Amazon has sold cheap facial-recognition software to law enforcement agencies in at least two states and has also sold it to a police body camera manufacturer and a company that does intelligence and data analysis for law enforcement, according to internal documents at those police departments and Amazon’s own marketing materials.

The software, created by Amazon Web Services, is called “Amazon Rekognition” and promises to “perform real-time recognition of persons of interest from camera live streams against your private database of face metadata,” according to the company’s marketing materials. The software uses image recognition algorithms to track and identify objects in people when tested against an existing database of videos or photos.

Videos by VICE

The software was created last year, but new documents obtained using freedom of information requests by the American Civil Liberties Union shows how it’s currently being used by police, how they hope to use it in the future, and reveal that federal data fusion centers are interested in the technology.

These law enforcement uses of Rekognition signal that Amazon, one of the world’s most powerful companies, has entered the law enforcement surveillance market in earnest.

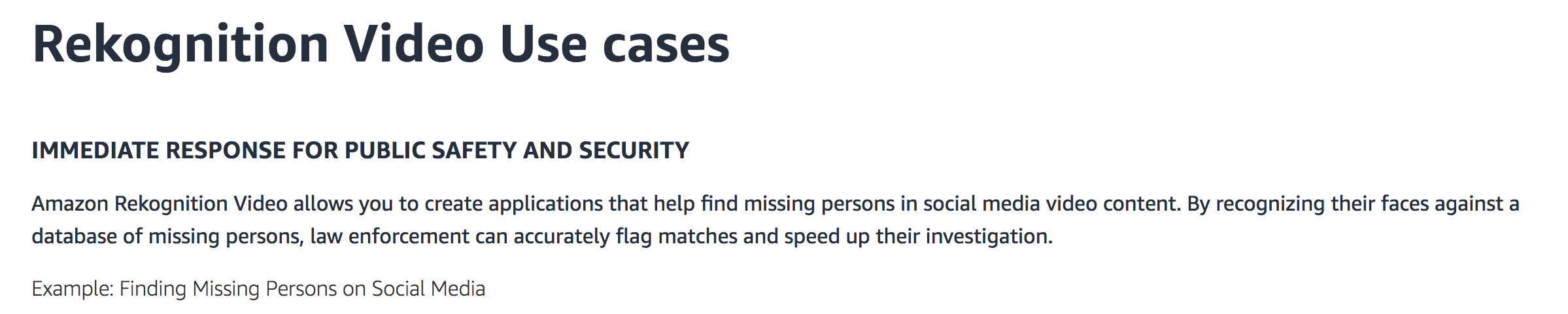

At the company’s AWS Summit in Seoul, South Korea last month, Ranju Das, the director of Rekognition, said that the Orlando, Florida police department is a “launch partner” for the technology.

“It’s a smart city, they have cameras all over the city,” Das said. “The authorized cameras are then streaming the data to [Amazon] … we analyze the video in real time, search against the collection of faces that they have,” he said, adding that the technology could be used to track the whereabouts of the city’s major and “persons of interest” and that the system could send real-time alerts to the police.

A spokesperson for the Orlando Police Department told me that it is only piloting the technology and that it “is not using the technology in an investigative capacity or in any public spaces at this time.”

The Rekognition website and its partnership with police body camera manufacturer Body Worn suggest that Amazon and law enforcement have interest in identifying people in real time while in the field. It’s worth noting that Amazon has changed an example use case on its website from “Example: Public safety – law enforcement body cams” to “Example: Finding missing persons on social media.”

Amazon also says it sells the software to Data Fusion Systems, a company whose “goal is to provide actionable intelligence to authorities.”

“Amazon’s marketing materials read like a user manual for authoritarian surveillance,” Matt Cagle, a technology and civil liberties attorney at the ACLU of Northern California, told me on a phone call. “Amazon has recommended Rekognition for officer body cameras, which would transform them from a tool for officer accountability into surveillance machines pointed at the public.”

A spokesperson for AWS told me in an emailed statement that “Amazon requires that customers comply with the law and be responsible when they use AWS services. When we find that AWS services are being abused by a customer, we suspend that customer’s right to use our services.”

Rekognition in use

It wasn’t a secret that police departments were interested and had purchased this technology—local news reports in Washington County, Oregon, showed that the sheriff’s office there purchased and is using the technology; Orlando’s interest has also been previously reported, and Amazon advertises both cities as customers.

However, emails, presentations, contracts, and other Rekognition-related documents obtained by the ACLU from the two departments show that the software is inexpensive and already has interest from federal data fusion centers, which aggregate data across jurisdictions and departments and are seen as a nightmare for civil liberties.

“This is all happening at a time when public protest is at an all-time high and the federal government is attacking immigrants and labeling black activists as criminals,” Cagle said.

The Washington County documents show that the department spent $400 to upload a database of 305,000 mugshot photos dating back to 2001 to Amazon’s servers. It pays roughly $6 per month to use the software, which matches that database against people who are suspected of committing crimes: “We only use it when we’re investigating criminal activity when we have a suspect in a crime,” Jeff Talbot, a public information officer for the department, told me on the phone. “We are not using it to surveil people or doing real-time surveillance … there have been discussions and we’ve drafted policies to prohibit anything further than what we are doing right now.”

“We are not trying to hide that we’re doing this, we are proud of this software,” Talbot added. “It’s finding innovative ways to keep people in our community safe.”

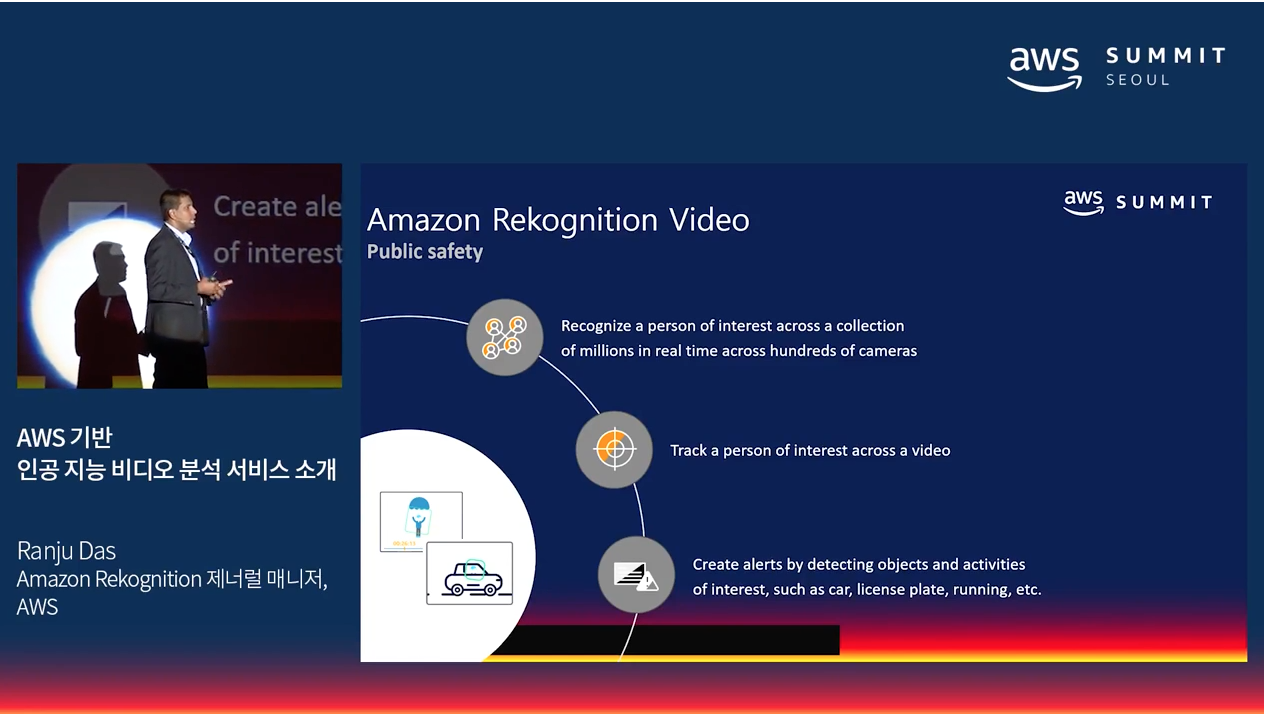

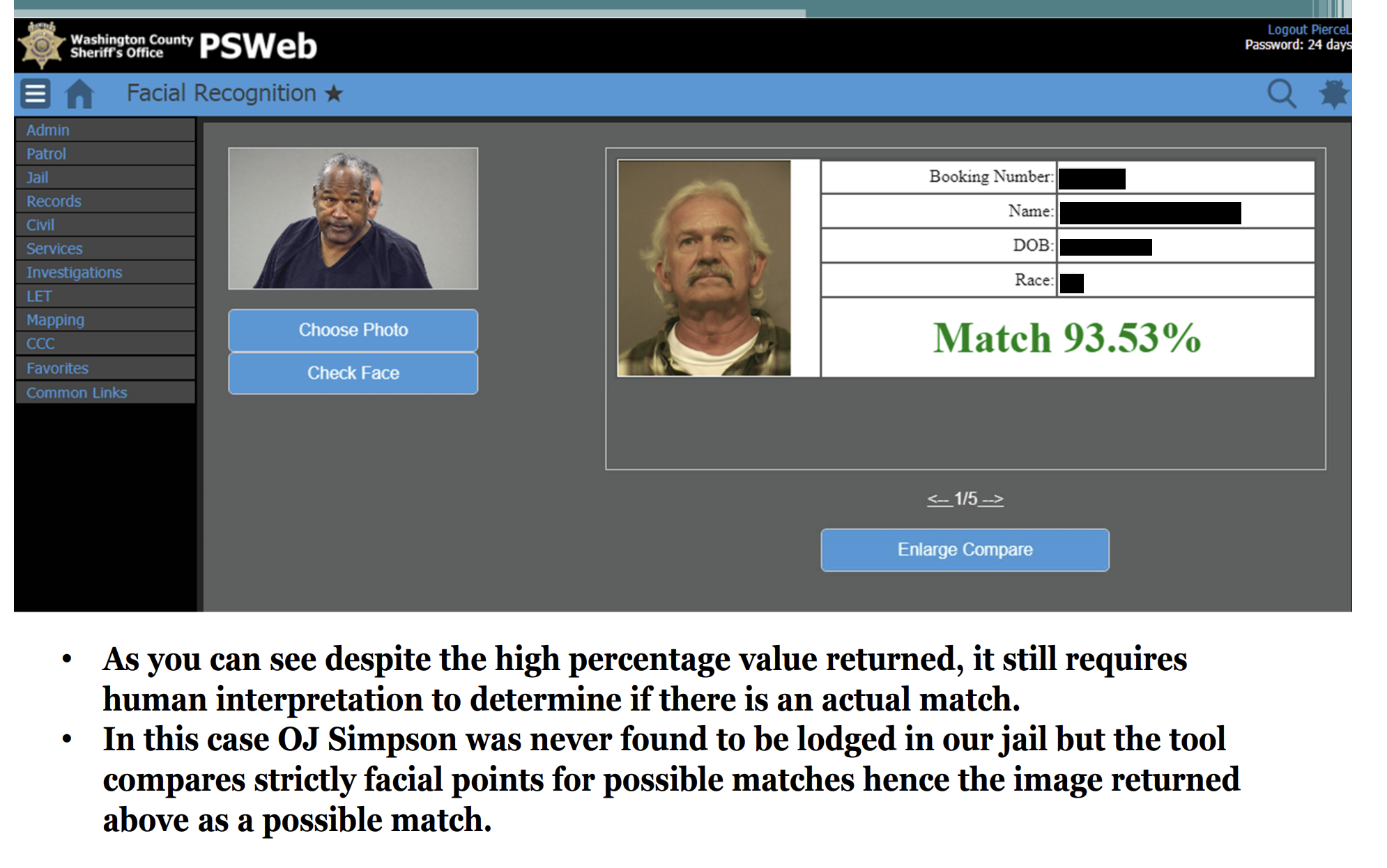

But a training presentation obtained by the ACLU shows that the service can have false positives. A slide in the presentation showed an instance where someone was identified as a 94.66 percent match against an existing photo, but wasn’t the correct person. Another slide shows an image of OJ Simpson was a 95.53 percent match with a white man with a mustache and long white hair.

“I am hoping to expand our backend of images to every law enforcement agency in the metro Portland area. And possibly even to all of Oregon and beyond,” Chris Adzima, a senior informations systems analyst for the Washington County Sheriff wrote in an email to Amazon.

Adzima wrote a testimonial blog post for Amazon in June, 2017 in which he said he used the software to identify a man who had shoplifted from a hardware store based on the store’s surveillance footage. Emails sent between Adzima and Amazon show that Amazon coached Adzima in writing that blog post.

“We shifted the narrative voice within the walk-through from I to We,” an Amazon employee wrote to him in one email about the blog post. “This was at the request of the account team that didn’t want to make it sound like you’re a lone wolf programmer working on AWS (it might be true, but that’s not the impression they want.)”

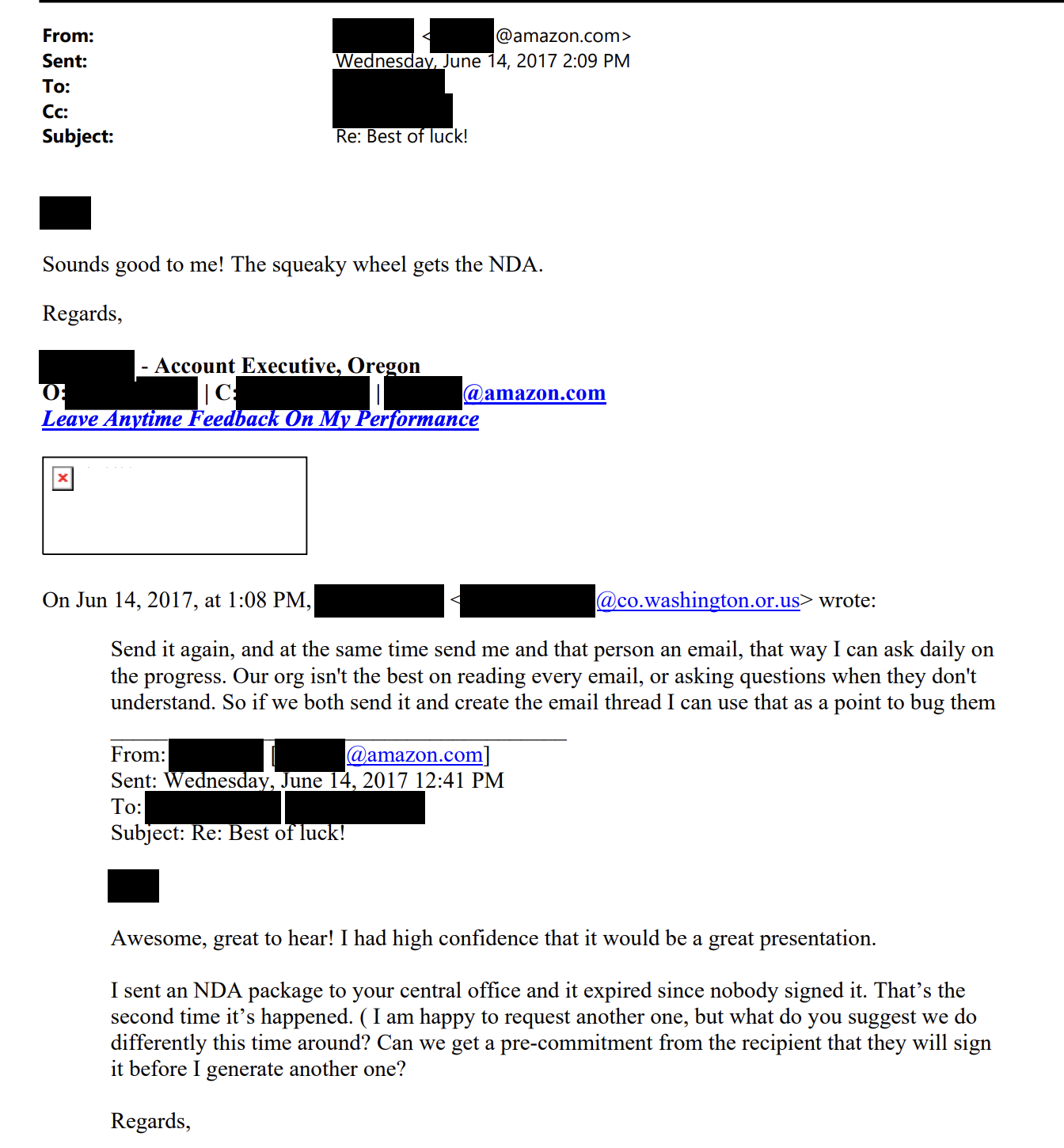

Amazon also asked the department to sign a nondisclosure agreement about Rekognition, which is a common practice in the surveillance tech industry. For example, Harris Corp. requires law enforcement agencies to sign NDAs for its cell-site simulator StingRay technology, which is widely used by police to track cell phones. Washington County didn’t sign Amazon’s NDA right away, and an Amazon employee followed up with Adzima several times; Adzima eventually assured the employee that he would make sure it got signed.

“Sounds good to me!,” the employee responded. “The squeaky wheel gets the NDA.”

Cagle said that “the public has a right to know when law enforcement agencies are seeking to acquire or use surveillance technology, which includes facial recognition.”

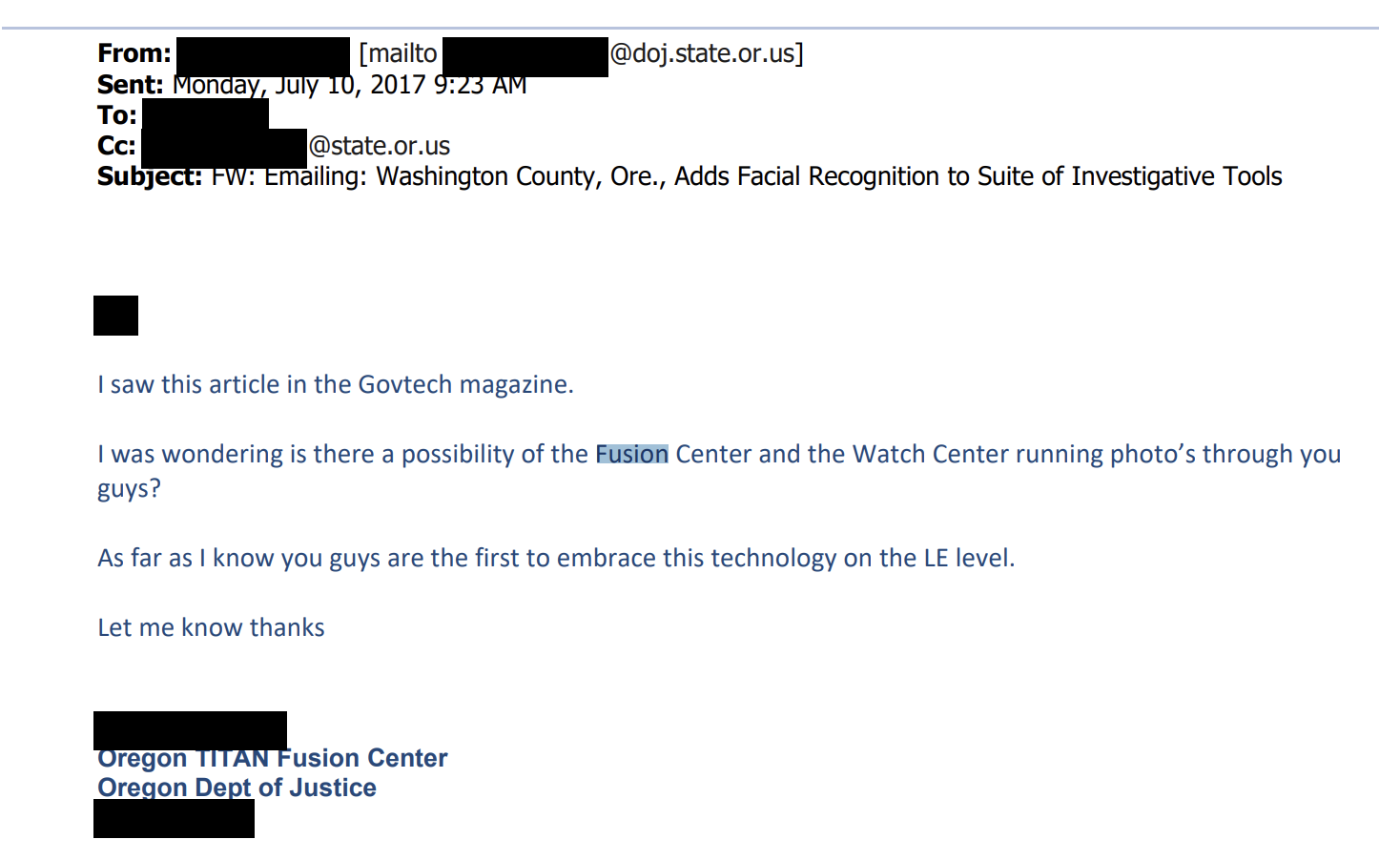

The emails also show that an official with the Oregon TITAN Fusion Center reached out to Adzima after Government Technology magazine wrote an article about Rekognition.

“I was wondering is there a possibility of the Fusion Center and the Watch Center running photos through you guys?” the official wrote. “As far as I know you guys are the first to embrace this technology on the LE [law enforcement] level.”

Fusion centers were started soon after 9/11 as a means of aggregating local, state, federal, and private-sector data. The data can come from traffic records, schools, ISPs and telecom companies, banks, public records, law enforcement, and more. According to its website, the Oregon TITAN Fusion Center is run by “the Oregon Department of Justice, Oregon State Police, Oregon State Sheriff’s Association, the Oregon Association of Chiefs of Police, Oregon District Attorney’s Association, Department of Homeland Security, Salem Police Department, and the FBI.”

Rekognition currently runs images and video against only images that individual law enforcement agencies upload to their own AWS clouds, but if fusion centers were to upload their own aggregated data to AWS cloud services, the power and breadth of its matching database would far exceed that of any individual police department.

The ACLU and dozens of other civil liberties groups—including Human Rights Watch, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, Muslim Justice League, WITNESS, Demand Progress Action, and CAIR—wrote a letter to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos urging him to stop selling Rekognition to law enforcement.

“People should be free to walk down the street without being watched by the government,” the letter says. “Facial recognition in American communities threatens this freedom. In overpoliced communities of color, it could effectively eliminate it.”

Amazon, for its part, said that it is proud of Rekognition and believes that it makes the world a better place, saying that the technology could be used to help identify missing persons.

“As a technology, Amazon Rekognition has many useful applications in the real world (e.g. various agencies have used Rekognition to find abducted people, amusement parks use Rekognition to find lost children, the Royal Wedding that just occurred this past weekend used Rekognition to identify wedding attendees, etc.),” the company said. “Our quality of life would be much worse today if we outlawed new technology because some people could choose to abuse the technology. Imagine if customers couldn’t buy a computer because it was possible to use that computer for illegal purposes?”

More

From VICE

-

Simone Joyner/Getty Images -

Youth Code -

Screenshot: Remedy Entertainment -

Screenshot: HypeTrain Digital