Activists and tribal members Kandi Mossett, Dean Dedman, and Dallas Goldtooth are racing to release new footage of the protests against Energy Transfer Partners, which is building a controversial four-state oil pipeline from North Dakota to Indiana. They can’t get solid reception at Highway 1806 in North Dakota, where they’re calling me from, so they’re deciding how to upload the content quickly. Phone reception begins to break up.

Police have just arrested 144 protestors—they call themselves water protectors—and over the phone I can hear Dallas describing how a private security agent brandished an AR-15. Dean shouts that they’re heading to find a strong internet connection, then hangs up. Meanwhile, I chat with Kandi to find out what’s been going on.

Videos by VICE

“I’m out there with my three year-old daughter, looking in the face of police in full riot gear, with mace in cans the size of small fire extinguishers, with their huge guns like something out of Rambo,” said Mossett, who’s been demonstrating along Highway 1806, the site of the standoff between water protectors and law enforcement.

On the other side of the highway is the Missouri River, which developers want to place pipe under. “You could see they were ready for action,” Mossett said.

The ‘best signal in the area’ isn’t on Facebook Hill

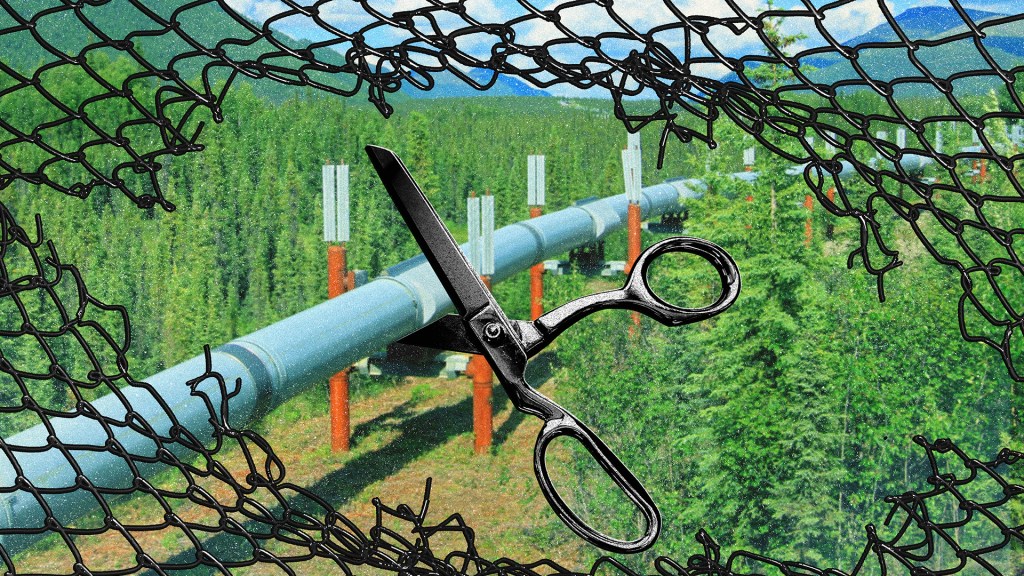

The encampment protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline are heating up. Starting in April, self-described “water protectors” from Standing Rock Sioux Tribe began occupying land near Bismarck, North Dakota, to halt construction of a four-state oil pipeline, saying it could poison their water supply. Then on September 9, shortly after footage emerged of dogs attacking water protectors, President Obama called on the US Army Corp of Engineers to review the risks of submerging an oil pipeline under the Missouri River, which supplies drinking water for 18 million people.

On October 10, celebrity actress Shailene Woodley streamed coverage from her phone, raising awareness that construction was also happening on Indian burial sites. She was arrested, as were an additional 126 people on October 22. Thousands of tribal members have visited from across the country and Canada. The National Guard has been called in and a state of emergency declared. On Thursday, law enforcement began a coordinated operation to remove protestors.

“We bring our drums and our medicine,” Mosset said. “But we’re working with other tools, too. Mark Ruffalo is here to help us build a mobile media van. Right now all we’ve got is the reservation and our headquarters, Facebook Hill.”

“I’m out there with my three year-old daughter, looking in the face of police in full riot gear, with mace in cans the size of small fire extinguishers, with their huge guns like something out of Rambo.”

Facebook Hill is part of a ridge where water protectors have attempted to get cellular service in an area notorious for its spotty coverage. Below the ridge sits a more permanent encampment which has been occupied by water protectors since April. The land is considered property of the US Army Corps of Engineers. It’s likely where many will retreat to, now that the standoff at Highway 1806 is dispersing.

“Most of the land out here is for cattle grazing, so the connectability challenge is great,” said Eileen Williamson, spokeswoman for the US Army Corps of Engineers. Water protectors claim that coverage has been complicated by the presence of police IMSI catchers, commonly known as StingRays or TriggerFish, which mimic cell towers in order to obtain personal data from phones. “We’d be using our phones, and all the sudden the batteries would get sucked down really fast,” says Mossett, describing a telltale sign that a StingRay is being employed.

Just a few miles to the south, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is inviting people to their reservation, to stage a camp equipped to withstand the coming winter and North Dakota’s subzero temperatures, away from construction sites.

This isn’t necessarily to suggest defeat—it’s just that the tribe owns and operates its own telecoms company, and the reservation gets one of the best signals in the area. Dallas Goldtooth, a YouTube personality, described the frustrations of recording demonstrations in the field, then rushing back to the reservation to upload footage. Meanwhile, law enforcement had already put out its own contradictory message. Standing Rock Telecoms head manager Fred McLaughlin told me this process has been painful to watch.

“It’s like this ever-revolving door,” McLaughlin said. “I’ve got the equipment and know-how to get a small tower out there, but encampments are shifting so quickly, they tell me to hold off, and then before you know it we’re going weeks without a decent internet connection out there.”

“Right now all we’ve got is the reservation and our headquarters, Facebook Hill.”

“I do take personal responsibility for that,” he said with a sigh. “[The water protectors] want the capability to upload high-quality video, even do radio, to show directly what’s going on. But this area isn’t made for high-traffic internet. It’s not just a matter of setting up a little tower and shooting point-to-point internet at them, from our main tower here. It’s a line of sight issue. The camp is sitting below a ridge.”

“Here’s my email address,” he said abruptly. “I can tell I’m about to lose you soon.” A few minutes later, the call died and McLaughlin’s phone went straight to voicemail.

Native American culture is cyberculture

Many have lamented that climate change and renewable energy received little attention during the recent presidential debates. Donald Trump owns stock in Energy Transfer Partners, the company building the pipeline, and Hillary Clinton has received twice as many campaign contributions from fossil fuel executives ($525,000 in total).

So it’s interesting to read theories that Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other Native Americans are being used as pawns by environmental activists. It’s an easy conspiracy narrative to grasp: by pitting the earthy, anti-tech indigenous peoples against techno-bureaucrats, these covert eco-activists will get everyone to support their cause for renewable energy. Even if true, this doesn’t sound terribly bad?

But the story just doesn’t hold up any ways. Turns out, members of Standing Rock Sioux Tribe are seasoned tech entrepreneurs who could go head-to-head with any hoody-wearing, Soylent-slurping Silicon Valley whizkid. They’re also deeply concerned about finding ways to cover this issue themselves, through a variety of media.

What’s more, if you dig deeper, you can find that American cyberculture is strongly tied to tribal values. The only thing propping up this conspiracy is the long historical backlog of American entertainment that has painted Native Americans as technologically backward It risks turning the pipeline protests into a modern version of “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show,” an 1880’s carnival production in which Native Americans from the Dakotas were recruited to “play Indian,” as author Vine Deloria puts it.

“Just because someone is protesting one type of technological intrusion doesn’t mean that their embrace of other technologies is somehow ironic. It’s a sign of technological sophistication, not a fruitless protest against modernity, as I think is sometimes shown in the media,” said Andrew Kirk, a history professor at the University of Nevada.

“The idea of small-is-beautiful is important here I think,” Kirk continues. “This was an ethic popularized by the American counterculture but quickly adopted by indigenous peoples globally as a means of reconciling nature, culture and technology.”

Kirk’s friend at Stanford, Fred Turner, has written about the connection between tribal values and American online culture in a recent book, From Counterculture to Cyberculture.

In particular, Turner focuses on Stewart Brand, one of the original Merry Pranksters who rode an LSD-stocked school bus across America in the 1960s. Brand also spent time on reservations, took peyote and married a Native American. Turner goes on to write how Brand channeled his tribal experiences into WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link), one of the first online communities to emerge in 1985—with servers located on a hippie commune in Tennessee of all places. WELL had an analog compliment, called Whole Earth Catalog, which was described as “Google in paperback form” by Steve Jobs.

Brand declined to comment on the pipeline protests, other than to humbly note, “I’m too ignorant of this one to be helpful.” (For what it’s worth, Brand is actually a polymath who’s currently building a clock with a 10,000-year lifespan.)

“[The counterculture] could be united as a tribe within an information medium and they could use that medium as a tool, like LSD, to achieve a recognition of the information patterns and energy that linked them to their fellows and to the natural world,” Turner writes.

All of this cultural history is coming to bear on the pipeline protests, as water protectors bring together a mix of ancestral practices and tech know-how, in order to develop their identity, stay in touch with each other and communicate a message to the wider world.

The sight of a heavily militarized police force on the Great Plains—while water protectors aim for “small-is-beautiful” with mobile media vans and drones and smartphones—well, it’s a sight not lost on anyone. Six state police departments have been called to Bismarck, and as The Economist reported last year, between 2002 and 2011, the Department of Homeland Security disbursed $35 million to state and local police for high tech gear. Here’s the whopper from that report: 90 percent of towns with 25,000 people have a SWAT team in place. This says not only a lot about America’s police force, but about how it’s actually the wider American public, not Native Americans, who dance between love and fear of technology.

“It’s a sign of technological sophistication, not a fruitless protest against modernity, as I think is sometimes shown in the media.”

So it looks like Kirk is on to something: just because Native Americans reject the outsize oil pipeline, doesn’t mean they’re de facto bow-and-arrow wielding “rioters,” as militarized law enforcement has called them. They just prefer “small-is-beautiful,” an intuitive approach to tech that doesn’t require commercial or state experts. For example, don’t build oil pipelines near major drinking water sources. Or don’t use StingRays that prevents using smartphones to document police presence. These are, again as Kirk remarks, sophisticated approaches to technology that show an understanding of scale and risk. The water protectors have more in common with Stewart Brand’s WELL and the early iPhone culture which he inspired Steve Jobs to create, than the public may realize. In fact, Obama announced his rural connectivity program last year to an excited indigenous tribe in Oklahoma.

More likely what’s happening is that the protests are exposing the wider public debate over shared resources, with some preferring to say that issues are too technical to be handled by anyone other than large state actors (like militarized police) or developers (like fossil fuel companies).

Whoever controls the media, controls the narrative

That’s still not stopping conspiracy theorists who wish the controversy would end, so that things might get “back to normal.” North Dakota media, largely pro-pipeline, have been giving fodder to angry locals. Rob Port, who blogs at a number of publications like Say Anything, seems to draw this crowd out, with articles titled, “Standing Rock has set themselves up to lose big.” In that latter article, Port writes how protests are a front for eco-agitators: “We cannot let the politics of extreme activists, or the narcissistic antics of celebrities, harm what should be our most important goal, which is comity between tribal and non-tribal communities and a unified, neighborly spirit as North Dakotans.”

In his latest post for Say Anything, Port rips into the water protectors, again based on a Morton County Sheriff’s Department report that bows and arrows were present when a police helicopter flew overhead. Port’s commenters litter message boards below his articles with claims like “They want violence” or “Has occupy Wall Street come to the prairies?” These commenters seem to have forgotten that, earlier this year, white farmers sued against the eminent domain practices of the Dakota Access Pipeline. They also seem to have forgotten how the Bundy occupations, centered on letting private cattle graze on public lands, took a heavily Luddite stance that lingered long before the arrival of militarized police.

This story does have a clock on it. If oil is not flowing through the pipeline by January 1, then the suppliers can cut their contract with the developers. Originally, the pipeline was planned to go north of Bismarck, but municipalities rejected that on grounds of risk. For now, the standoff remains at Highway 1806, where the pipe waits to be dug under the Missouri River. Water protectors are claiming that adjoining land was ceded to the Sioux in a treaty.

It’s important to note how conspiracy theories are supported, or even engendered, by the militarized police presence ramping up at this site. As Standing Rock chairman Dave Archambault has noted, this presence creates the appearance of dramatic pushback, as the public has seen in other places of social unrest and heavily outfitted police departments, like Ferguson, Missouri. Archambault is calling on the Department of Justice to intervene, out of fear of escalating police tactics.

The battle for the air and the airwaves

Back at Facebook Hill, Dean Dedman, Dallas Goldtooth and Kandi Mossett, the water protectors, are shaking their heads over allegations. “The local police have claimed we used bows to shoot arrows at helicopters,” laughed Goldtooth, a Dakota tribal member who produces skits about Native American stereotypes. “There have been over 200 arrests thus far, and not one weapon produced.”

Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier and his spokeswoman Donnell Preskey did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this matter.

“There’s been a media blackout for so long on this issue, we’re dependent on social media.”

If any aerial attacks have been recorded, it’s been by police against Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Dedman knows, as his drone was shot down on October 23. He was using it for his media company, Drone 2 be Wild. Shortly thereafter, the FAA instituted a no fly zone for drones in the area.

“For the past three months, activity has been spread out over 30 miles west of the Missouri River, now it’s concentrated into an eight-mile swatch,” Goldtooth said. “We’ll see and hear drones overhead at night, it’s really eerie.”

“Yep, we’ve started to see drones we can’t identify,” Mossett asserted. “The police even charged one of our licensed drone operators, Myron Dewey, we partnered with him to produce media from our camp. They confiscated his drone, it’s still in their possession. That’s thousands of dollars. There’s been a media blackout for so long on this issue, we’re dependent on social media.”

“So we’ve got to work with Freddy [McLaughlin], to boost our signal, he’s got that tower on the other side of these hills,” Goldtooth replied. “Our only other hope is death by delay. Stop this pipe by waiting it out.”

“It’s more intense than it ever has been,” Mossett said to me, before everyone left to meet with Mark Ruffalo about building that mobile media van.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.