I.

The Monitor, an unassuming vessel crewed by the Shellfish Department of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, was on a sample-gathering run through a tract of the Puget Sound off Tacoma, Washington, and faced little wind. But even on a serene Thursday morning in early March, partly sunny and otherwise clear, it may as well have been night 55 feet below, where Hozoji Matheson-Margullis sauntered through the disorienting thick of a silt cloud.

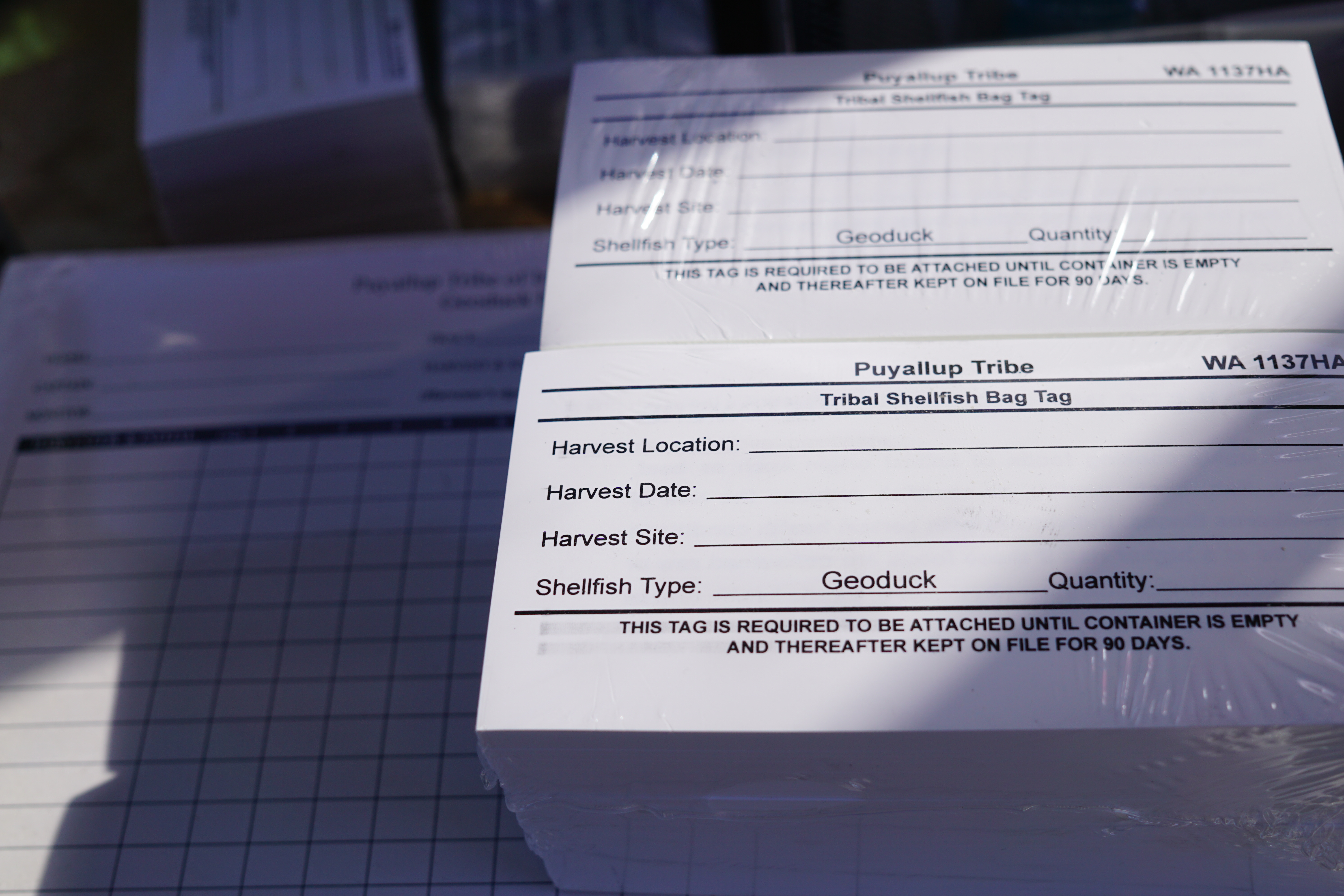

Geoduck in hand, Hozoji scoured the seafloor. The tract has been open for tribal harvest for three years, according to Monitor captain and Puyallup shellfish biologist Dave Winfrey. It was flagged recently when a 1,300-pound shipment of geoduck (“gooey duck”), a type of large, edible saltwater clam, sourced from a Puyallup fishery and headed to China, was recalled due to paralytic shellfish poison, a toxic algal bloom phenomenon commonly known as red tide. The Monitor’s assignment that day was to catch at least three geoducks for biotoxin analysis, to make sure that any animals harvested at the site were in fact safe for human consumption.

Videos by VICE

Native to the coastal waters of the northwestern United States, geoducks are bivalves with retractable, fleshy siphons for sucking in water and filtering nutrients before shooting the spent water back out. A mature geoduck is typically the length of the average adult forearm, weighing a pound or two, though the animals, fixing themselves to the same spot in the seabed, away from predators, for life, have been known to reach 6 feet and up to 14 pounds.

Geoducks look like disembodied infant elephant trunks, but one could be forgiven for thinking the animal resembles another sort of trunk entirely. The etymology of the common name traces to the Lushootseed word gʷídəq (“gweduc”), which translates to the phrase dig deep, although the suffix “-əq” may also mean “genitalia.” Any confusion on that point, I’m told, is due to mere dialectical differences.

Regardless, there is no known burrowing clam on Earth larger than Panopea generosa. And with lifespans that push a century-and-a-half, geoducks are one of the planet’s longest-lived critters.

The proper way to harvest a geoduck, Hozoji explained, is not by yanking the siphon, or “neck,” which risks tearing it from its base. Rather, one must bore under and around the clam’s shell. Dig deep.

Hozoji, now 37 and known internationally as a powerhouse drummer, remembers getting squirted by geoducks at low tide, while exploring the shores of her native Tacoma as a kid. Back then, she hung on a question that has shaped her existence ever since: What’s down there?

Today, the geoduck has become a harbinger of climate change. A growing body of research suggests that global warming and ocean acidification will exacerbate blooms of certain toxic algae like red tide, to the point shellfish like geoduck could become too poisonous for animals and humans to consume. That cuts especially close to home for Indigenous communities like the Puyallup, who despite being protectors of natural resources and stewards of sustainability, have historically been marginalized by non-native political and industrial forces.

The US government, all the while, has deferred to Western scientists, not deep-seated native knowledge and technologies, still a lingering, systemic bias in 2018. Data is hard to come by on the current number of Indigenous scientists in the US. As of 2011, the US Census estimated self-identified Native American and Alaskan Natives made up 0.6 percent of STEM jobs compared to 66.9 percent white (non Hispanic or Latino). Hozoji is uniquely poised to help close this gap: She came up through the tribal system and is now actively working to integrate herself into the scientific establishment. Last year, she landed a non-student position at a University of Washington-Tacoma (UWT) laboratory that is focused on tracking baby shellfish.

Hozoji is doing the work of an ambassador of Native American conservation to the traditional research-industrial complex, putting her in an insurgent, if precarious, position as a young woman on the frontlines of Indigenous science.

Which, when you’re 50-plus murky feet below the surface of the Puget Sound, means it can be hard to see what’s coming at you.

THE WAY DOWN

Wearing two-thirds of her body weight in scuba gear that calm March morning, Hozoji groped the underwater haze. The sediment had been stirred by a high-pressure water hose that Hozoji used to dislodge the geoduck. That’s when Hozoji noticed the silhouette, a looming presence, as it materialized no more than an arm’s length in front of her.

It was George Stearns, Hozoji’s dive partner.

“I couldn’t see him at all! And I’m waving this geoduck around,” Hozoji laughed, assuming she’d given Stearns, there to gather the specimen in a mesh bag, an accidental mollusk facial.

It was the kind of jumpy close call that comes with a gig in the gloom and, besides, Hozoji had experienced more serious brushes with danger earlier in her diving career. It’s something Hozoji and Stearns would joke about as they clambered back onto the boat’s cramped deck, replaying the near-miss. It was just one of a dozen geoduck Hozoji collected in a little under a half-hour during a sweep of this pocket of a larger shellfish grounds, which, like other tribal tracts, encompassed roughly 100 acres.

Puyallup strategy is to harvest 65 percent of the biomass in a given hundred-acre tribal tract, such as this one, and then to move on, “a rotational thing” assuming an average tract recovery time of 50 years, according to Winfrey. But while this specific bed hadn’t been harvested all the way to that 65 percent limit, Winfrey did describe it as “beat down pretty hard,” enough so that he’d given the divers the go-ahead to descend to 70 feet, the legal limit for shellfish harvesting, if it meant they’d find clams.

“Little slow going on the way down,” Stearns said, unzipping his wetsuit.

“Were geoducks everywhere?” asked Winfrey.

“They weren’t everywhere,” said Hozoji, facemask suction rings still fresh around her eyes. “But not hard to find.”

Hozoji, Stearns, and Winfrey make for an affable crew. Winfrey and Stearns* are two scientists who work for the tribe; Hozoji comes from an Indigenous lineage whose relationship with Pacific marine life, notably the clam, a prominent character in the Puyallup genesis story, stretches back hundreds of years and over generations of tribal struggle.

“The history of shellfish to the Puyallup is deeply important to our people, a right that our Elders fought for for over 30 years,” Danica Miller, an assistant professor of American Indian Studies at UWT, told me. (Miller, herself Puyallup, happens to be Hozoji’s cousin.)

As outlined in the Boldt Decision, the 1974 federal court ruling that upheld fishing rights for lower Coast Salish tribes, Indigenous groups and Washington state, respectively, split the total Puget Sound shellfish harvest 50-50. It is the mission of the Puyallup Shellfish Department, established in 1994, to “maximize and optimize the shellfish harvest rights secured through the [1854] Treaty of Medicine Creek,” which granted Native American tribes “the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations” in what was then the Territory of Washington. Per official Puyallup shellfish code, the Shellfish Department, of which Hozoji is an independent contractor, is “tasked with protecting the habitats and populations of shellfish,” while fostering a safe environment for tribal members to fish for ceremonial, commercial, and subsistence purposes.

Such a responsibility strikes a singular profile in someone like Hozoji, whose “heart,” she tells me, “gives a real big fuck” about restoring and protecting the Salish Sea, the delicate, low-lying Pacific Northwest marine environment, including the Puget Sound, that her ancestors have called home and subsisted on since pre-settler colonial times. If there is an afterlife and Hozoji could choose a form of reincarnation, she says she’d want to meld with the entirety of that biomass, plus that of the greater Salish Sea. “Just, like, be part of it,” she told me, “with no needs other than to feel what that feels like.”

That same ecosystem, battered as it has been by habitat loss, overfishing, and pollution, is threatened anew in a time of deregulation and rollbacks to environmental protections under Trump, on top of what’s already a grave tribal concern: global warming.

“Climate change is threatening the natural resources we have relied upon for centuries, as well as our health, economy, and infrastructure,” the 2016 Puyallup climate change report reads. “For our people, climate change is no longer a ‘tomorrow’ issue.”

After breaking down some of the 300 feet of high-pressure hose Stearns had brought along, we hunkered in the cabin. Winfrey soon turned the Monitor for shore.

A HEAVY LOAD

Hozoji, variously known among friends and colleagues as Hozi, HoHo, or the Hoz, is most widely recognized for her pummeling musical chops.

Forged over two decades of playing, recording, and touring the world in “weird rock” bands like Lozen, a drum-and-bass duo named after the legendary female Apache warrior, and the briny trio Helms Alee, Hozoji’s vocal, bass guitar, and drum stylings, in particular, are exercises in pure attack. She has earned praise from Modern Drummer and was called “a force” in the leading feminist drumming publication Tom Tom Mag.

“Her driving of her band’s songs and rhythm is propulsive, unstoppable, preternatural,” Tom Tom’s Katy Otto wrote in 2011, soon after Hozoji first started diving.

Only more recently has Hozoji begun gaining renown as an emerging scientist with a similarly preternatural gift for spotting marine life in the murkiest, most silted-up waters, a skill she honed over a six-year stint as a commercial shellfish harvester for the Puyallup.

Like many lower Coast Salish communities, Miller told me, the tribe has both specific treaty and ancestral rights when it comes to shellfish, “which necessitates Western science knowledge in addition to Puyallup ones.” (The two aren’t mutually exclusive.) Under Puyallup tribal code, commercial permits “shall be issued when the shellfish harvested will be sold, bartered, or disposed of other than for subsistence or ceremonial use.” Registered tribal members can each harvest six geoducks per day from tribal fisheries.

Hozoji says she would never begrudge any of her people those rights. And how could she?

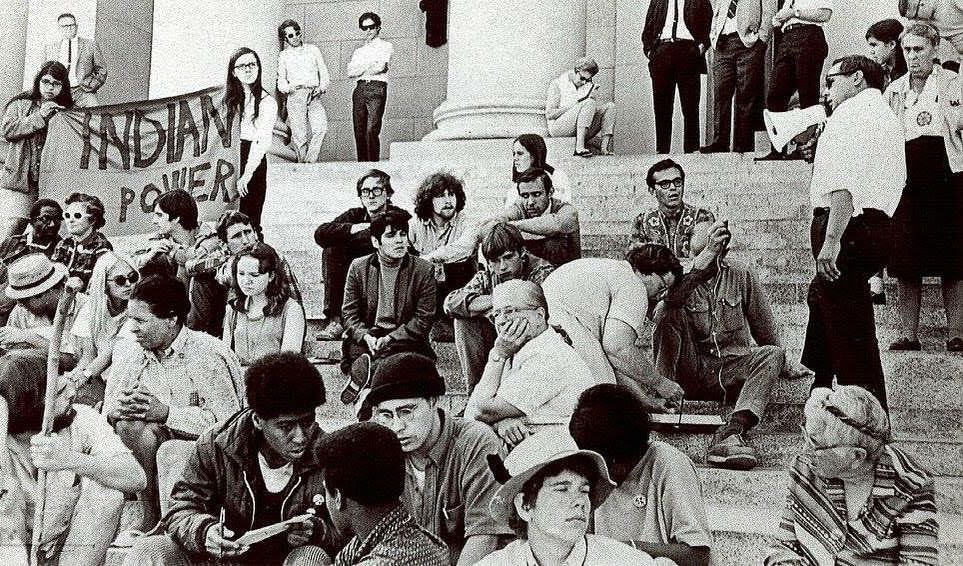

She is half Native American—Puyallup on her mother’s (Matheson) side—and comes from a long line of Indigenous conservationists. Hozoji’s grandfather (Miller’s great-uncle), Don Matheson, was “one of the primary people fighting for our fishing rights and keeping the language Lushootseed alive,” according to Miller. Hozoji’s own parents were involved in the Fish Wars of the 1960s and 70s, in which Coast Salish tribes compelled the US government, through sustained civil disobedience, to formally acknowledge native fishing rights under the 1855 Point No Point Treaty.

In other words, Hozoji carries the legacy of that multigenerational struggle. As she told me as we puttered out to the tract that morning, “so much of my life is around water.”

This could partly explain why Hozoji, over a span of years, became saddled with personal reservations when it came to her role as a commercial tribal shellfish harvester. She’s since left the harvest altogether, pivoting to immerse herself in efforts to restore the biodiversity and health of the Puget Sound and greater Salish Sea. That Hozoji was already a skilled diver with practically a sixth sense for detecting geoduck has made her sought after by crews on tribal marine conservation boats like the Monitor.

“Hozi usually does all of the digging. That’s the hard part, that takes some skill,” as Stearns told me. “She let me do it one time but then she took it away from me.”

“I let you do it twice,” Hozoji clarified.

Those underwater chops, paired with a conscious transition to doing strictly science-based diving and conservation with the Puyallup Shellfish Department, have made Hozoji equally coveted in tribe-adjacent spaces. Last year, through a grant the Puyallup gave UWT, Hozoji was tapped by Bonnie Becker, an associate professor of marine ecology. The tribe had stipulated that some of the grant be used in part to harness young American Indians in fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

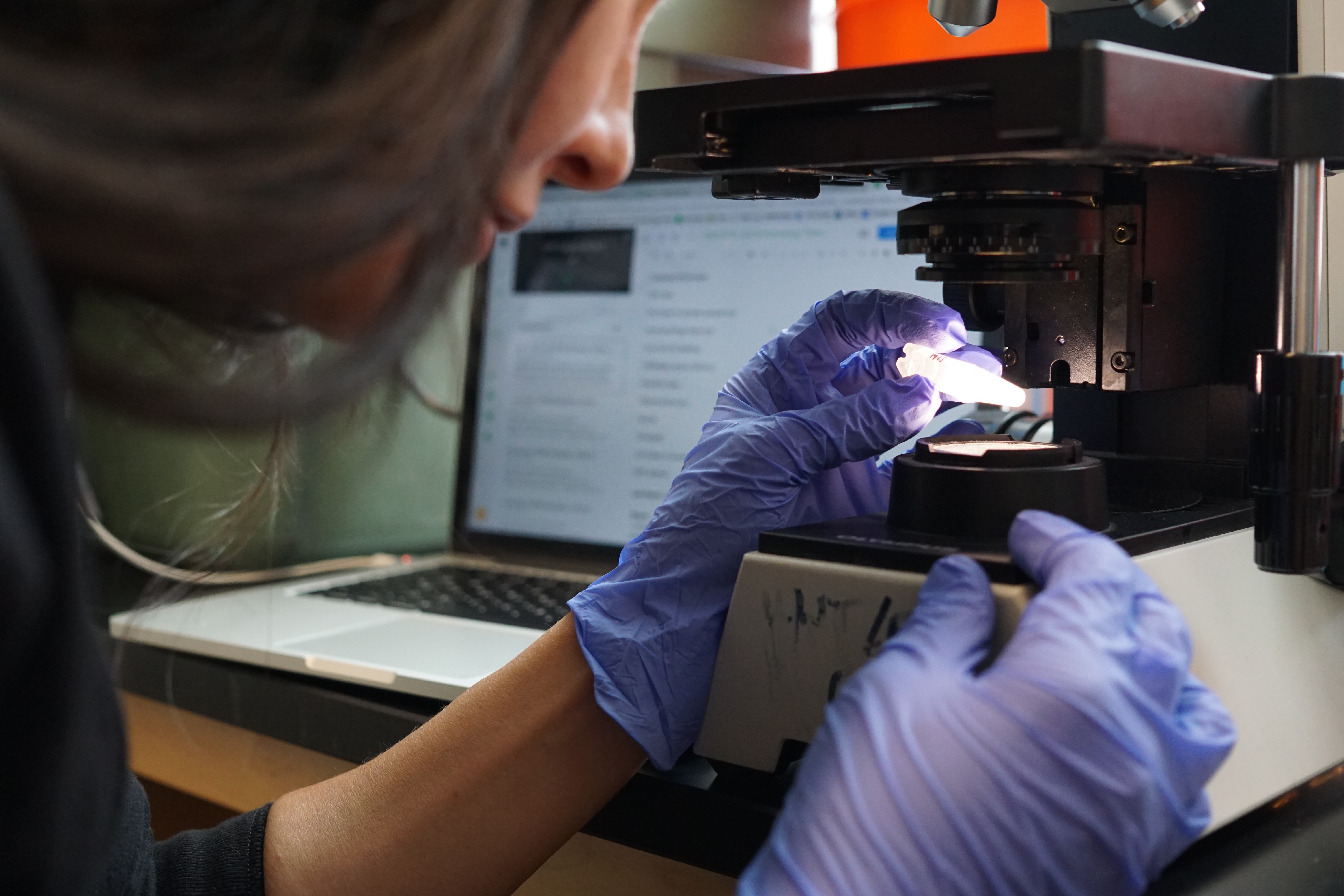

Set up in a far corner of Becker Lab, listening to D’Angelo at low volume, Hozoji offered a glimpse of what she’s been working on.

“Check this out,” Hozoji said, gesturing me in for a closer look at a vial she held up to the light. “That little speck?” she said, pointing at an individual shellfish larvae, smaller than a grain of sand, barely perceptible to the naked eye.

Part of her job is to extract that larvae, whatever kind it may be, from a slide under a microscope using a pipette. “The bitch about it is that they’re so tiny,” Hozoji said. It’s easy for shellfish larvae to get stuck in a pipette tip or in a vial, as she showed me. Other times, “even the slightest hand motion will run right through a larvae.”

Her work feeds into a restoration project aimed at the lone oyster species native to the Puget Sound. Ostrea lurida, the Olympia oyster, creates reef-like environments that perform a critical habitat-building function for other marine life, Becker explains, but the species’ population has been decimated due to ocean acidification, habitat loss, and competition and predation by invasive species. The theory Becker’s lab is testing deals with determining how many actual bivalve larvae are in a given Puget Sound water sample. And to that end, Hozoji plays an important role.

“We have come to really depend on her to do some of the more advanced work in the lab,” Becker told me. “She’s working right now on a tool”—real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), a machine-based method of counting DNA—“to help us count and identify these microscopic larvae faster and more efficiently, which is going to help us do a much better job of tracking and managing them.”

“I think if Hozoji were not a member of the Puyallup tribe she would still be a great asset to my lab because I think she has a lot of skill and talent,” Becker added. “But the fact that she does have that background and is able to connect the people who are responsible for managing the shellfish with us, who are studying the shellfish, is a really powerful partnership.”

“It is becoming increasingly clear that the only thing that will save our land for everyone is Indigenous science.”

Meanwhile, at the federal level, climate change denial is seemingly now a pillar of “America First”-style policy, despite a majority of tribal and other scientific communities believing otherwise. “The odds were already against us in our ability to do a lot of this work,” Becker said. “And this anti-science sentiment is making it a lot harder. But the changes are going to come either way.”

In this light, Hozoji’s emerging function as a link between the science establishment and Indigenous conservation falls into stark relief.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that the only thing that will save our land for everyone is Indigenous science,” said Miller, who is currently writing a history of Puyallup sovereignty that includes sections on Lushootseed language revitalization, decolonization, and shellfish. The problem, according to Miller, is that “we never see Indigenous scientists or Indigenous science validated. We [Indigenous people] all grow up fishing and hunting and caring for our land and waters in very specific ways that is certainly science,” although it isn’t described that way in Western frameworks, she said.

“There is a lot at stake here,” Miller told me. Specifically, in terms of Native American youth, validating and building on their perspectives and epistemologies will help not only the Puyallup and other Indigenous communities, but also individuals. “In the present United States, we have a 50 percent drop-out rate in the 8th grade for our Indigenous youth,” Miller said. “The suicide rate is a public health crisis. Through Indigenous STEM, we can both help our youth and planet. Pretty much a win-win.”

“Hozoji represents the privilege and burden of being American Indian in our day,” Miller added. “We have the amazing responsibility to carry on the work that our Elders have done, but at the same time, it’s a heavy load.”

To get to this point, Hozoji would first have to confront something even more primal.

II.

A HEALTHY FEAR

It was a fellow Puyallup shellfish harvester, a man Hozoji met through a cousin of hers in Idaho, who first urged Hozoji in 2009 to consider diving.

“You should sign up for the training,” the tribal harvester told Hozoji, after they had gotten to talking about the job and what it entailed. “It’s really good money and you’re an independent contractor,” he added, “so you make your own schedule.”

As a working musician who needs to make money in the stretches between touring, Hozoji liked the idea of being her own boss—and out of her element.

“Getting utterly outside of my comfort zone and into an environment that could not be more foreign than what I have grown up in and am used to,” Hozoji remembered, sounded “so otherworldly and insane to me.”

She signed up.

Outside of the preliminary scuba trainings Hozoji would go on to complete in a controlled pool setting, the final approach to her first proper Puget Sound dive, about a year later, was nerve-wracking. Dark water has always given her the creeps.

I hope I don’t freak out and embarrass myself, Hozoji thought, suited-up at boat’s edge. I hope I don’t totally lose my shit.

She took a breath and leapt in.

It wasn’t until that first open-water dive, when Hozoji was in her late 20s, that she became conscious of water as a true force of nature, though she says she’s felt pulled toward it her whole life, receiving a constant background signal from what has nearly always been lapping up against her backyard.

Some of Hozoji’s fondest childhood memories, she tells me, are rooted in the gulch between Commencement Bay, a shallow bay that’s part of Puget Sound, and her mom’s house, where Hozoji lived between the ages of 2 and 14 just outside Tacoma proper, conveniently at the opening to a foot-beaten path that connected their backyard and the water below.

Hozoji was a beach kid. And as she came of age around Commencement Bay, her enchantment with the sea and life therein only deepened.

There was the late-night brush with a bevy of otters that had come ashore to eat the fallen fruit of an apple tree near a wooden sleepover shack Hozoji and a neighborhood friend used to frequent. There was the time the two friends witnessed a lone sea lion joy-jumping across the bay at dusk—barking boof, boof, boof—on what could’ve been a Tuesday, for all Hozoji knows, although in her heart, it was a Saturday.

“That fucking sea lion is partying tonight!” she whooped.

But for every moment of awe, there was a growing undercurrent of unease. As a pre-teen, Hozoji developed what she called a “healthy fear” of the sort of murky water characteristic of an inlet like the Puget Sound. She and the same friend used to torque themselves up whenever they’d dive underwater and look at one another through goggles, spooked by the way the color seemed to drain from their faces.

“You kind of look like a dead body,” Hozoji said. “You don’t see anything until it’s right there,” staring back at you.

Jump ahead to that first proper Puget Sound dive, a critical phase of training before becoming a certified tribal shellfish harvester, and it was only natural that Hozoji agonized over the thought of buckling once in actual open water. “I was 95 percent certain I would fail miserably,” she said.

That would change in an instant.

“The very moment we went underwater, I was like”—she snaps her finger for effect—“I love this,” Hozoji said. “It was so much more beautiful and creepy-cool than I’d ever imagined. From the surface it just looks like darkness, but when you’re in it, it’s not. It’s colorful and alive and constantly moving.”

“I knew I had to be part of it forever,” Hozoji added, in the same way there was no question in her 19-year-old mind, in the afterglow of the first set she ever played at a local DIY show in her very first band, that she’d make a life performing music so long as she could.

“I’m going to do this,” Hozoji said, “until I physically cannot anymore.”

SHELL LOCK

Hozoji went geoduck digging for the first time not long after logging that initial Puget Sound dive.

It was Day One of training on Nishga Gang, the tribal vessel Hozoji harvested from for the better part of the next six years. One of the boat’s two captains, Fred Dillon, an “ultimate big brother” type, descended with Hozoji that day and pointed out what to look for while diving for shellfish: little clues that give away the location of a geoduck, like how its siphon, taking in and spitting out water, will tousle a patch of sand about the size of a cupcake top.

Hozoji watched Dillon harvest a bit, before he passed off the high-pressure hose and surfaced by himself. Now it was her turn to walk around and look for geoducks to dig and, to the mild confusion of those up-top, not say a word over the standard diver-crew comms network used on Nishga Gang. Hozoji’s silence was immediate, out of sheer instinct, she says. The tunnel vision allowed her to block out the brackishness that closed in on all sides.

“It’s freaking scary down there, especially when you’re first starting and you’re by yourself,” Hozoji said. Imagine traversing a darkened moonscape with a field of vision limited to what’s immediately before you. “It’s very, very intimidating. I think I just got in the zone.”

Huh, Hozoji thought to herself, bagging, in short order, one geoduck, then another, and another. I can do this. This is not that hard.

She surfaced about midway through the 30-minute dive, having scooped up a cool half-dozen clams.

“You gotten any?” the captains asked, expecting her to show maybe one clam for her first try.

“Oh yeah, I got some,” Hozoji replied, holding up her catch of six.

“When you dig your first geoduck, that’s a major accomplishment,” Dillon later told me. “It didn’t take Hozi long. She was able to catch on really quick.”

That the captains seemed genuinely stoked for Hozoji, impressed even, left her with a profound sense of personal triumph. Hozoji remembers the distinct rush that comes with the realization you might actually be good at a thing you didn’t think you’d be good at. She felt proud of what she’d done.

Although, as she would discover, harvesting geoducks wouldn’t always be so easy.

“You have to fight with [the geoducks] sometimes,” Hozoji told me. When one is directly under sand that is especially thick with rocks, shell fragments, and other coarse sediment, a phenomenon known as shell lock, you’re “basically jackhammering” through that tough layer with a hose to get to the geoduck. At a spot like this on the seafloor, Hozoji adds, there’s nothing you can do but hold the line until your allotted dive time runs out.

“Those days are really difficult,” Hozoji said.

That’s ultimately not what caused her to leave the Nishga Gang. That decision crystallized, rather, through a chain of events whereby Hozoji became acutely aware of the difference—the “fine line,” as Dillon called it—between exercising treaty rights as a commercial harvester, and the science she’s doing now.

“It needs to be sustainable and it needs to be respected.”

In terms of shellfish harvest management, according to Dillon, there are certain precautions the tribe takes to try to be sustainable resource managers. They’re careful not to overfish, and harvest each tract to the agreed-upon threshold (no more) before moving on. That way, he explained, each tract is given time to restore to pre-harvest levels.

“You can have all these policy and codes and laws in place, but in my view, it all boils down to enforcement,” said Dillon, who purchased Nishga Gang with his father-in-law not long before Hozoji joined in early 2011. “Without any teeth to back this stuff up, then it’s just a resource that’s going to dwindle away.”

Maybe three years in as a harvester, Hozoji said, she “started to develop a conscience about it.” This was made all the more apparent amid what she felt were shifting vibes on Nishga Gang, as a wave of new crew members joined. Hozoji, the eighth harvester to join a crew that ballooned to 18 divers, said she wasn’t seeing much basic environmental sensitivity from this diving community at the time.

“I’d see smokers flick their cigarettes off the boat into the water. Just a general sort of disregard. I don’t mean that for everyone on my boat,” Hozoji said. “There definitely were exceptions and I can’t speak for other boats because I wasn’t on them. But there was a feeling that conservation was not a topic that seemed to be on the minds of anyone.”

“I still love those dudes endlessly,” Hozoji added, speaking of Dillon and the rest of Nishga Gang’s crew. But while she “very staunchly” stands behind the right of tribal members to harvest the sea, Hozoji said, “it needs to be sustainable and it needs to be respected. And that’s the shit I started to feel uncomfortable with.”

In the meantime, mechanical errors didn’t help her mood. She blamed these slip-ups, in part, on a rapidly expanding crew under a lot of pressure to perform.

In the fall of 2015, Hozoji and a fellow Nishga Gang diver were hospitalized for carbon monoxide exposure after they both vomited after surfacing. Another close shave earlier that year involved a face mask shared among the boat’s dive team. Hozoji claims the mask hadn’t been sufficiently cleaned before one of her dives and that this led to the mask’s regulator getting stuck open, hemorrhaging free-flowing air from an onboard generator with a limited supply of oxygen. Hozoji was 60 feet underwater, solo. Between the scuba gear and about 70 pounds of geoducks lashed around her waist, she had roughly 150 extra pounds strapped to her body. She went to roll the regulator back, attempting to free it from being locked open, only to find it was stuck shut.

Water started filling the mask, up over Hozoji’s nose, then her eyes, when everything went white.

“I stood up and did the motions that it requires to try and remove water from your mask if it’s flooded,” Hozoji said. “Luckily it worked.”

She finished the dive.

“We’re the kind of boat where it’s safety first,” Dillon told me. Despite this, every diver on that boat, according to him, goes through at least one test of mettle in the harsh, at times unpredictable realms of deep digging. It’s just the nature of the work.

“There’s a lot of danger in what we do,” Dillon said. And the reality is, “sometimes things get gunked up.” That is, sometimes grit finds its way into your underwater breathing apparatus and your face mask, as Dillon described it, starts to “sweat.”

To Dillon, Hozoji’s whiteout incident seemed less a matter of negligence than an honest oversight. He emphasized the day-to-day upkeep required of a suite of filters, pressure-relief valves, and assorted components that comprise a working dive kit on a tribal harvest boat, not to mention the number of divers using that same shared kit.

The fact that Hozoji knew how to pull herself out of the situation speaks to the sort of hands-on training and mentorship Dillon says has always been the Nishga Gang way. It’s also what sets apart a diver like Hozoji. A dangerous diver, according to Dillon, is a scared diver, a timid diver. Not necessarily someone who would’ve kept their composure.

The carbon monoxide incident is harder to explain. Dillon says it remains the first and only time something like it has gone down on Nishga Gang.

As Hozoji and her dive partner descended that day, Dillon remembers, there was no wind. “So we’re thinking maybe the exhaust from the main engine got up in the intake of the air compressor” and didn’t get filtered out to the extent it needed to, he told me. “It’s kind of crazy, but that’s what we’re assuming happened,” he added, “because we had it tested out and everything. Our filters, everything was good. The air quality was good.”

It was, simply, a “mishap,” Dillon said. “But thank goodness Hozoji came to and everything was fine after that.”

The pivotal incident, the moment Hozoji knew she had to leave the harvest for good, was when she witnessed nudibranchs—gastropod molluscs, better known as sea slugs—mating en masse in Puget Sound in the spring of 2015.

“They’re just piled on top of each other, humping,” Hozoji told me, laughing. “Fields of them. They’re beautiful creatures, super fragile, gorgeous. And they’re there to perpetuate their species, you know?”

By this point, Hozoji had begun doing survey dives with Dave Winfrey, the Puyallup shellfish biologist, who she already knew as the guy who assigned permits to “legit” divers on behalf of the Shellfish Department. Hozoji had explained to Winfrey, who’d asked Hozoji to work with him and his team because their other contractor at the time was overbooked, that she was coming to realize marine conservation and science were more in line with her interests.

“If you ever need some muscle on your side,” Hozoji offered Winfrey, “I’d love to be involved.”

For the next three years, she’d moonlight as a shellfish tract surveyor under Winfrey’s tutelage part-time between April and October, while harvesting year-round on Nishga Gang. The more surveys Hozoji helped out on, she says, the queasier she felt, like that day at the nudibranch mating grounds, which happened to overlap with a geoduck tract.

“We’re surveying it,” Hozoji remembered, “and I’m thinking to myself about how we’d finish the survey and say ‘yes, it’s OK for people to come here and dig geoducks’ and that’s going to mean that all of these boats are going to drop anchor here. They’re just gonna harvest right through the nudibranchs.”

“That felt real bad to me,” she said.

A couple of months later, Hozoji found herself harvesting geoducks near the site of that very sea slug orgy. Not the exact spot, but close enough that she was unable to shake the fact that she had facilitated the unintentional slaughter of no small number of nudibranchs. While there was no way of telling for sure, Hozoji knew right then she had to walk away from the harvest for good.

“I thought about it long and hard, cried a million tears, and felt real conflicted,” Hozoji said. “I couldn’t say that other people shouldn’t.”

Recuperating at home one day in late 2016, Hozoji sat with Dillon. And she quit.

“It’s all good, you know?” Dillon told me. “We definitely don’t force someone to do something they don’t want to do, especially out there.”

As a harvester who also works as a natural resources policy representative for the Puyallup’s shellfish commission, Dillon says he could feel for Hozoji.

“I’ve always known Hozi to be more of a giving kind of person instead of a taking kind of person,” Dillon said. “I couldn’t say anything bad about her. She’s a good person inside and out. She has a big heart. She wants to save things.”

EVERYTHING EATS EVERYTHING

Hozoji heard from Bonnie Becker a few months later.

“I do a lot of work with people who work for tribes because of that shellfish connection,” said Becker, who had put a call out to various contacts and friends in her network last year after speaking with Danica Miller.

Miller was in charge of the Puyallup tribal grant given to UWT, dedicated in part to assist recruiting tribal members into the sciences. Miller had reached out to Becker, who suggested funding Indigenous students in Becker Lab: specifically, bringing a non-college student in to do lab work as a way of setting that person on course for a degree.

“This seemed like a perfect fit and I agreed,” Miller later told me. She would describe Hozoji as “a perfect example of a Puyallup who both understands Puyallup science and is able to bridge that with Western methods.”

That’s partly why Becker had Hozoji working specifically on qPCR, the machine-based DNA counting method, as Becker hopes the technique will be of use to tribal shellfish biologists in their ability to manage such resources. Becker has come to depend on Hozoji’s “meticulous way of working,” as Becker described it, because “we have to know what we have to create a tool that we can then apply on what we don’t already know.”

Seated at her far-corner station in Becker Lab, as D’Angelo rolled into the latest Dale Crover (Melvins/Nirvana) solo record, Hozoji tapped out a little drum fill on her knees in the empty moments it took for the ethanol to settle on one of her slides. The physical, exacting nature of the work requires good, old fashioned patience. You get a little antsy sometimes.

“Counting microscopic larvae by hand is an extremely slow process,” Hozoji said. “So it was like, cool, this might be a way to have it done in seconds, rather than weeks or months.”

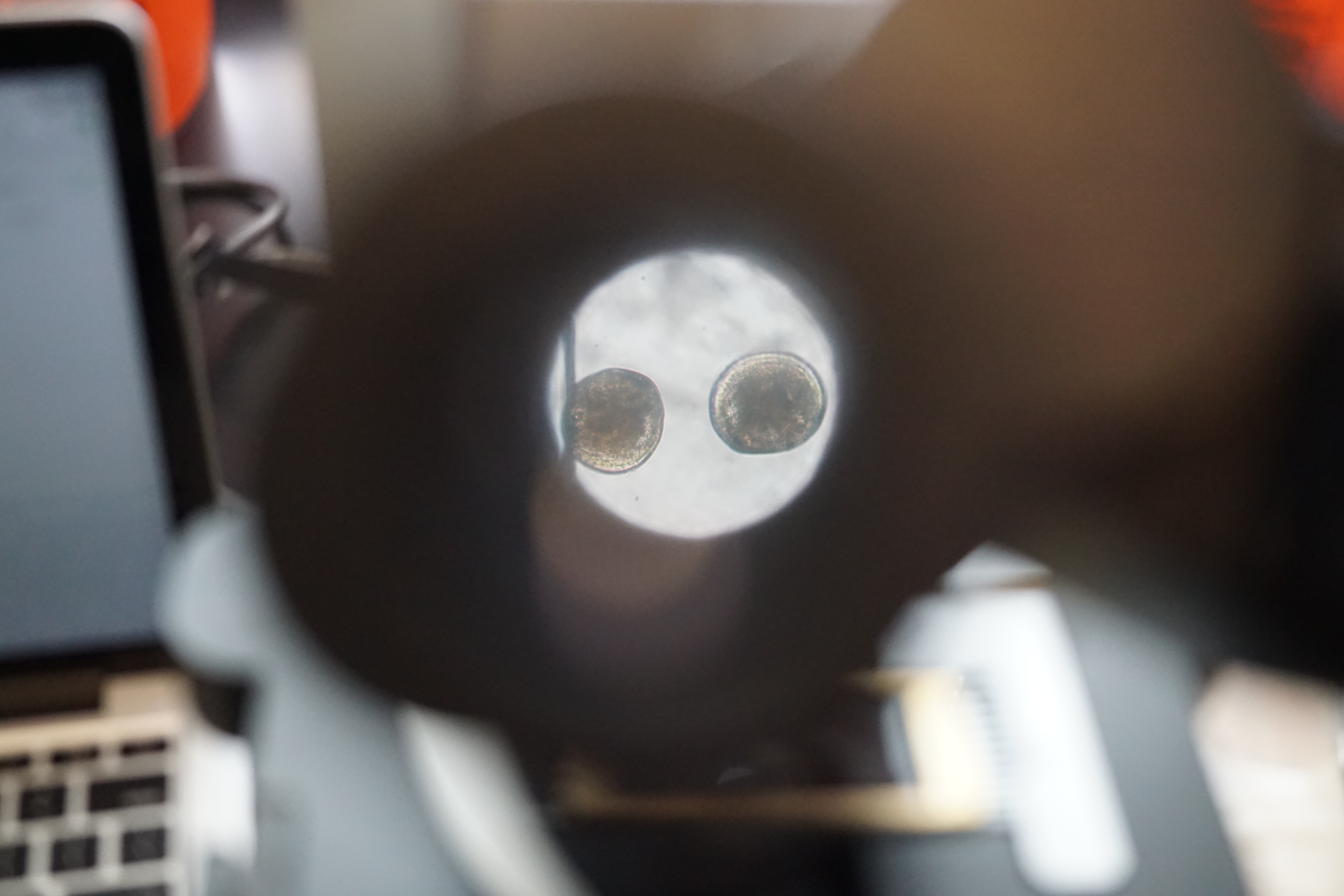

“And so, these are wild,” she told me, gesturing to a grip of Puget Sound water samples resting in a vial rack, representing the past couple of months of her work. “I’ve gone through and separated them into these individual vials. This one”— she points to one of the vials—“has one large clam, what I would assume is a geoduck in it. This one here”—points to another—“has five big Olympia oyster larvae.”

It’s a matter of going through, Hozoji explained, so that when the time comes to begin testing with the qPCR machine, they will know if there is, say, five in each vial. As they explore whether or not they can accurately use qPCR to count wild larvae in a lab, if the qPCR machine reads “100” then they will know it’s registering bits of DNA that have either broken off from larvae or were in the water column to begin with. “And if that is the result, we know it’s counting stuff that isn’t just larvae,” Hozoji said. “And we know we can’t use it as a reliable source for counting larvae specifically.”

I asked Hozoji if she had spent much time looking down a microscope prior to this.

“Zero,” she said. “I mean, science class in high school. But other than that no, not at all. I always thought it was neat or whatever, but never saw myself ending up [doing] something like this.”

“I’m like a little kid going into this,” Hozoji added. “I’m a romantic.”

She has come to appreciate the symmetry of an Olympia oyster larvae under a polarized microscope. In particular, the way that causes the bivalve shell to create an X shape, which then helps narrow down her search while sifting through a Puget Sound water sample “filled with other gunk.” As a self-diagnosed germaphobe, she has also made peace with the fact that she has surely swallowed tons of the bivalve larvae she handles here in Becker Lab. “I can’t even imagine how many,” she said.

“Getting to look at these through a microscope and imagine their existence is just…” Hozoji said, struggling to find the word.

Getting to be so up-close and hands on, getting to be around water, she says, opens up space for her to think about the great continuum of things. About her place in the Universe and on Earth, in the past, present, and future of her tribe and this region she calls home.

“Everything eats everything,” Hozoji said. “So, save the whales? Hell yeah, save the whales. But that means save the oyster larvae, too. Everything is important.”

Hozoji messaged me a few days after my visit.

“I’m here staring through the microscope at Becker Lab and something occurred to me,” Hozoji wrote. “Which is simply that there is so much more to life than the stuff we see and think and worry about everyday. In the same vein [as] knowing that the underwater world is always there and how that is a comfort to me when I’m freakin’ out about humanity, looking at life at a microscopic level calms me because it reminds me that there is a lot more shit going on than what is visible from my human perspective.”

What’s down there?

THE REST OF THE WORLD OUT THERE

Back on the Monitor, returning to Shellfish Department headquarters, Hozoji’s dozen-geoduck haul was spot-checked, stowed, and bound for the lab. The biotoxin results for red tide testing typically are ready in 24 to 48 hours. (This batch of geoducks was biotoxin free.)

Before we pulled into the slip, Winfrey veered in for a closer look at something, just a speck when Hozoji first pointed it out at the edge of Commencement Bay. It was the small brown beach shack Hozoji and her friend spent so much time in coming up, where Hozoji developed her healthy fear of murky water.

The wooden structure appeared dilapidated, eaten away by years of saltwater and wind. But it was still standing.

That afternoon, rinsing down her wetsuit in the backyard of her youth, Hozoji told me about how she’s since moved back into the same modest, wood-panelled home she grew up in. The move came at the urging of her mother after the apartment Hozoji and one of her two current roommates had been living in, in Tacoma proper, flooded with sewage. Hozoji’s drums, the same Rogers kit she’s been playing since she was 15, survived.

Behind the house, the foot-beaten path she took as a kid had fallen into disuse, gradually taken back by nature. The gulch itself, Hozoji later wrote me, “has been slowly but surely sucking the hillside into its mouth for as long as I’ve been alive to observe it.” Trees that used to be in the middle of their yard, she added, are now part way down the hill.

At some point, Hozoji’s mother had the property placed into the tribal land Trust. If something ever happens to Hozoji—“if I die,” she said—the land will go back to the Puyallup.

Later, seated at the kitchen table, Hozoji showed me a pocket-sized, silver booklet that she often carries. It was a gift from her roommates, Hozoji explains, who made it for her. The pages within, they write by way of introduction, include “some great women who have made history in marine biology, diving, and oceanography.”

The entries are brief, handwritten, and begin in the 19th century, with black and white photos pasted alongside each of the 20 or so names. There’s Myrtle Elizabeth Johnson (1881-1967), who wrote “Seashore Animals of the Pacific Coast”; Roger Arliner Young (1889-1964), the first African American woman to receive a PhD in zoology; “The first lady of Limu,” Isabella Abbott (1919-2010), discoverer of over 200 kinds of algae; and “Her deepness” Sylvia Earle (1935-present), the first female chief scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, among others.

“This is only a slice of the rich contribution women have made,” her roommates add. “But we hope it will serve as inspiration as you begin your journey in marine biology.”

The final entry in the booklet is reserved for their friend, Hozoji.

Beginning this fall Hozoji will start classes at UWT, working toward a bachelor’s degree in marine biology. If it is not about how deep you dig, it’s that you keep digging.

“I feel 100 percent inspired and excited about our Indigenous youth,” as Miller told me. “It’s the rest of the world out there that gives me worry.”

Hozoji, for her part, is also under no illusions.

“I’ve thought many times about what kinds of challenges I will face once I become more heavily involved,” Hozoji said. “I’m signing on for a lot of struggle.”

“The idea to me,” she went on, “is like, I’m going to help protect this thing that I love that is so beautiful and fragile. I’ll be able to get in people’s brains and help them understand why they should care about this sort of thing.”

“I also know there are plenty of people who just do not give a fuck,” Hozoji said. “But ultimately I think there is a reason to be trying. You’ve got to create a balance because otherwise those people win.”

*A previous version of this story misidentified Winfrey and Stearns as Puyallup tribal members. They are neither Puyallup members nor native people. The story has been changed to reflect that distinction.

More

From VICE

-

Juan Ocampo/NHLI/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Borealys Games -

Illustration by Reesa -

Illustration by Reesa