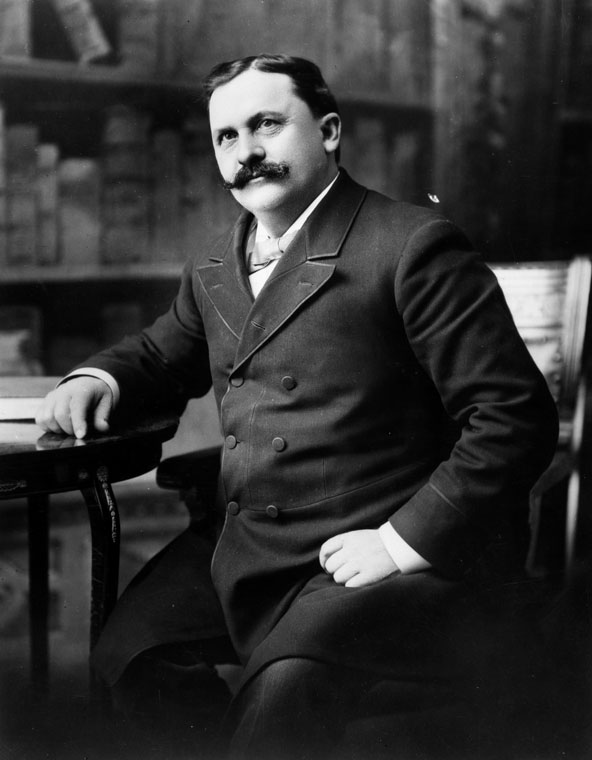

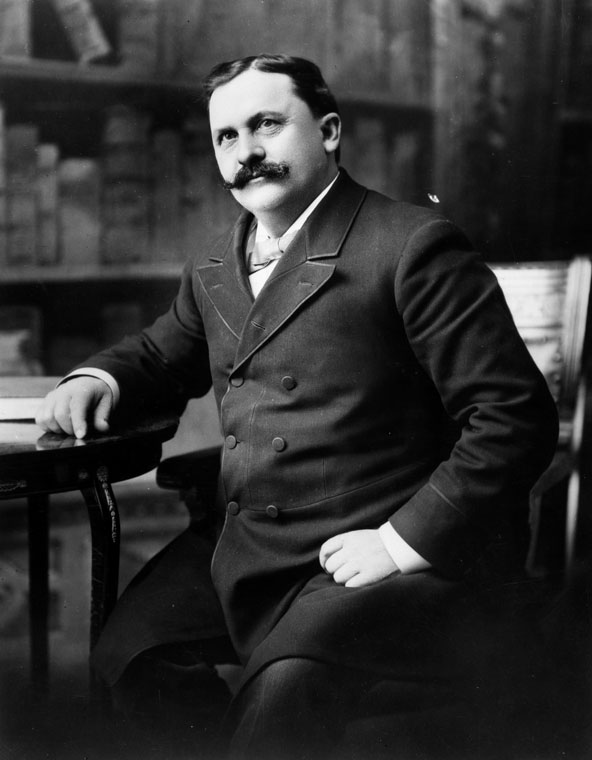

Depending on what you mean by "star gazing," Los Angeles is either the best or worst city in the country for the activity. Spend enough time cruising Sunset Blvd and you're bound to see at least one celebrity, but if we're talking constellations you'll be hard pressed to see a single star through the city's thick blanket of light pollution.Nevertheless, LA is home to a multi-million dollar observatory, and the story of its founder is almost as strange as hosting an observatory in a city without stars.Griffith Jenkins Griffith (no joke) was born in the UK on January 4, 1850 and lived with his grandparents until he immigrated to the United States at the age of 15. At the age of 23 he began managing a publishing company until the late 1870s when he became a mining correspondent for a newspaper in San Francisco. He gained extensive insight into the mining industry through his journalism and eventually put his expertise to work for various west coast mining syndicates which made him a millionaire.In 1882 Griffith moved to LA and purchased 4000 acres of land. In the mid-1890s he gifted the 3000 acres now known as Griffith Park to the city to be used as "a place of rest and relaxation for the masses." Griffith Griffith was married to his wife Christina in 1897, and the pair enjoyed their status as well-known and regarded LA socialites throughout the late '90s and into the early 20th century.But then in 1903, things took a turn for the utterly bizarre. On vacation with his wife of 16 years and their 15-year old son, Griffith had rented the presidential suite of the Arcadia Hotel in Santa Monica. According to a 1903 report by the Los Angeles Times, near the end of the vacation Griffith entered the hotel room with a revolver and told his wife that he was going to kill her."Get your prayer book and kneel down, and cover your eyes," Griffith told Christina, according to the Times. "I'm going to shoot you, and going to kill you."What the Times fails to mention in its coverage, however, is Griffith's reason for wanting to kill his wife: He was convinced she was conspiring with the Pope to poison him."Tina Griffith was from a prominent Los Angeles family that ran one of the top hotels in town and they happened to be Catholic," Michael Eberts, a professor of mass communication at Glendale Community College and proprietor of the Griffith Park History project, told Motherboard. "I think now we can't really wrap our heads around the early 20th century anti-catholicism, but Griffith had this weird religious baggage regarding his wife and when he drank he got paranoid."As you might imagine, trying to reason with an armed drunkard who was convinced his Catholic wife was working with the Pope to kill her Protestant husband wasn't really an option. Griffith pulled the trigger and the bullet struck Christina in the eye, blinding her. Miraculously she was able to leap from the balcony of the hotel and crawl to safety, despite suffering a fractured shoulder from the fall and having just been shot in the face.Although Griffith tried to claim that the shooting was accidental, he was tried in a high profile case for attempted murder. In an attempt to keep face in his high-society social circles, Griffith had kept his alcohol habit a secret from everyone but his immediate family for years. During the trial his alcoholism came to light and his charge was reduced to assault with a deadly weapon on the basis of "alcoholic insanity." It was one of the first time in the history of the US legal system that alcoholism was treated as a mental issue instead of simply a habit that was socially or morally reprehensible."After Griffith shot his wife he had this delusional idea that he was going to defend himself, but he quickly realized that that was a really bad idea," Eberts said. "So he went to Earl Rogers, the great defense attorney of that day and he was the one that came up with the alcoholic insanity defense. Rogers just threw himself into this case, perhaps in part because he himself was a terrible alcoholic."Despite Rogers' best efforts, Griffith ended up serving two years in San Quentin and sobering up. When he re-emerged onto the Los Angeles scene, Griffith was a disgraced man with a lot of money. In an attempt to rectify his wrongs, he offered the city $100,000 for the construction of an observatory on top of Mt. Hollywood in 1912 so that astronomy might be available to the public rather than restricted to scientists operating remote mountain laboratories."Griffith had gone to the observatory on Mt. Lowe in the San Gabriel mountains in the 1890s and apparently he looked through the telescope and remarked, 'If all of mankind could look through this it would revolutionize the world,'" said Eberts. "It was never meant to be a serious astronomical observatory. He wanted to have a place where the 'plain people' could come up the hill from their neighborhoods and contemplate things bigger than themselves."As per Griffith's offer, the observatory was to include an astronomical telescope available for public viewing, a "Hall of Science" to educate the public on the physical sciences and a movie theatre which would screen educational films.Obviously, the city was conflicted about accepting a donation from a guy who just got out of the clink for shooting his wife in the face and so the project stalled out for years. As he approached the end of his life, Griffith realized he would never see his vision come to fruition and outlined his plans for the observatory in his will.The Griffith Observatory was eventually constructed according to Griffith Griffith's specifications, but didn't open to the public until 1935, following input from leading astronomers about how it should be built. Today, the observatory adheres more or less to Griffith's original intentions, housing a telescope, Foucault's pendulum, a planetarium and a number of scientific exhibits that attract hundreds of thousands of tourists a year.In fact, one the few things you won't find at the observatory is a mention of these bizarre middle years of the institution's namesake.

On vacation with his wife of 16 years and their 15-year old son, Griffith had rented the presidential suite of the Arcadia Hotel in Santa Monica. According to a 1903 report by the Los Angeles Times, near the end of the vacation Griffith entered the hotel room with a revolver and told his wife that he was going to kill her."Get your prayer book and kneel down, and cover your eyes," Griffith told Christina, according to the Times. "I'm going to shoot you, and going to kill you."What the Times fails to mention in its coverage, however, is Griffith's reason for wanting to kill his wife: He was convinced she was conspiring with the Pope to poison him."Tina Griffith was from a prominent Los Angeles family that ran one of the top hotels in town and they happened to be Catholic," Michael Eberts, a professor of mass communication at Glendale Community College and proprietor of the Griffith Park History project, told Motherboard. "I think now we can't really wrap our heads around the early 20th century anti-catholicism, but Griffith had this weird religious baggage regarding his wife and when he drank he got paranoid."As you might imagine, trying to reason with an armed drunkard who was convinced his Catholic wife was working with the Pope to kill her Protestant husband wasn't really an option. Griffith pulled the trigger and the bullet struck Christina in the eye, blinding her. Miraculously she was able to leap from the balcony of the hotel and crawl to safety, despite suffering a fractured shoulder from the fall and having just been shot in the face.Although Griffith tried to claim that the shooting was accidental, he was tried in a high profile case for attempted murder. In an attempt to keep face in his high-society social circles, Griffith had kept his alcohol habit a secret from everyone but his immediate family for years. During the trial his alcoholism came to light and his charge was reduced to assault with a deadly weapon on the basis of "alcoholic insanity." It was one of the first time in the history of the US legal system that alcoholism was treated as a mental issue instead of simply a habit that was socially or morally reprehensible."After Griffith shot his wife he had this delusional idea that he was going to defend himself, but he quickly realized that that was a really bad idea," Eberts said. "So he went to Earl Rogers, the great defense attorney of that day and he was the one that came up with the alcoholic insanity defense. Rogers just threw himself into this case, perhaps in part because he himself was a terrible alcoholic."Despite Rogers' best efforts, Griffith ended up serving two years in San Quentin and sobering up. When he re-emerged onto the Los Angeles scene, Griffith was a disgraced man with a lot of money. In an attempt to rectify his wrongs, he offered the city $100,000 for the construction of an observatory on top of Mt. Hollywood in 1912 so that astronomy might be available to the public rather than restricted to scientists operating remote mountain laboratories."Griffith had gone to the observatory on Mt. Lowe in the San Gabriel mountains in the 1890s and apparently he looked through the telescope and remarked, 'If all of mankind could look through this it would revolutionize the world,'" said Eberts. "It was never meant to be a serious astronomical observatory. He wanted to have a place where the 'plain people' could come up the hill from their neighborhoods and contemplate things bigger than themselves."As per Griffith's offer, the observatory was to include an astronomical telescope available for public viewing, a "Hall of Science" to educate the public on the physical sciences and a movie theatre which would screen educational films.Obviously, the city was conflicted about accepting a donation from a guy who just got out of the clink for shooting his wife in the face and so the project stalled out for years. As he approached the end of his life, Griffith realized he would never see his vision come to fruition and outlined his plans for the observatory in his will.The Griffith Observatory was eventually constructed according to Griffith Griffith's specifications, but didn't open to the public until 1935, following input from leading astronomers about how it should be built. Today, the observatory adheres more or less to Griffith's original intentions, housing a telescope, Foucault's pendulum, a planetarium and a number of scientific exhibits that attract hundreds of thousands of tourists a year.In fact, one the few things you won't find at the observatory is a mention of these bizarre middle years of the institution's namesake.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement