On Wednesday, National Geographic released a rare video glimpse of a Greenland shark, an elusive species that biologists know next to nothing about. The footage was captured by NatGeo mechanical engineer Alan Turchik, who operated an underwater dropcam in the waters surrounding Franz Josef Land, an uninhabited Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean.

Videos by VICE

The camera was deployed to a depth of 700 feet, and recorded three hours of footage of the frigid seafloor. To Turchik’s initial disappointment, the vista did not appear to be very promising. “There was literally no life,” he said in the video. “I thought the deployment was a bust. I was just kind of watching idly when all of a sudden, the camera shook.”

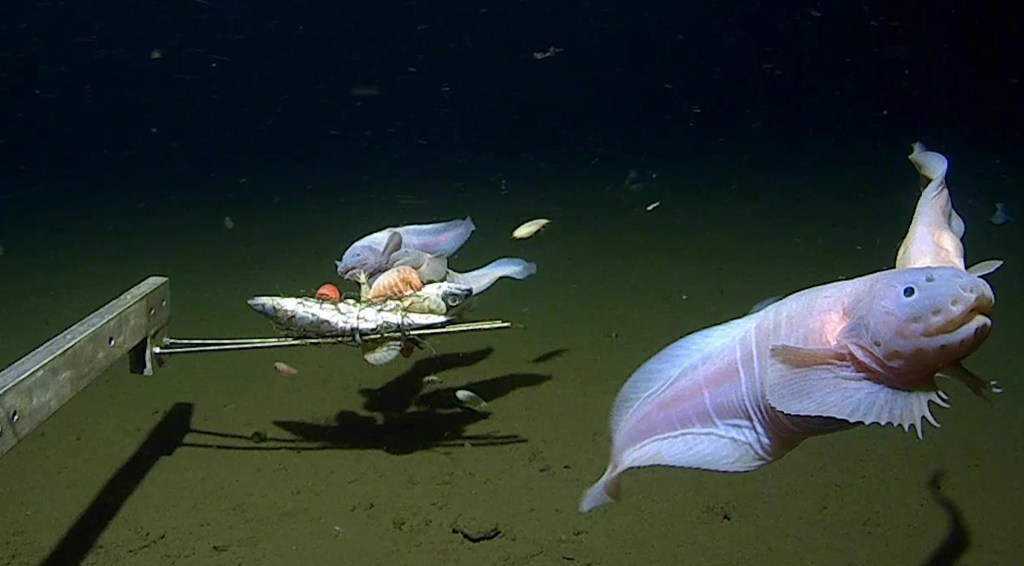

Enter: a Greenland shark, the first ever to be seen so far northeast. Turchik’s expletive-laden reaction to the animal’s grand entrance will strike a familiar chord with pretty much anyone involved with scientific research.

There is nothing more exciting than a new scientific discovery, but what’s often overlooked in the frenzy of such an event are the years—sometimes decades—of monotonous experimentation and meticulous revision leading up to it. The NatGeo video provides a neat little microcosm of the process redacted into two minutes.

Whether scientists are sampling the light of distant stars or investigating the peculiarities of the quantum universe, the general pattern seems to be “bored, bored, bored, HOLY SHIT.” So it was with this rare footage of a Greenland shark prowling the seafloor.

Along those lines, the video provides a welcome opportunity to gawk over one of the weirdest creatures in the ocean. At 6.5 feet long, this particular individual was small for a species that can produce hulking 23-foot long monsters.

But what it did have was the telltale languid pace of a Greenland shark. The animals are the slowest swimmers of all the sharks, traveling about 0.3 miles per hour on average. They are so leisurely that researchers have long questioned how exactly they manage to hunt and kill much nimbler prey like seal.

One current theory is that the sharks creepily sneak up on their prey while they are sleeping, but the jury is still out on that tactic. Like many basic details about the lives of Greenland sharks—like where they give birth, for example, or how long they live—their predatory behavior is shrouded in mystery.

One thing’s for certain though: The more biologists discover about these animals, the more bizarre they seem. Roughly 90 percent of the species are hosts to an eyeball-eating bacteria that renders them blind, and their flesh is so poisonous that when it was fed to sled dogs in a 1968 expedition, they suffered convulsions, explosive diarrhea, and death in some cases.

Some researchers have suggested that based on the shark’s slow growth rate, they may live to be over 200 years old. Also, they apparently scavenge anything. Polar bears, horses, moose, and, in one instance, a complete reindeer carcass, have been found inside the bellies of these beasts.

The video provided a welcome window into the world of this strange animal. But by making Turchik a subject of the film too, it also showcased a taste of the boom-and-bust cycle of scientific research, punctuated with a healthy dose of profanity.