On Edge is a series about stress in 2017.

It was easy to blame it on New York.I had been waking up for five months with an angry, sour anxiety in my stomach—transitioning from a restless sleep to the cold reality of a bleak winter day. It started sometime in October 2016 after a rough break-up, accelerated with the election news cycle in November, peaked when I had a falling-out with a close friend in December, and persisted through the winter, with the relentless grey sky like a weight on my shoulders.

It was easy to blame it on New York.I had been waking up for five months with an angry, sour anxiety in my stomach—transitioning from a restless sleep to the cold reality of a bleak winter day. It started sometime in October 2016 after a rough break-up, accelerated with the election news cycle in November, peaked when I had a falling-out with a close friend in December, and persisted through the winter, with the relentless grey sky like a weight on my shoulders.

Advertisement

Everyone around me seemed to be battling similar demons. The day after the election I saw two people veer off the bike path and into the sidewalk for no apparent reason. In the newsroom, monitoring social media and breaking news nine hours a day, we found ourselves covering the most peculiar and jarring political environment we had lived through. I love this city, but suddenly its crowded streets and disquiet felt suffocating.

I’m not good at wallowing in despair. If I’m feeling shitty I leave countries and find psychologists and read books and show up at meditations until I find my way back to a good place. So on March 16 I started to look up therapists and made an appointment the next day. In April I enlisted the help of an integrative medical doctor to actually hack my stress levels through a series of diagnostic tests and interventions. By May I had cobbled together a plan to make peace with the city, and understand how people can thrive in it.But I didn’t know what the rest of the year held.*Dr. Chiti Parikh told me the most stressed-out people in New York are the ones who don’t know they’re stressed. I knew I was stressed, though, when I showed up in her office at the end of winter—pale, sick, and on edge.Parikh, one of the physicians running NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center's new Integrative Health and Wellbeing Center, is used to people coming in at their low points. Her team is not what you would expect at a hospital: It’s comprised of physicians, but also nutritionists and mind-body nurses, who have studied alternative therapies like reiki and acupuncture.Everyone around me seemed to be battling similar demons

Advertisement

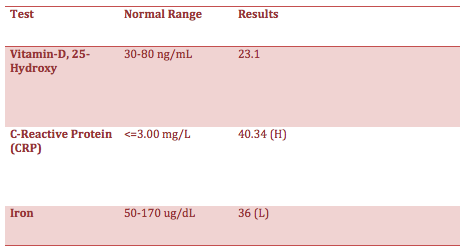

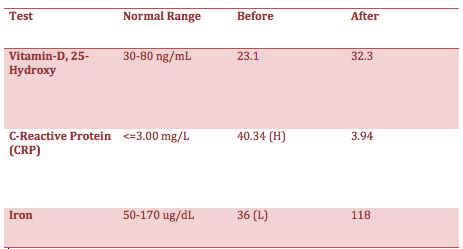

On April 18 I had my first consultation. We talked at length about my medical history, stressors in my daily life, and how they were manifesting through physical symptoms. Parikh asked questions like, “What gives you sense of purpose?” and “What brings you joy?” Then we did what can only be called a shitload of blood tests and a physical exam to find out my baseline. I also tested my cortisol, aka the “stress hormone,” by spitting into a series of tubes throughout one day.If I needed a clinical set of data to prove my stress was real, this was it. I consider myself generally healthy, but within a week, I found out I was anemic and Vitamin D deficient, with fluctuating cortisol levels and high inflammation markers, which can mean vital organs like the liver are not functioning at their best. Here was my stress living in my body and blood with me.

Cortisol, the stress hormone, levels in April.

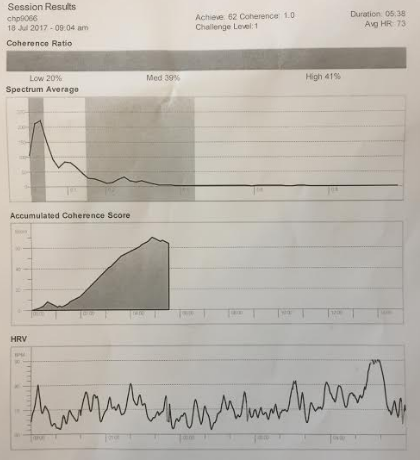

I had already started therapy to address some of the root causes of my anxiety. But making your body more equipped to handle stress is important. Based on my results, Parikh helped me devise a strategy: iron and Vitamin D supplements, a monthly reiki and acupuncture regimen, and sessions with the in-house nutritionist.The final prescription was to meditate for 10 minutes twice a day using a system called Inner Balance. This is essentially a device that you clip onto your earlobe that measures your heart rate variability—the space between beats—and an app that helps you calibrate your breathing. Parikh said if you do it right, you can sort of trick your body into thinking you are relaxed, even if the mental anguish is alive and well. The first time I did it at her office computer in July, my coherence level—essentially the measure of emotional states impact your nervous system—was 62.

Advertisement

Outside, there was suddenly an extra hour of sun.*I am not the most stressed-out person in New York City, not by a long shot. Brunilda Rivera is. That is to say, she falls in a certain cross-section of society that is most vulnerable to the stress of modern life: she is a woman of color, a single mother, and low-wage worker.As a single mother, Rivera, 52, is a part of a subgroup that is more likely to fall sick than their counterparts. As a Latina, she is also more likely to fall through gaps in our health system—going to the doctor less regularly, and receiving fewer preventive screenings like mammograms.And at a time when social supports like food stamps are being threatened, every day is difficult. This year her son, a 21-year-old college student with learning issues who is dependent on her, became ineligible for food subsidies, leaving Rivera with steeper bills that her part-time job at the crafts store Michaels doesn’t always cover.

Rivera. Image: Women's Prison Association

“This whole year has been crazy for me,” she said. “I’m struggling to just live. I bust my ass every day, and I’m just making ends meet.”Rivera has experienced the full spectrum of our country’s broken systems. She grew up poor on the Lower East Side, left home when she was a teen, was incarcerated while trying to hustle her way through her 20s and 30s, had five children, and found few job opportunities open to her when she tried to get her life together. She finds support through the Women’s Prison Association, a nonprofit that supports women who have been incarcerated, through which I met her.

Advertisement

As she struggles to put food on the table in Bed-Stuy, a quickly gentrifying neighborhood in Brooklyn, the daily grind leaves her depleted. Rivera said she has a headache every other day. She tries to take care of herself—she and her son have been trying to follow a healthier diet and she lost 40 pounds to bring down her blood pressure. But it’s hard to find time to even think of her own mental health.“I know one thing’s for sure, when I am stressed, all I can do is breathe and make phone calls to people that I can vent to,” she told me. “But life is hard.”*Rivera and I live vastly different lives in the same New York, a city built on its stress in many ways. As the sayings go, it’s the city that doesn’t sleep, the city where if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere, the place where time is compressed in a New York minute. And that’s where attempts to soften individual stress fall short.“I think there’s something about that attitude of ‘Nothing is going to stand in our way’ that is still in the general atmosphere of the city’s sort of aggressiveness,” said Melissa Checker, an urban studies professor and anthropologist at Queens College and City University of New York.

A few months into summer I was adhering to Parikh’s stress-less regimen as best as possible. I was meditating daily, trying to do things that brought me joy like yoga and cooking, going to therapy, and taking my supplements. I had visited Cornell’s mind-body nurse, Manna Lu-Wong, who had led me through a blissful 45-minute reiki session, in which I honestly don’t remember what happened.

Advertisement

Middle of the summer, feeling pretty good. Image: Gaurav Madan

Then I got hit by a car when riding to work on a bicycle, suffered a concussion, and have since spent three months with almost daily headaches.If you ever want to put a magnifying lens on New York’s triggers, a brain injury will do the trick. Every noise, every inhale of smoggy air, every medical bill—everything that would normally be another drop in the bucket now meant hours of pain and frustration. I would lay in bed, picturing myself alone in a forest, protected by the quiet of trees. Then I would open my eyes, and the city was back.And what a city it is. Unlike Paris or Washington, DC, New York wasn’t carefully planned by architects. “New York grew up more haphazardly,” Checker told me. Before 1916, builders could start projects wherever they wanted in the Big Apple, and skyscrapers cropped up with abandon. Robert Moses, considered the main force of New York urbanization in the 20th century, designed the city with highways alongside the river, so unlike cities where you can stroll along the waterways, much of the water that makes New York an island is inaccessible to residents.

The chaos is a double-edged sword. In some ways, this relentless growth is what made New York an economic powerhouse, blasting through the distress of multiple wars, and reviving itself after every minor or major recession. But in other ways, this has created the city that makes a lot of us sick—it’s noisy, the parks are scattered, the roads are congested, and the buildings block out the sun.Every noise, every inhale of smoggy air, every medical bill now meant hours of frustration

Advertisement

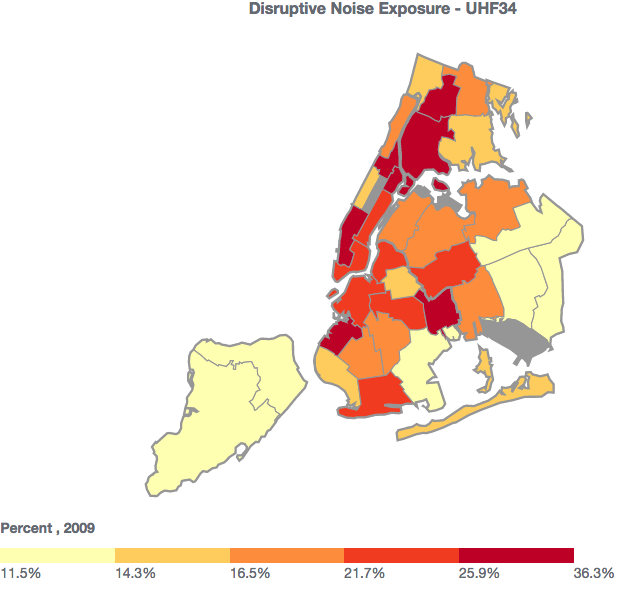

*Where you live in New York can often reveal something—not everything, of course—about your stress levels.Noise pollution often seems subtle, but disrupts sleep, and confuses your body so that it can’t differentiate as easily between times it should react to danger and times when it should be at rest. In noisy situations, our minds become more agitated, and our bodies remain on high alert. Noise pollution has been associated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease, psychological issues, and other stress responses. In 2009, the latest data available from the city, the neighborhood with the most complaints of noise issues is East New York, on the edge of Brooklyn.

Air pollution, meanwhile, is harder to track by neighborhood, but manifests in health issues like asthma and respiratory illness. New York has curbed its pollution rates since the 20th century, but polluted air still causes an estimated 2,700 premature deaths every year. According to the New York City Community Air Survey, congested Midtown Manhattan is the worst place for clean air, but Harlem has the highest rates of asthma, a consequence of poor air quality.

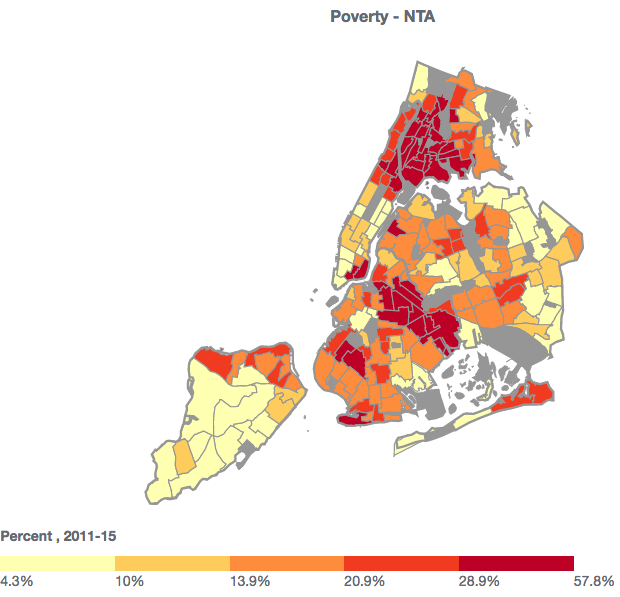

If you ask people in New York why they’re stressed out, though, they usually don’t say because of the air they breathe, or the noise. They say money. New York has some of the highest rents in the country, and everyday expenses can be double that of outside the city. An estimated 66 percent of New Yorkers in a 2011 survey said housing costs are a source of stress, compared to 49 percent across the country. This is especially difficult in neighborhoods like Tremont, in the Bronx, and Brownsville, in Brooklyn, the two areas with the highest rates of poverty in New York City.

Advertisement

“I have no idea where people are supposed to go,” said Shaddia Wilkins Torres, the program director at a Brooklyn Community Services mental health clinic. “Many people rely on vouchers like Section 8 [affordable housing] just to subsidize their living, but with gentrification, some landlords opt not to take them.”I met Torres on a busy day of organizing group therapy and clinical visits at the clinic in Canarsie, Brooklyn. The clinic serves a low-income population, mostly from economically strapped neighborhoods like Brownsville, East New York, and the Bronx, where access to healthcare and insurance is low. She said gentrification is pushing people out of their communities, and usually to more unstable places, away from jobs and their families.In some ways this disparity is baked into New York City’s design. Checker pointed out to me that when the city first started to create zones, the poorest people lived right next to manufacturing hubs to make it easier to work in the factories. Rich people, meanwhile, moved into more protected, residential areas. This meant the poor neighborhoods were subjected to the noise, pollution, and bustle of the working city, while others got parks and buffers from the same hustle.

Torres said the stress is inevitable for most of her clients—they are fighting mental and physical illness, housing issues, incarceration and violence. And it manifests in brutal ways. People are twice as likely to die from heart attacks in poverty-stricken neighborhoods in New York, and children in these areas of the city are more than twice as likely to end up in the hospital for psychiatric problems.Disparity is baked into New York City’s design

Advertisement

But Torres said there are ways to make people in these communities more resilient. A lot of it comes down to family, which so many transient people in New York can lose along the way. “I’ve found that people who cope with stress the best are those with a solid support network,” she said. “Those are people who are able to bounce back.”*Resilience sometimes sounds like too soft an antidote to what we’re facing today, but it’s what everyone—Torres, and Parikh, and my therapist—talks about.Part of it is because both stress and resilience are universal. Rivera has, in many ways, been let down by the promises of growth and opportunity in New York, but it’s her resilience that has given her energy to find a job, cook kale and garlic for dinner, and overcome losing four of her closest family members in the past two years.While it takes time to change and impact the structures we live within, the ones that are bearing down on us each day, it’s much harder to fight them when you are tired, depleted and anxious. Managing stress takes us from our perch on the edge, ready to be pushed over, to a little more stable ground.I walked into Parikh’s office at Cornell for my final appointment in mid October. The year had been rough, even after March. My apartment flooded, and I had to move out for a couple of weeks. The bike crash and concussion had changed almost every part of my lifestyle, and impacted my ability to work, drink, hangout with friends, exercise, and think. My personal life remained a roller coaster, between dating, family, and friends.

Advertisement

But it turns out the one thing I had figured out in the past six months was resilience. My blood tests came back improved. My cortisol levels revealed a much healthier, calmer day, albeit with a peak of stress in the morning caused by concussion headaches. I still had, and have moments of anxiety and tension, but they don't last for days, or even through the night very often.

Before and after cortisol levels.

And meditation—that thing that everyone tells you to do, but you can rarely tell is working, bore fruit, at least according to my Inner Balance app. I knew how to breathe in a way that, at the very least, convinced my body I was fine. My ability to react less to the disturbance of a wayward thought took me from a coherence score of 63 in July to 256 in November.

Before and after coherence levels from Inner Balance.

It goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: I could afford to focus on my stress. I have health insurance that covers a large part of my therapy and doctors appointments. I work for a company that didn’t fire me or cut my pay when I couldn’t work for a few weeks after my accident. I have access to food, and doctors, and a stable apartment. I have a supportive family and friends who show up for me.Now it’s starting to be winter again. The days are dark, and the news is maybe even worse than this time last year. Some problems in my life remain unresolved. Some of them still make me a little crazy. Yet I sleep well and wake up better. I meditate every morning as if it’s involuntary. And I’ve realized that the best thing I could ever do about stress is to, as Parikh says, acknowledge that it is real.These days I still blame New York, but I’m finally finding the energy to make it the city that I want it to be. Because I don’t plan on leaving any time soon.Listen to a Radio Motherboard interview with Dr. Chiti Parikh here.