Fermilab scientists watched Europe’s CERN announce its Higgs boson results starting at 2 AM on July 4th..

Advertisement

It was an overflow crowd to watch the presentations at 2am on the morning of July 4th, I would say close to 400 in total, which is remarkable. The group certainly consisted of many scientists that work on either the Tevatron or LHC experiments. But there were many other people, many young ones that recognized that this could be and was a seminal moment and wanted to be part of it.

Combined results from ATLAS and CMS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider.

Our job will be to characterize this new particle and to continue to look at the data for other surprises. This may not be the only big announcement from the LHC in 2012. We will see. The implications of this are broad and will be felt in other fields. If this is a super-symmetric Higgs, then we really are in an entirely new world.Are we getting any closer to understanding other giant questions, like where the Higgs and the universe came from?

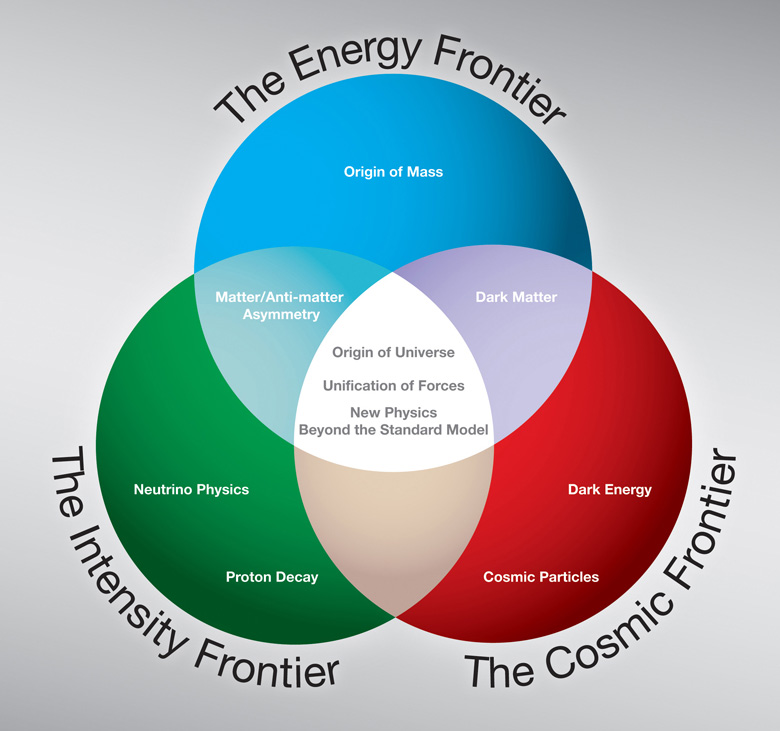

Physicists can answer the question of the Big Bang at that instant and how it manifests itself into the world we live in. We can't look at what came before the Big Bang; that's for philosophers to address. Basically, physics starts with the Big Bang so we have no tool to look prior to it. But higher powered accelerators get you closer and closer. After the LHC turns off for a year and a half next year, and turns on with a higher energy, that will teach us that much more. So we're not at a limit at all. How we go forward depends upon what we find this year, and in the next couple of years, if there are things between 4 and 8 TeV these experiments will start to uncover them. For now, we continue to characterize the Higgs boson and see how it acts. These LHC guys have a tremendously amazing data set and they will search for new physics in that data set, and they will continue to search for new physics this year to see if they can find evidence for new symmetry or something else in their data. Fermilab is barking down this intensity frontier to look at rare processes that are difficult to do on the energy frontier.

Advertisement

Neutrinos [- the rarely-interacting particles that might help explain why the universe bloomed and didn't annihilate itself] are behaving differently than what we expected. They didn't fit the mold of what was the Standard Model of 10 years ago. It's a place where the Standard Model is broken, and we need to understand what it's telling us. [The Earth is bombarded by neutrinos from the sun all the time; by using more intense beams of neutrinos, scientists can more easily detect and study them.] So Fermilab is already engaged in the intensity frontier in running its current experiments. It's about to send a new neutrino experiment online called NoVA, which will start taking data at the end of this year. And it wants to build another facility out in South Datkota called LBNE, the Large Baseline Neutrino Experiment, which would shoot a larger, higher-flux set of neutrinos.And the holometer, meant to test the idea the universe is just a hologram? How's that doing?

They got funding to do at least the first round of it, so they're busy putting it together, making it work.

The schedule for Fermilab’s next “intensity frontier” accelerator, Project X, is being amended to reflect belt-tightening at the Dept. of Energy.

Fermilab is still running accelerators. Not the Tevatron, but it's running the rest of its program. Most of the accelerators it's running right now are forty years old. Project X replaces a current infrastructure and updates and modernizes it to give it much more capability than what we currently have. We're in the process of putting together a design package and a cost package to try to get approval from the Dept. of Energy so we can build it. Until it gets approved it's hard to know when it could be built. The DOE is very much on board with wanting to do this project. But this federal budget issue – whether we're all going to take a ten percent cut across the board in January 2013, how this plays out – has a huge impact on when large projects start, and how other projects continue.Is this an an exceptionally unusual time when it comes to resources for big science?

These are difficult times for everybody. Basic science may not be increasing in scope the way most of us want to see it. But it also hasn't taken a huge hit either. There's a certain recognition among both the voters and the lawmakers that fundamental scientific research is important for the long term prosperity of the country. It's just a matter of how you balance that long term stuff against the immediate needs of the other problems that you're facing. I think we are closer than ever to answering the most important questions facing us right now because we now have the technologies that are available to us. But how well we do that will be determined by the level of dollars, not just in the U.S. but worldwide that go toward answering these questions. So it's a great time and a frustrating time to be a physicist.

Advertisement

Hitler reacts to the closing of the Tevatron.

These big facilities are all built with an end date in mind, because they should be replaced with something else. Turning the Tevatron off is not a political statement at all; it's just the reality that this machine had served its useful life, and now that we have one that's better, that's working well… We can quibble about whether we should turn it off now or a year later, but we live in a world with finite resources and we should optimize those resources as best as we can. I'm impressed that people outside the Batavia area even knew about it, which is always good. I think scientists are doing better at outreach, exciting people about the work we do, but I think we could be doing more than what we have.Is it tempting to see the shutdown of the Tevatron as a sign of America’s decline?

I'm not sure that's fair, but it can be viewed that way. I tend not to think conspiracy but you can think stupidity. I think sometimes… The world we live in is tough, right? There's a finite amount of resources. People are having a tough time with ten percent unemployment. So I can't be too grievous that we didn't get the next hundred million dollars we needed to start the next project. We have to temper it with reality.

Watching the LHC results from Fermilab, 3 A.M., July 4. Bottom: Rob Roser.

Believe me, it did hurt. In the end there's a pride thing that wants to be first. But there's the scientist that just wants to know the answer. At least I'll get the second, even if I don't get to be part of the team that actually did it.When all is said and done, how will the researchers and the engineers involved – not just the theorists – be celebrated? For instance, by a certain prize committee?

I have no idea. It's very complicated because there's an awful lot of people that have enabled the field to get to this point. Whether it be the accelerator guys who have been able to produce fantastic machines, the tester guys who have built the level of precision required. There are so many collaborators. Maybe they will punt and not give one out, or maybe just give one to the people that came up with the theory. But I don't know.