One of the staples of the Christmas season is the display of nativity scenes, complete with baby Jesus, attendant livestock, and Myrrh-wielding Magi. Many nativity sets also include a representation of the Star of Bethlehem, which, in Christian tradition, guided the Magi to the manger where Jesus was cooling his heels, post-birth.

For centuries, the appearance of the star has been interpreted by theologians as a miraculous herald of Jesus Christ’s arrival on Earth. But a question remains: Was the Star of Bethlehem a mere literary flourish, or was there really a super-luminous object in sky around the time Jesus is thought to have been born?

Videos by VICE

One of the first people to investigate this question with any scientific rigor was the influential astronomer Johannes Kepler. After observing the increased luminosity resulting from a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 1604, he wound back the ephemeride clock, calculating that very rare conjunctions of Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars occurred in 7 and 6 BCE.

Hangin’ with Mr. Kepler. Image: Jean-Jacques MILAN

Weirdly enough, Kepler didn’t speculate that the conjoined light from the planets created the Star of Bethlehem effect, but rather that these planetary conjunctions somehow magically manifested an exploding star, using that to explain the legend.

Regardless of why he added that step, many other scientists have corroborated his research, though there is some doubt about how spectacular this unusual alignment of planets would have appeared. Others argue that the star may have been a result of an even more brilliant conjunction, this time between the Venus and Jupiter, which occurred in 2 BCE.

“Adoration of the Magi” by Giotto di Bondone, based on the artist’s observation of the comet. Image: Giotto di Bondone

There’s also a theory that the star may have been a comet, though these celestial visitors were typically interpreted as omens of death rather than harbingers of birth. The Romans recorded the 11 BCE appearance of Halley’s Comet, which may have been mistaken for a star, but other than that, there aren’t many good candidates that match the timeframe.

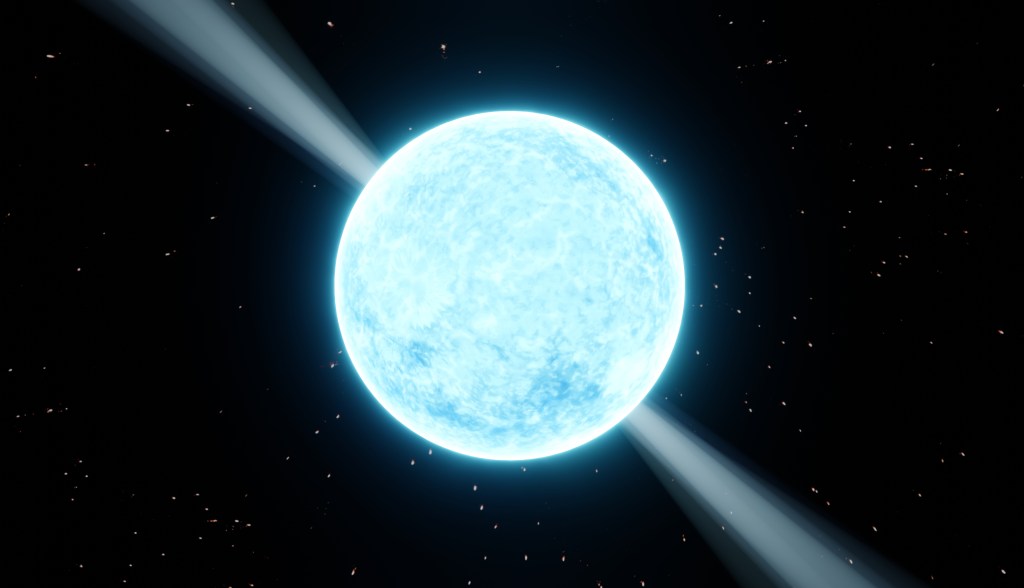

The most evocative explanation is that a supernova erupted into existence two millennia ago, captivating the world with its radiance. Arthur C. Clarke expanded this theory into a fantastic short story called “The Star,” which won a Hugo and was adapted into a Twilight Zone episode. It’s narrated by a spacefaring Jesuit priest who discovers the remains of a noble civilization in the ashes of a supernova.

“[T]here comes a point when even the deepest faith must falter,” says the priest at the story’s climax, “and now, as I look at the calculations lying before me, I have reached that point at last. […] Oh God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, that the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem?”

Clarke expertly milks this idea of a civilization-incinerating Supernova of Bethlehem for all its worth, and it’s definitely the most compelling explanation for the legendary brilliance of the object.

But though the theory can’t be ruled out, there’s very little evidence for it. Chinese skywatchers did note the appearance of a nova in the spring of 5 BCE, and that it was positioned above Jerusalem. But the event wasn’t recorded elsewhere, and wasn’t even considered to be a major event by the people who observed it.

Oh course, it’s entirely possible that the Star of Bethlehem is a complete fiction, or perhaps that it was co-opted from an earlier legend (like so much else of the Christ story). That’s as likely a theory as any, but I’m still partial to the notion that a real astronomical event inspired the story, even if it happened decades—or even centuries—before Jesus was thought to have lived.

Even the most cursory overview of human history emphasizes how much our species adores endowing astronomical events with supernatural meaning. This anthropomorphization of the skies is a universal keystone of our cultural evolution, and the trope of using celestial patterns to predict human affairs crops up frequently across eras and continents. Indeed, it still thrives today in comet conspiracy theories, Blood Moon prophecies, and the perplexing world of astrology.

As a non-Christian, I don’t have any real stake in the nativity’s riff on this deeply ingrained human storytelling technique. But as a human person, it is immensely satisfying to imagine an unusual planetary conjunction or a supernova inspiring one of the most widespread and long-lived narratives on the planet. Whatever the Star of Bethlehem was (or wasn’t), it is a reminder that legends presaged by exotic astronomical events are memorable as hell.