ideas enshrined in law.So we’re left with dodges. His ideas were insidious, but some of his outcomes were good. It’s likely that without him and his hunting buddies, the protected natural spaces that we cherish would be nonexistent or vastly diminished. However, what Grant meant by "nature" and "the natural" was not what we mean by it today. Nature was a hierarchy with Madison Grant at the top. It is part of the strangeness of American democracy that one powerful man, or corporation, or lobby, can outweigh the people’s voice; sometimes the people want to hunt endangered magpies, sometimes the people want to not die of cancer.All of us who care about the environment are perversely linked to Grant and his sense of preservation as a variety of melancholy. Grant felt melancholy because, as he relentlessly repeated in his writing, "the old order of things has largely passed away." This might resonate for us as we think about lost species and habitats, a global ecological balance thrown into freefall; but for Grant it meant his order of things, a nation where a few rich and powerful men called the shots.This article draws heavily upon Jonathan Spiro’s biography of Madison Grant: Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant (University Press of New England, 2009), as well as Garland E. Allen’s “Culling the Herd’: Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940” (Journal of the History of Biology, March 2012), and Madison Grant’s tracts, The Passing of the Great Race (Scribner, 1918) and “The Racial Transformation of America” (The North American Review, Vol. 219, March 1924) and “Vanishing Moose” (Century Magazine, January 1894). The Library of Congress digital collection, “The Evolution of the Conservation Movement”, contains a detailed timeline and a number of primary sources on American conservation throughout the nineteenth century; more on the history of the U.S. Forest Service can be found at the “Forest History Society”.

Eugenics was considered a mainstream science in the early-20th century. Eugenic enthusiasts – Grant’s well-placed friends in politics, science, and industry – looked at America’s changing population and saw their grasp on power endangered. Grant was a mere popularizer, spreading scientific racism out of what looks a lot like a deep-seated fear of his own mortality. Bigoted and profoundly anti-populist, he was only unusual for his time in that he got so many of these ideas enshrined in law.So we’re left with dodges. His ideas were insidious, but some of his outcomes were good. It’s likely that without him and his hunting buddies, the protected natural spaces that we cherish would be nonexistent or vastly diminished. However, what Grant meant by "nature" and "the natural" was not what we mean by it today. Nature was a hierarchy with Madison Grant at the top. It is part of the strangeness of American democracy that one powerful man, or corporation, or lobby, can outweigh the people’s voice; sometimes the people want to hunt endangered magpies, sometimes the people want to not die of cancer.All of us who care about the environment are perversely linked to Grant and his sense of preservation as a variety of melancholy. Grant felt melancholy because, as he relentlessly repeated in his writing, "the old order of things has largely passed away." This might resonate for us as we think about lost species and habitats, a global ecological balance thrown into freefall; but for Grant it meant his order of things, a nation where a few rich and powerful men called the shots.This article draws heavily upon Jonathan Spiro’s biography of Madison Grant: Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant (University Press of New England, 2009), as well as Garland E. Allen’s “Culling the Herd’: Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940” (Journal of the History of Biology, March 2012), and Madison Grant’s tracts, The Passing of the Great Race (Scribner, 1918) and “The Racial Transformation of America” (The North American Review, Vol. 219, March 1924) and “Vanishing Moose” (Century Magazine, January 1894). The Library of Congress digital collection, “The Evolution of the Conservation Movement”, contains a detailed timeline and a number of primary sources on American conservation throughout the nineteenth century; more on the history of the U.S. Forest Service can be found at the “Forest History Society”.

Advertisement

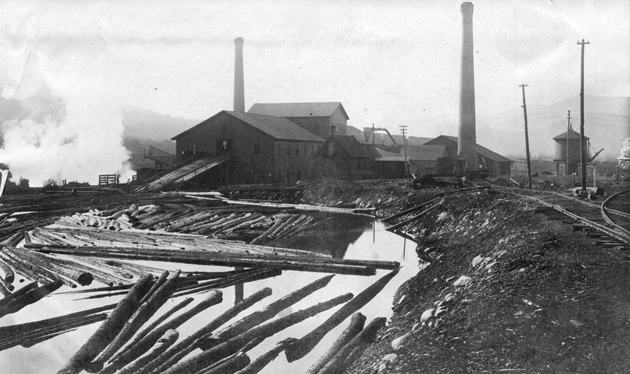

The North Woodstock, NH, sawmill, 1903

Advertisement

Passenger pigeon slaughter, 1884

Advertisement

Advertisement

After squaring away natural lands preservation, he turned his hand to preserving the human "master race."

_

Advertisement