The 1962 "Sedan" nuclear test, part of Operation Plowshare, displaced 12 million tons of earth and created a crater 320 feet deep and 1,280 feet wide. Image: National Nuclear Security Administration.

oThe nuclear bomb has been detonated over 2,000 times since the start of the Cold War, but it was used on people only twice. This week marks 67 years since the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The combined death toll of the two cities reached between 150,000 and 250,000 within a few months, while the world was introduced to the specter of nuclear war, which has since faded but will never disappear. Despite that, some scientists and politicians tried to find something redemptive in the most powerful weapons ever built.Its destructive force aside, the bomb represented the pinnacle of American scientific development in the mid-20th century. And even as scientists like J. Robert Oppenheimer seemed rather horrified at what they'd unleashed, others became more consumed by the scientific possibilities of the atomic age. The most famous proponent of nuclear was Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb and one of the inspirations for Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove. As the world's superpowers raced towards mutually-assured destruction, Teller became more enthusiastic about finding potential non-weapon uses for the phenomenal power of splitting or fusing the atom. Teller liked nuclear energy; his final paper, in 2006, would detail how to build an underground thorium reactor. But as the Cold War heated up, Teller became obsessed with using actual atomic bombs for civil engineering. Thanks to that type of numbers-driven thinking — if a bomb is as powerful as a million tons of TNT, why not use it to reshape the Panama Canal? — as well as Teller's incessant prodding, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) created Project Chariot. The mission: to create a new port in northwestern Alaska using a series of underwater nuclear explosions.Project Chariot was born in 1958 out of the AEC's cartoonishly-named Operation Plowshare, whose mission, begun in 1957 at the University of California Radiation Laboratory in Livermore, was to find peacetime uses for atomic bombs. I say cartoonish because Teller, who was a driving force behind the project, actually did propose the use of a couple dozen A-bombs as a giant shovel to widen the Panama Canal, amongst other similarly giant projects. But the Plowshare name has been attributed to Isaiah 2:3-5, a passage focused on repurposing the weapons of war for the tools of peace:They will beat their swords into plowshares

As the world's superpowers raced towards mutually-assured destruction, Teller became more enthusiastic about finding potential non-weapon uses for the phenomenal power of splitting or fusing the atom. Teller liked nuclear energy; his final paper, in 2006, would detail how to build an underground thorium reactor. But as the Cold War heated up, Teller became obsessed with using actual atomic bombs for civil engineering. Thanks to that type of numbers-driven thinking — if a bomb is as powerful as a million tons of TNT, why not use it to reshape the Panama Canal? — as well as Teller's incessant prodding, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) created Project Chariot. The mission: to create a new port in northwestern Alaska using a series of underwater nuclear explosions.Project Chariot was born in 1958 out of the AEC's cartoonishly-named Operation Plowshare, whose mission, begun in 1957 at the University of California Radiation Laboratory in Livermore, was to find peacetime uses for atomic bombs. I say cartoonish because Teller, who was a driving force behind the project, actually did propose the use of a couple dozen A-bombs as a giant shovel to widen the Panama Canal, amongst other similarly giant projects. But the Plowshare name has been attributed to Isaiah 2:3-5, a passage focused on repurposing the weapons of war for the tools of peace:They will beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks.

Nation will not take up sword against nation,

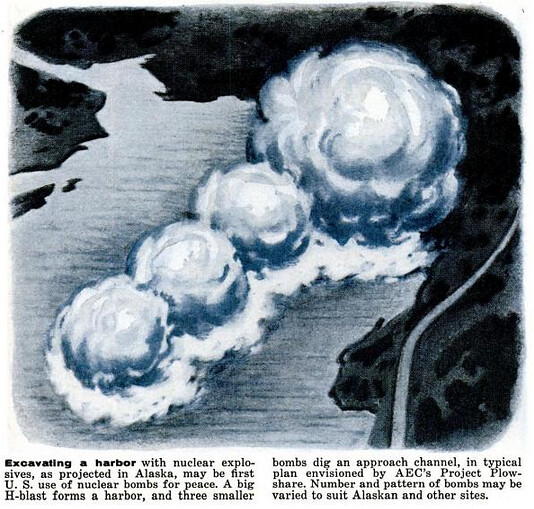

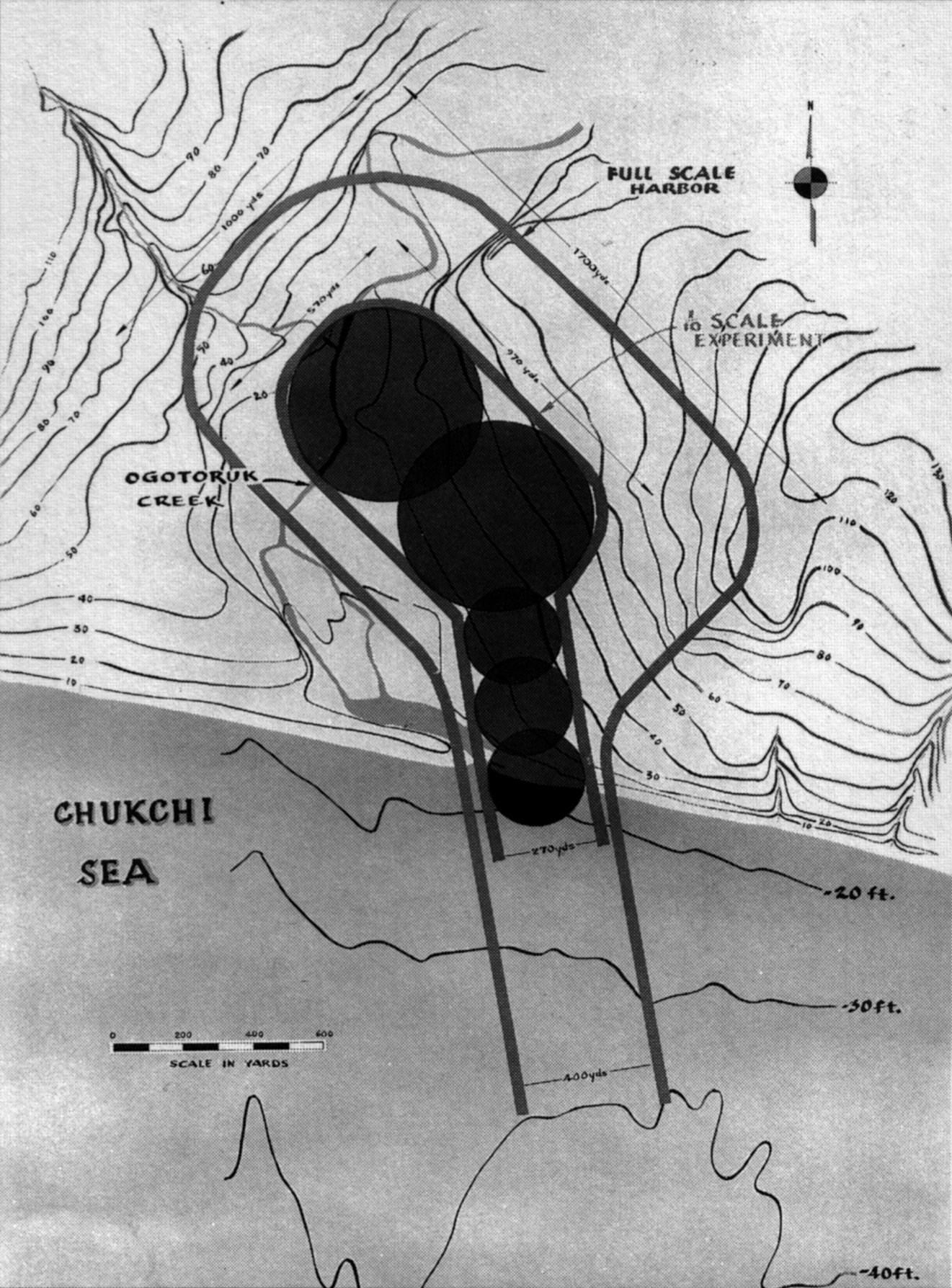

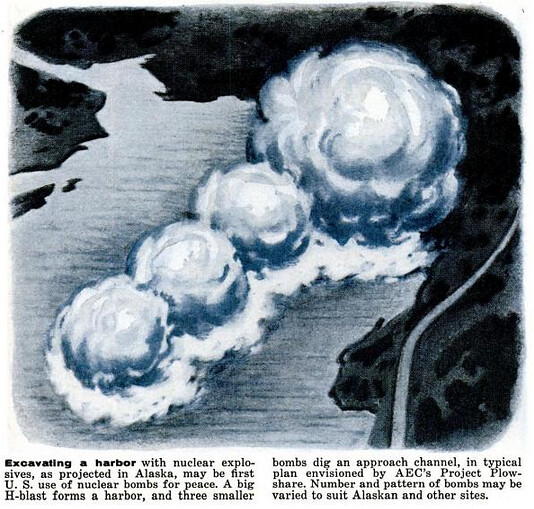

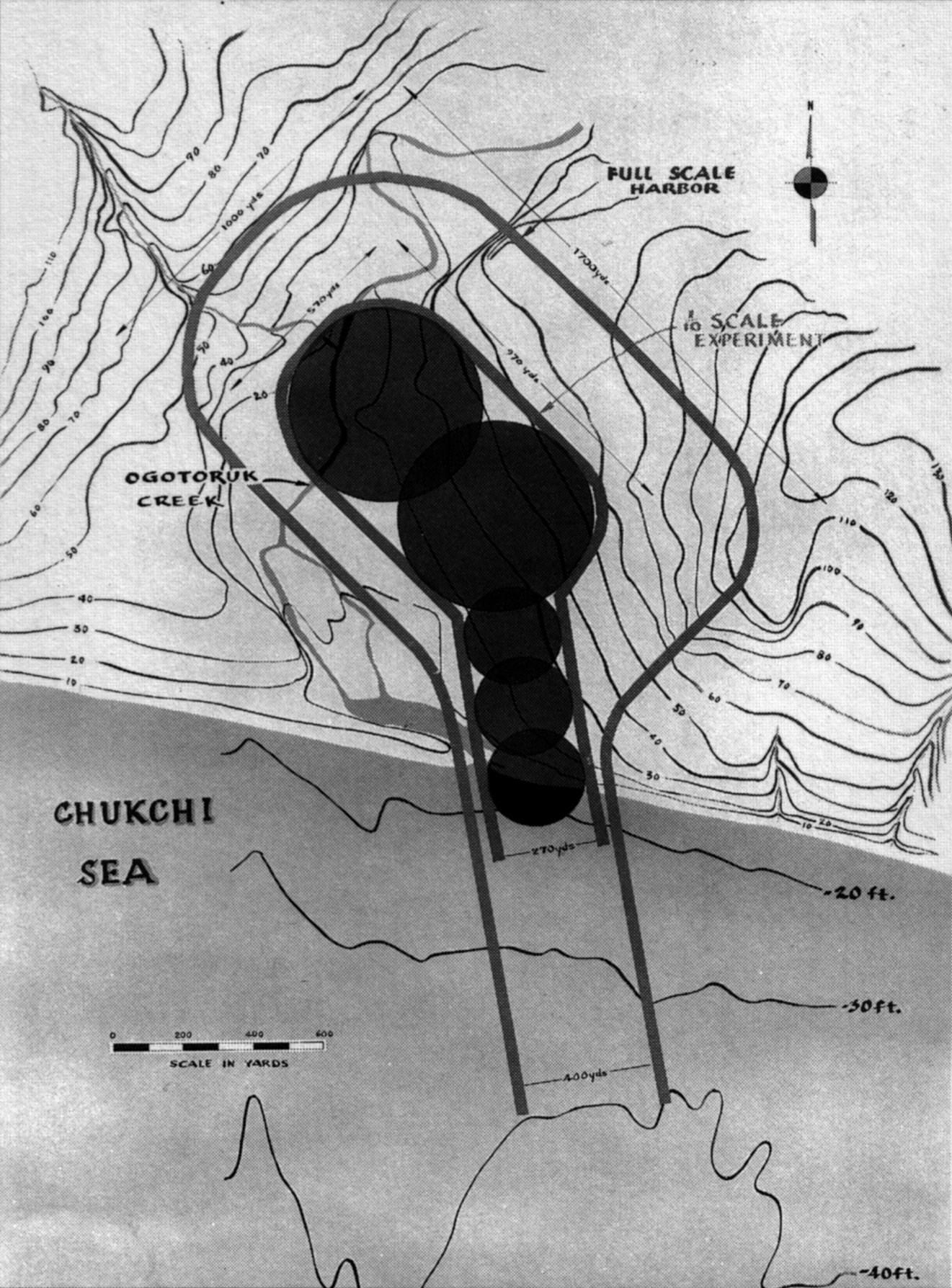

nor will they train for war anymore.To say that Plowshare was massive in scope would be a comical understatement."In considering possible tasks, the imagination is free to explore projects hundreds or thousands of times larger than have ever been undertaken," Dr. Gerald Johnson, who was co-director of Plowshare with Dr. Harold Brown, told Popular Science in 1958. The implication was simple: Now that mankind could blow things up orders of magnitude more efficiently than it could before, what piddling public works project could stand it its way?Plowshare's vision was as enormous as its tools. One proposal, called Project Carryall, would have used nuclear bombs to cut a new 11,000 foot long railway pass through the Bristol Mountains in California. According to a 1964 feasibility study, Carryall would have required 22 bombs ranging between 20 and 200 kilotons to make the deepest parts of the pass, which would have measured about 350 feet deep. Parts of the pass ranging around 100 feet deep would have been dug with conventional means for "technological and economic reasons."Another Plowshare project, Project Gnome, was even more ambitious. While it was partly meant to be a study of how underground nuclear explosions interacted with the rock around them, it was also an attempt to sort out how electrical energy could be produced from underground detonations (pdf). Gnome was first announced in 1958 during a U.S.-Soviet moratorium on nuclear testing. But after the Soviets broke the self-imposed ban in late 1961 with the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful weapon in history, the U.S. went ahead with Gnome, burying a 3.1 kiloton device over 1,100 feet deep in a massive salt deposit below New Mexico in what was the first "peaceful nuclear explosion" (PNE) carried out by the Plowshare program.According to a Defense Nuclear Agency report concerned with health problems in soldiers exposed to radiation, Gnome was tasked with studying "the possibility of converting the heat produced by a nuclear explosion into steam for the production of electric power," which would be caused by the immense heat of a massive molten salt slurry, as well as exploring "the feasibility of recovering radioisotopes for scientific and industrial applications." In essence, Gnome was an attempt at trapping a nuclear explosion underground in order to either siphon off the heat it created (in the form of steam or molten salt) to produce power, or recover expensive and hard to produce isotopes trapped within. The only problem, as the DNA report notes, was it wasn't exactly easy to seal off a nuclear explosion buried in fragile rock:Although it had been planned as a contained explosion, GNOME vented to the atmosphere. A cloud of steam started to appear at the top of the shaft two to three minutes after the detonation. Gray smoke and steam, with associated radioactivity, emanated from the shaft opening about seven minutes after the detonation. Radioactive materials vented to the atmosphere about 340 meters southwest of ground zero. Still, despite Gnome's release of radioactive steam just 25 miles southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico, the door had been opened for so-called peaceful nuclear explosions. Project Sedan, whose crater is shown above, was the second Plowshare experiment to be carried out. It basically was a test to see how big of a hole a nuclear bomb could make. It proved to be a really big hole. The 104-kiloton device moved 12 million tons of earth, producing the largest man-made crater in the country, which measured 1,280 feet wide and 320 feet deep. Shot in Nevada, Sedan spewed fallout over Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, and South Dakota, and contaminated more Americans than any other nuclear test.Plowshare went on to feature a total of 27 blasts, mostly at the Department of Energy's Nevada Test Site. But the final Plowshare test, which was likely the most audacious one to be carried out, was fired in May 1973 at Rifle, Colorado. Project Rio Blanco was an attempt to release 300 trillion cubic feet of natural gas under the Rocky Mountains by blasting apart caverns more than a mile deep with a trio of 33-kiloton bombs. It was the final of three attempts by Plowshare researchers to create what basically amounted to nuclear fracking, and, as noted by a 1973 Time article, came at a time when Plowshare was under increasing attack by, well, nearly everyone. The test didn't work, and thanks to nuclear contamination and damage from gas flares, the Rio Blanco test area is still a huge mess.Needless to say, Project Plowshare created environmental disasters everywhere it traveled during its 12 year run of active testing. What's rather absurd, however, is that despite a rather terrible track record — both environmentally as well as in terms of meeting stated goals — Plowshare wasn't shuttered until 1977, two decades after it was conceived, amidst public uproar."Project Gnome vented radioactive steam over the very press gallery that was called to confirm its safety," writes Benjamin Sovacool in his book Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power. "The next blast, a 104-kiloton detonation at Yucca Flat, Nevada, displaced 12 million tons of soil and resulted in a radioactive dust cloud that rose 12,000 feet and plumed toward the Mississippi River. Other consequences – blighted land, relocated communities, tritium-contaminated water, radioactivity, and fallout from debris being hurled high into the atmosphere – were ignored and downplayed until the program was terminated in 1977, due in large part to public opposition."But Plowshare's skeptics didn't simply emerge in the months before Rio Blanco, or even Gnome. Plowshare had been a source of controversy since long before the dissolution of the nuclear testing moratorium made its numerous live tests possible.Plowshare was first conceived by the AEC as a chance to rehabilitate the image of nuclear explosives following years of above-ground weapons testing by both the U.S. and Soviet Russia. It was born out of the belief among AEC scientists that nuclear power could indeed be harnessed for constructive purposes. And yet, even when the project was formally inaugurated, in June 19, 1957, scientists had no clear initial applications in mind.That changed with the launch of Sputnik by the USSR in October 1957. In what stands as the preeminent example of the high-stakes one-upmanship that fueled the Cold War, Sputnik's launch put a ton of pressure on U.S. researchers to come up with a similar marquee scientific achievement. As historian Norman Chance explains, scientists at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory suggested that using nuclear bombs as huge shovels would offer the "highest probability of early beneficial success" in the early stages of Plowshare. On a tight time frame, it was a lot easier to simply blast a giant hole in the ground than to build a massive underground water-filled chamber that could contain continual steam-generating nuclear blasts — which indeed was another early proposal.Teller, of course, supported the nuclear shovel idea wholeheartedly, and suggested Cape Thompson, in the Ogotoruk Valley way up in Northwest Alaska, as the perfect location for a test. In light of the Plowshare programs that would eventually be carried out, Teller's early proposal was absolutely over the top: a 2.4 megaton device would be buried off the coast and detonated to instantly create a new deep-water harbor that could be used to tap into northern Alaska's rich coal, oil, and mineral resources. That proposal became known as Project Chariot.Just 30 miles away from the proposed Chariot site sits Point Hope, an Inuit fishing town whose population numbered around 300 in the late 50s. Alaska, which didn't become a state until January 1959, was still considered to be little more than a barren territory thousands of miles away from Washington. So when Chariot was first proposed, along with the AEC's request for a test area larger than Rhode Island, the fact that Cape Thompson was mere miles from an Inuit town that had hosted residents for nearly 2,200 years did not register much concern. In 1959, the AEC received approval from the Bureau of Land Management to reserve 1,024,000 acres for testing, and the AEC soon began building facilities to house up to 90 working researchers.Surprisingly, according to a report by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a number of Alaskans were all for the AEC's work in the territory. In 1960, George Sundberg, the editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, wrote "We think the holding of a huge nuclear blast in Alaska would be a fitting overture to the new era which is opening for our state." For a budding Alaska looking to secure federal investment and its statehood, a project like Chariot seemed like the perfect chance to open its doors to power players in American science.Notice the awe with which he regards the potential of civil nuclear explosives, which, in his defense, was hardly limited to himself. How were otherwise intelligent people able to so easily look past the incredible dangers of fallout? Like the Plowshare director in that 1958 Popular Science article, some researchers were still pushing the idea that a "clean" bomb – as in, one with little to no fallout – was technically possible. This is how the magazine discusses the idea, somehow with a straight face:Using the cleanest available type of bomb would be desirable to reduce the usually heavy fallout of surface or near-surface blasts. The major part of any fallout will descend, downwind, within 200 miles of the site.'Hottest' after the detonation, radioactively, will be the harbor-forming crater itself. (Even a 100-percent-clean bomb would induce a little radioactivity, for a time, in nearby earth or rock.) But the crater will be immediately inundated, and partly submerged, by the sea. Tides, washing in and out, will speed the gradual dying-down of the radioactivity by carrying some away. Within several months at most, it should be safe to enter and use the harbor.In short, the proposed blast would flood the ocean with some radioactivity and launch a radioactive cloud that would spread only 200 miles. Teller, speaking in Fairbanks, sold Alaskans on Chariot by saying that nuclear explosions were so easily controlled that the Chariot team could "dig a harbor in the shape of a polar bear, if desired." And as insane as that sounds, note that Chariot came two decades before Three Mile Island. The true danger of radiation was only just becoming known to the general public.

Still, despite Gnome's release of radioactive steam just 25 miles southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico, the door had been opened for so-called peaceful nuclear explosions. Project Sedan, whose crater is shown above, was the second Plowshare experiment to be carried out. It basically was a test to see how big of a hole a nuclear bomb could make. It proved to be a really big hole. The 104-kiloton device moved 12 million tons of earth, producing the largest man-made crater in the country, which measured 1,280 feet wide and 320 feet deep. Shot in Nevada, Sedan spewed fallout over Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, and South Dakota, and contaminated more Americans than any other nuclear test.Plowshare went on to feature a total of 27 blasts, mostly at the Department of Energy's Nevada Test Site. But the final Plowshare test, which was likely the most audacious one to be carried out, was fired in May 1973 at Rifle, Colorado. Project Rio Blanco was an attempt to release 300 trillion cubic feet of natural gas under the Rocky Mountains by blasting apart caverns more than a mile deep with a trio of 33-kiloton bombs. It was the final of three attempts by Plowshare researchers to create what basically amounted to nuclear fracking, and, as noted by a 1973 Time article, came at a time when Plowshare was under increasing attack by, well, nearly everyone. The test didn't work, and thanks to nuclear contamination and damage from gas flares, the Rio Blanco test area is still a huge mess.Needless to say, Project Plowshare created environmental disasters everywhere it traveled during its 12 year run of active testing. What's rather absurd, however, is that despite a rather terrible track record — both environmentally as well as in terms of meeting stated goals — Plowshare wasn't shuttered until 1977, two decades after it was conceived, amidst public uproar."Project Gnome vented radioactive steam over the very press gallery that was called to confirm its safety," writes Benjamin Sovacool in his book Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power. "The next blast, a 104-kiloton detonation at Yucca Flat, Nevada, displaced 12 million tons of soil and resulted in a radioactive dust cloud that rose 12,000 feet and plumed toward the Mississippi River. Other consequences – blighted land, relocated communities, tritium-contaminated water, radioactivity, and fallout from debris being hurled high into the atmosphere – were ignored and downplayed until the program was terminated in 1977, due in large part to public opposition."But Plowshare's skeptics didn't simply emerge in the months before Rio Blanco, or even Gnome. Plowshare had been a source of controversy since long before the dissolution of the nuclear testing moratorium made its numerous live tests possible.Plowshare was first conceived by the AEC as a chance to rehabilitate the image of nuclear explosives following years of above-ground weapons testing by both the U.S. and Soviet Russia. It was born out of the belief among AEC scientists that nuclear power could indeed be harnessed for constructive purposes. And yet, even when the project was formally inaugurated, in June 19, 1957, scientists had no clear initial applications in mind.That changed with the launch of Sputnik by the USSR in October 1957. In what stands as the preeminent example of the high-stakes one-upmanship that fueled the Cold War, Sputnik's launch put a ton of pressure on U.S. researchers to come up with a similar marquee scientific achievement. As historian Norman Chance explains, scientists at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory suggested that using nuclear bombs as huge shovels would offer the "highest probability of early beneficial success" in the early stages of Plowshare. On a tight time frame, it was a lot easier to simply blast a giant hole in the ground than to build a massive underground water-filled chamber that could contain continual steam-generating nuclear blasts — which indeed was another early proposal.Teller, of course, supported the nuclear shovel idea wholeheartedly, and suggested Cape Thompson, in the Ogotoruk Valley way up in Northwest Alaska, as the perfect location for a test. In light of the Plowshare programs that would eventually be carried out, Teller's early proposal was absolutely over the top: a 2.4 megaton device would be buried off the coast and detonated to instantly create a new deep-water harbor that could be used to tap into northern Alaska's rich coal, oil, and mineral resources. That proposal became known as Project Chariot.Just 30 miles away from the proposed Chariot site sits Point Hope, an Inuit fishing town whose population numbered around 300 in the late 50s. Alaska, which didn't become a state until January 1959, was still considered to be little more than a barren territory thousands of miles away from Washington. So when Chariot was first proposed, along with the AEC's request for a test area larger than Rhode Island, the fact that Cape Thompson was mere miles from an Inuit town that had hosted residents for nearly 2,200 years did not register much concern. In 1959, the AEC received approval from the Bureau of Land Management to reserve 1,024,000 acres for testing, and the AEC soon began building facilities to house up to 90 working researchers.Surprisingly, according to a report by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a number of Alaskans were all for the AEC's work in the territory. In 1960, George Sundberg, the editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, wrote "We think the holding of a huge nuclear blast in Alaska would be a fitting overture to the new era which is opening for our state." For a budding Alaska looking to secure federal investment and its statehood, a project like Chariot seemed like the perfect chance to open its doors to power players in American science.Notice the awe with which he regards the potential of civil nuclear explosives, which, in his defense, was hardly limited to himself. How were otherwise intelligent people able to so easily look past the incredible dangers of fallout? Like the Plowshare director in that 1958 Popular Science article, some researchers were still pushing the idea that a "clean" bomb – as in, one with little to no fallout – was technically possible. This is how the magazine discusses the idea, somehow with a straight face:Using the cleanest available type of bomb would be desirable to reduce the usually heavy fallout of surface or near-surface blasts. The major part of any fallout will descend, downwind, within 200 miles of the site.'Hottest' after the detonation, radioactively, will be the harbor-forming crater itself. (Even a 100-percent-clean bomb would induce a little radioactivity, for a time, in nearby earth or rock.) But the crater will be immediately inundated, and partly submerged, by the sea. Tides, washing in and out, will speed the gradual dying-down of the radioactivity by carrying some away. Within several months at most, it should be safe to enter and use the harbor.In short, the proposed blast would flood the ocean with some radioactivity and launch a radioactive cloud that would spread only 200 miles. Teller, speaking in Fairbanks, sold Alaskans on Chariot by saying that nuclear explosions were so easily controlled that the Chariot team could "dig a harbor in the shape of a polar bear, if desired." And as insane as that sounds, note that Chariot came two decades before Three Mile Island. The true danger of radiation was only just becoming known to the general public. But that's not to say that the facts about radiation weren't known at all. It was simply that the American people, it was determined, couldn't handle them. Peter Libassi, the chairman of the Interagency Task Force on the Health Effects of Ionizing Radiation, explained that "[There was] a general atmosphere and attitude that the American people could not be trusted with the uncertainities, and therefore the information was withheld from them. I think there was concern that the American people, given the facts, would not make the right risk-benefit judgments." Citizens at Point Hope — like civilians and soldiers throughout the Cold War era — weren't educated fully in the dangers, because it could mean a roadblock to the development of "peaceful" nuclear power.So while it was clear that detonating a 2.4 megaton device just 30 miles from Point Hope (and, as later plans suggested, perhaps three more bombs to create a channel into the harbor) would likely blanket the community in fallout, the AEC told Point Hope residents that everything would be just fine. It wasn't until 1960, a full two years after Chariot was conceived and Teller had begun building support around the state, that AEC officials first paid a visit to Point Hope.A young geographer named Don Charles Foote, who was attached to the Environmental Studies Program of the AEC, wrote a follow-up report to the officials' visit that shows the AEC was feeding the town a pack of lies:To the detriment of the Commission and Project Chariot, the officials who spoke in March, 1960, made several statements which could not be substantiated in fact. Among other things the Point Hope people were told that the fish in and around the Pacific Proving Grounds were not made radioactive by nuclear weapons tests and [there would not be]… any danger to anyone if the fish were utilized; that the effects of nuclear weapons testing never injured any people, anywhere; that once the severely exposed Japanese people recovered from radiation sickness…there were no side effects; that the residents of Point Hope would not feel any seismic shock at all from Project Chariot; and that copies of the Environmental Program studies would be made immediately available to the Point Hope council upon the return of the AEC officials to California.

But that's not to say that the facts about radiation weren't known at all. It was simply that the American people, it was determined, couldn't handle them. Peter Libassi, the chairman of the Interagency Task Force on the Health Effects of Ionizing Radiation, explained that "[There was] a general atmosphere and attitude that the American people could not be trusted with the uncertainities, and therefore the information was withheld from them. I think there was concern that the American people, given the facts, would not make the right risk-benefit judgments." Citizens at Point Hope — like civilians and soldiers throughout the Cold War era — weren't educated fully in the dangers, because it could mean a roadblock to the development of "peaceful" nuclear power.So while it was clear that detonating a 2.4 megaton device just 30 miles from Point Hope (and, as later plans suggested, perhaps three more bombs to create a channel into the harbor) would likely blanket the community in fallout, the AEC told Point Hope residents that everything would be just fine. It wasn't until 1960, a full two years after Chariot was conceived and Teller had begun building support around the state, that AEC officials first paid a visit to Point Hope.A young geographer named Don Charles Foote, who was attached to the Environmental Studies Program of the AEC, wrote a follow-up report to the officials' visit that shows the AEC was feeding the town a pack of lies:To the detriment of the Commission and Project Chariot, the officials who spoke in March, 1960, made several statements which could not be substantiated in fact. Among other things the Point Hope people were told that the fish in and around the Pacific Proving Grounds were not made radioactive by nuclear weapons tests and [there would not be]… any danger to anyone if the fish were utilized; that the effects of nuclear weapons testing never injured any people, anywhere; that once the severely exposed Japanese people recovered from radiation sickness…there were no side effects; that the residents of Point Hope would not feel any seismic shock at all from Project Chariot; and that copies of the Environmental Program studies would be made immediately available to the Point Hope council upon the return of the AEC officials to California. It's interesting that the officials took such a definitive stance that Chariot wouldn't cause environmental damage when the predicted results of the explosion were nothing more than guesses. It was unclear if the Alaskan tundra would react in the same way to an underground blast as test sites in Nevada and the Pacific, and as an excellent Harper's article from 1962 points out, the AEC's prediction that only five percent of the bomb's radioactive yield would have ended up as fallout could have also been one percent or 25 percent, according to other experts versed in available data. How dirty such an explosion would be was simply unknown, despite the AEC's assertion.Perhaps because the AEC was so adamant that there would be zero environmental damages, Point Hope residents were immediately skeptical of Chariot. In 1961, as the project seemed to be gaining steam, the Point Hope Village Council wrote a scathing letter to President Kennedy stating that Chariot was too close to the town and the fishing grounds the town subsisted on. From a section of the letter quoted in Harper's:We read about "the cumulative and retained isotope burden in man that must be considered." We also know about strontium 90, how it might harm people if too much of it get in our body. We have seen the Summary Reports of 1960, National Academy of Sciences on "The Biological Effects of Atomic Radiation." We are deeply concerned about the health of our people now and for the future that is coming.In fact, the Inuit were being contaminated by bomb radiation well before any test had come anywhere near their homes. The report the Point Hope council refers to, amongst a wealth of other work, showed that Eskimos who subsisted on hunting caribou in the vast regions encompassed by Project Chariot had already showed high levels of harmful radionuclides in their bodies. By some reports, their results seemed to "to be higher in Sr 90 (Strontium 90) content than any other group in the world."The blame lay with worldwide nuclear testing, decades of which caused tons of radioactive dust to be launched into the atmosphere. That radioactive dust was eventually absorbed in vast quantities by the lichen (which survive in harsh conditions by absorbing airborne minerals) that cover the Alaskan tundra. Caribou fed on the lichen, and the Inuit fed on the caribou, which meant the citizens of Point Hope were being poisoned by nuclear testing even before Chariot had been proposed.Because of those studies, some scientists joined Point Hope residents and a small subset of conservationists in opposing the project. A pair of scientists working at the AEC station in Cape Thompson were relieved of their duties, while others were allegedly blacklisted from working elsewhere. But eventually, mounting pressure from those groups, as well as excellent reportage like that from Paul Brooks and Joseph Foote at Harper's, changed the political calculus. Chariot became too costly a project because of the growing uproar, especially when sites in Nevada were more than feasible test sites. Chariot, or at least the explosion part, was shelved.Although the AEC decided not to detonate thermonuclear bombs at Cape Thompson, the agency still had a million acres of free land to play with. So it decided to try to solve a riddle it had previously posed to the U.S. Geological Survey: Would underground nuclear explosions poison drinking water? The AEC, in all its brilliance, conducted its tests by throwing imported radioactive material on the ground, watering it to simulate rainfall, and testing the runoff.Archival footage of Point Hope residents from 1941. Via Alaska's Digital ArchiveI'll bet you can guess the outcome of that. An investigation in the early '90s, found that the residents of Point Hope had suffered from extremely high rates of cancer in the previous 30 years thanks to radioactive material poisoning their food and water supply."We, the Inupiat of Point Hope, have the ability to face the arrogant policies of the former Atomic Energy Commission and its Project Chariot," read an October 1992 press release from the village. "We will not be willing victims for the genocidal and inhuman policies of the Nuclear Energy Commission." But while the Point Hope residents were indeed vocal and unwilling victims, that didn't stop the AEC from conducting its "peaceful" work. Forty years later, the residents of Point Hope are still making noise because their traditions are being threatened by — you guessed it — climate change."Today we do not covet the boundless expanse of tundra where the caribou range at will, as did once the buffalo on the great plains," Brooks and Foote of Harper's wrote in their excellent summation of Point Hope. "The Alaskan Eskimos offer no threat to our way of life; how far must we inevitably be a threat to theirs?"Their report was published before Chariot was officially canceled, but I doubt their refrain would have changed. Chariot stands as a testament to the cold calculus that fueled all facets of the Cold War nuclear age, even when nuclear scientists were shooting for peaceful uses for bombs. While Oppenheimer and Einstein struggled with the reality of unleashing a power that's indescribable in its might, Teller and the folks at the AEC were blinded, shunning all human considerations in pursuit of an attempt at taming that power.It's possible to try to understand the giddy excitement of riding the cutting edge of physics and technology; just glancing at the buoyant prose in Popular Science at the time shows just how infectious the massive possibilites swirling around nonviolent megatons could be. And just imagine if one really could build a new railway through the mountains of California by unleashing a series of massive, clean bombs: the potential lives, money, and time saved by avoiding dangerous construction is incalculable. "If your mountain is not in the right place," Dr. Teller said in Anchorage, "just drop us a card." He was only partly kidding.But the reality never matched the dream. A decade or more of testing increasingly-massive bombs had poisoned the air and earth, and no matter how good the yields, any percentage of radioactive fallout released from bombs that large would be devastating to the local environment. It's a testament to the brutish single-mindedness of the AEC that it could tell such blatant lies in its supposed pursuit of utility. (There was no risk to Point Hope from 30 miles away? Give me a break.)Despite the cancellation of Project Chariot, there were still 27 live tests that were carried out by the AEC in its obsessive bid to keep playing with its toys. Plowshare stands as a shocking example of institutional addiction; one imagines a drunken artist saying he needs just one more glass to help him make his big breakthrough, even while lying facedown in a gutter oblivious to the filth around him. In the effort to make good on nuclear energy's promise, in the wake of its unrivaled destruction over Japan, the U.S. fiendishly tailored its facts to deceive the very people it was entrusted to protect.The end result, of course, were a series of endless half-truths and outright lies delivered to continue work that had long been proved to be far more costly than it was worth. The moral of that folly is equally clear: When offered the ability to chase after force with seemingly unlimited potential, there is no end to the lengths some will go to justify continuing that pursuit.Follow Derek Mead on Twitter: @derektmead.

It's interesting that the officials took such a definitive stance that Chariot wouldn't cause environmental damage when the predicted results of the explosion were nothing more than guesses. It was unclear if the Alaskan tundra would react in the same way to an underground blast as test sites in Nevada and the Pacific, and as an excellent Harper's article from 1962 points out, the AEC's prediction that only five percent of the bomb's radioactive yield would have ended up as fallout could have also been one percent or 25 percent, according to other experts versed in available data. How dirty such an explosion would be was simply unknown, despite the AEC's assertion.Perhaps because the AEC was so adamant that there would be zero environmental damages, Point Hope residents were immediately skeptical of Chariot. In 1961, as the project seemed to be gaining steam, the Point Hope Village Council wrote a scathing letter to President Kennedy stating that Chariot was too close to the town and the fishing grounds the town subsisted on. From a section of the letter quoted in Harper's:We read about "the cumulative and retained isotope burden in man that must be considered." We also know about strontium 90, how it might harm people if too much of it get in our body. We have seen the Summary Reports of 1960, National Academy of Sciences on "The Biological Effects of Atomic Radiation." We are deeply concerned about the health of our people now and for the future that is coming.In fact, the Inuit were being contaminated by bomb radiation well before any test had come anywhere near their homes. The report the Point Hope council refers to, amongst a wealth of other work, showed that Eskimos who subsisted on hunting caribou in the vast regions encompassed by Project Chariot had already showed high levels of harmful radionuclides in their bodies. By some reports, their results seemed to "to be higher in Sr 90 (Strontium 90) content than any other group in the world."The blame lay with worldwide nuclear testing, decades of which caused tons of radioactive dust to be launched into the atmosphere. That radioactive dust was eventually absorbed in vast quantities by the lichen (which survive in harsh conditions by absorbing airborne minerals) that cover the Alaskan tundra. Caribou fed on the lichen, and the Inuit fed on the caribou, which meant the citizens of Point Hope were being poisoned by nuclear testing even before Chariot had been proposed.Because of those studies, some scientists joined Point Hope residents and a small subset of conservationists in opposing the project. A pair of scientists working at the AEC station in Cape Thompson were relieved of their duties, while others were allegedly blacklisted from working elsewhere. But eventually, mounting pressure from those groups, as well as excellent reportage like that from Paul Brooks and Joseph Foote at Harper's, changed the political calculus. Chariot became too costly a project because of the growing uproar, especially when sites in Nevada were more than feasible test sites. Chariot, or at least the explosion part, was shelved.Although the AEC decided not to detonate thermonuclear bombs at Cape Thompson, the agency still had a million acres of free land to play with. So it decided to try to solve a riddle it had previously posed to the U.S. Geological Survey: Would underground nuclear explosions poison drinking water? The AEC, in all its brilliance, conducted its tests by throwing imported radioactive material on the ground, watering it to simulate rainfall, and testing the runoff.Archival footage of Point Hope residents from 1941. Via Alaska's Digital ArchiveI'll bet you can guess the outcome of that. An investigation in the early '90s, found that the residents of Point Hope had suffered from extremely high rates of cancer in the previous 30 years thanks to radioactive material poisoning their food and water supply."We, the Inupiat of Point Hope, have the ability to face the arrogant policies of the former Atomic Energy Commission and its Project Chariot," read an October 1992 press release from the village. "We will not be willing victims for the genocidal and inhuman policies of the Nuclear Energy Commission." But while the Point Hope residents were indeed vocal and unwilling victims, that didn't stop the AEC from conducting its "peaceful" work. Forty years later, the residents of Point Hope are still making noise because their traditions are being threatened by — you guessed it — climate change."Today we do not covet the boundless expanse of tundra where the caribou range at will, as did once the buffalo on the great plains," Brooks and Foote of Harper's wrote in their excellent summation of Point Hope. "The Alaskan Eskimos offer no threat to our way of life; how far must we inevitably be a threat to theirs?"Their report was published before Chariot was officially canceled, but I doubt their refrain would have changed. Chariot stands as a testament to the cold calculus that fueled all facets of the Cold War nuclear age, even when nuclear scientists were shooting for peaceful uses for bombs. While Oppenheimer and Einstein struggled with the reality of unleashing a power that's indescribable in its might, Teller and the folks at the AEC were blinded, shunning all human considerations in pursuit of an attempt at taming that power.It's possible to try to understand the giddy excitement of riding the cutting edge of physics and technology; just glancing at the buoyant prose in Popular Science at the time shows just how infectious the massive possibilites swirling around nonviolent megatons could be. And just imagine if one really could build a new railway through the mountains of California by unleashing a series of massive, clean bombs: the potential lives, money, and time saved by avoiding dangerous construction is incalculable. "If your mountain is not in the right place," Dr. Teller said in Anchorage, "just drop us a card." He was only partly kidding.But the reality never matched the dream. A decade or more of testing increasingly-massive bombs had poisoned the air and earth, and no matter how good the yields, any percentage of radioactive fallout released from bombs that large would be devastating to the local environment. It's a testament to the brutish single-mindedness of the AEC that it could tell such blatant lies in its supposed pursuit of utility. (There was no risk to Point Hope from 30 miles away? Give me a break.)Despite the cancellation of Project Chariot, there were still 27 live tests that were carried out by the AEC in its obsessive bid to keep playing with its toys. Plowshare stands as a shocking example of institutional addiction; one imagines a drunken artist saying he needs just one more glass to help him make his big breakthrough, even while lying facedown in a gutter oblivious to the filth around him. In the effort to make good on nuclear energy's promise, in the wake of its unrivaled destruction over Japan, the U.S. fiendishly tailored its facts to deceive the very people it was entrusted to protect.The end result, of course, were a series of endless half-truths and outright lies delivered to continue work that had long been proved to be far more costly than it was worth. The moral of that folly is equally clear: When offered the ability to chase after force with seemingly unlimited potential, there is no end to the lengths some will go to justify continuing that pursuit.Follow Derek Mead on Twitter: @derektmead.

Advertisement

A well-meaning weapon

and their spears into pruning hooks.

Nation will not take up sword against nation,

nor will they train for war anymore.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Chariot of really big fire

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement