Image: NASA

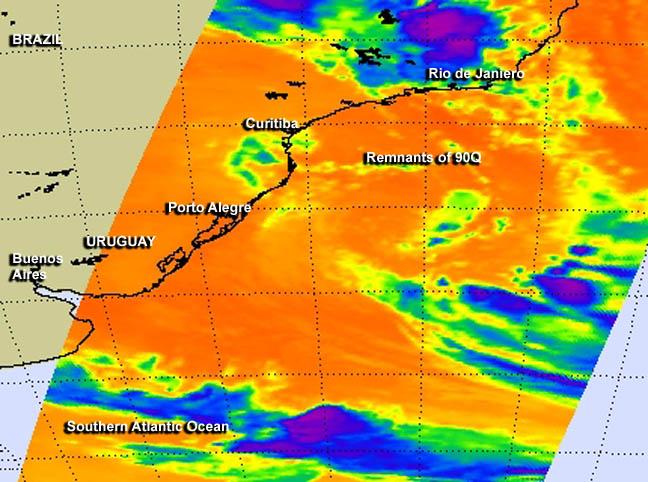

The tropical storm known impersonally as 90Q died barely a day after it was born. By Friday, NASA's Aqua satellite was registering barely an unsettled fizzle of atmospheric convection off the coast of Brazil, while the cold cloud-top temperatures indicative of severe weather had dwindled to a patch near the storm's center of circulation.With its short life spent spinning in the southern Atlantic Ocean about due south of Sao Paulo, it's mostly surprising that 90Q existed at all. While tropical storms skip across the Pacific and Indian oceans with clockwork regularity, and northern Atlantic hurricanes average six or so annually (10.1, including non-hurricane named tropical storms), the southern Atlantic latitudes don't see much of anything at all. 90Q is only the third southern Atlantic tropical or subtropical storm since 2004, following 90Q in 2010 (same name, different storm) and the hurricane/cyclone Catarina in 2004, which actually made landfall, causing intense flooding and killing at least three.90Q didn't have much of a chance really, despite having a supply of relatively warm water to feed on. For a tropical storm, the southern Atlantic isn't a terribly hospitable place.In 1968, a sailor named Donald Crowhurst was at the tail end of a bizarre and elaborate deception. An underskilled, under-equipped competitor in the Sunday Times Golden Globe yacht race, a solo round-the-world competition mostly taking place in the lower latitudes, from the southern Atlantic to the rabid, frigid Southern Ocean and back up through the Atlantic, finishing in the UK. Crowhurst didn't stand a chance.So, he fudged, lying about his positions over the course of many months, while never leaving the southern Atlantic. In essence, he hid out near the starting line, waiting for the other competitors to enter the home stretch so he could jump out at the last moment. But it didn't work out like that; Crowhurst attempted to jump out, but he was stymied by a notorious region of the Atlantic Ocean known as the doldrums, or, properly, the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Here, the weather becomes a bizarre region of stagnant non-weather alternating with intense, violent localized thunderstorms. A sort of hell.As the story goes, adrift and paranoid, Crowhurst lost it, trapped in his own lie that had become a physical manifestation of flat water and stagnant air. He never radioed for help and his writings, recovered later with his mostly intact sailboat, became increasingly psychotic. He committed suicide, it's thought, stepping off his boat and drowning.

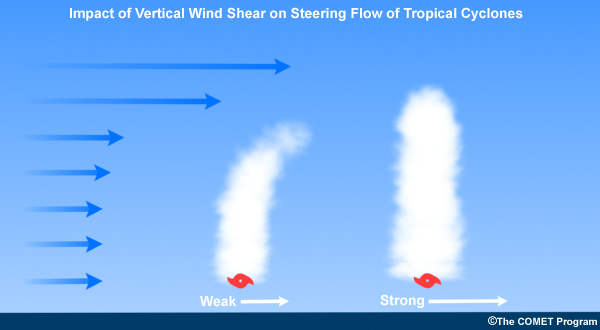

90Q is only the third southern Atlantic tropical or subtropical storm since 2004, following 90Q in 2010 (same name, different storm) and the hurricane/cyclone Catarina in 2004, which actually made landfall, causing intense flooding and killing at least three.90Q didn't have much of a chance really, despite having a supply of relatively warm water to feed on. For a tropical storm, the southern Atlantic isn't a terribly hospitable place.In 1968, a sailor named Donald Crowhurst was at the tail end of a bizarre and elaborate deception. An underskilled, under-equipped competitor in the Sunday Times Golden Globe yacht race, a solo round-the-world competition mostly taking place in the lower latitudes, from the southern Atlantic to the rabid, frigid Southern Ocean and back up through the Atlantic, finishing in the UK. Crowhurst didn't stand a chance.So, he fudged, lying about his positions over the course of many months, while never leaving the southern Atlantic. In essence, he hid out near the starting line, waiting for the other competitors to enter the home stretch so he could jump out at the last moment. But it didn't work out like that; Crowhurst attempted to jump out, but he was stymied by a notorious region of the Atlantic Ocean known as the doldrums, or, properly, the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Here, the weather becomes a bizarre region of stagnant non-weather alternating with intense, violent localized thunderstorms. A sort of hell.As the story goes, adrift and paranoid, Crowhurst lost it, trapped in his own lie that had become a physical manifestation of flat water and stagnant air. He never radioed for help and his writings, recovered later with his mostly intact sailboat, became increasingly psychotic. He committed suicide, it's thought, stepping off his boat and drowning. The doldrums are indeed a place to go mad. It's here, along the equator near the waistline of the Atlantic Ocean, that the northeast and southeast trade winds collide. As these patterns of surface air movement meet, they shoot upwards, leaving a band of low pressure known as a trough or anticyclone, where moisture is sucked upwards and spun outwards. Air masses here move vertically and are often extreme. It's thought that this weather pattern is what brought Air France Flight 447 down: a powerful slab of rising air.But at the surface, there's nothing, save for regular albeit very brief squalls. The seasonal northward movement of the ICTV is what dictates hurricane season for the eastern United States, as the zone turns into a kind of storm factory, occasionally spinning off a thunderstorm that will go on to grow up to be a full-on hurricane. No such luck for the southern Atlantic, as this storm factory migrates in the opposite direction.Meanwhile, the storms that are produced are usually ripped to shreds just as quickly by strong vertical wind shear in the troposphere, as below.

The doldrums are indeed a place to go mad. It's here, along the equator near the waistline of the Atlantic Ocean, that the northeast and southeast trade winds collide. As these patterns of surface air movement meet, they shoot upwards, leaving a band of low pressure known as a trough or anticyclone, where moisture is sucked upwards and spun outwards. Air masses here move vertically and are often extreme. It's thought that this weather pattern is what brought Air France Flight 447 down: a powerful slab of rising air.But at the surface, there's nothing, save for regular albeit very brief squalls. The seasonal northward movement of the ICTV is what dictates hurricane season for the eastern United States, as the zone turns into a kind of storm factory, occasionally spinning off a thunderstorm that will go on to grow up to be a full-on hurricane. No such luck for the southern Atlantic, as this storm factory migrates in the opposite direction.Meanwhile, the storms that are produced are usually ripped to shreds just as quickly by strong vertical wind shear in the troposphere, as below. To put the rarity of southern storms into perspective, try this. Note the solitary squiggle off the coast of Brazil for 2004's Catalina.

To put the rarity of southern storms into perspective, try this. Note the solitary squiggle off the coast of Brazil for 2004's Catalina. What climate change means for the lower latitudes and cyclonic activity is mostly unknown. Jeff Masters notes at Weather Underground that 90Q formed with oceanic water temperatures a touch below normal, while 2004's storm occurred with slightly above average water temps. The primary destroyer of the storms that do generate in the region is vertical wind-shear and how water temperature might influence that is not very well studied. Warmer water could make a difference in ideal conditions, but water temperature is not a very significant limiting factor in southern Atlantic storm production.So, maybe? It's not hard to find people more willing to speculate. The recent storms in the area are few and far between, but, until 2004, it was usually considered to be more or less impossible for a hurricane to even happen. And yet: Here we are.

What climate change means for the lower latitudes and cyclonic activity is mostly unknown. Jeff Masters notes at Weather Underground that 90Q formed with oceanic water temperatures a touch below normal, while 2004's storm occurred with slightly above average water temps. The primary destroyer of the storms that do generate in the region is vertical wind-shear and how water temperature might influence that is not very well studied. Warmer water could make a difference in ideal conditions, but water temperature is not a very significant limiting factor in southern Atlantic storm production.So, maybe? It's not hard to find people more willing to speculate. The recent storms in the area are few and far between, but, until 2004, it was usually considered to be more or less impossible for a hurricane to even happen. And yet: Here we are.

Advertisement

What's different about the southern Atlantic?

Advertisement

Advertisement