In 2011, a team of marine ecologists led by Jon Copley sent a remotely operated submarine nearly two miles underwater to observe a field of hydrothermal vents in the southwest Indian Ocean. Copley and his team collected 21 animal specimens from the vents using the underwater vehicle and after years of taxonomical research were able to determine that six of these species had not yet been formally described.

As detailed in a paper published this week in Nature, the six new species include a hairy chested Hoff crab, two types of snails, one type of mollusk and two different species of worm.

Videos by VICE

A new species of scale worm discovered at the Longqi vent. Image: Copley, et al/ Southampton University

Hesiolyra Bergi, Another new species of worm discovered at Longqi. Image: Copley, et al/ Southampton University

Bathymodiolus marisindicus, a type of mollusk, discovered at Longqi. Image: Copley, et al/ Southampton University

Aside from their novelty, these species are remarkable for their ability to survive in the harsh ecosystem that a hydrothermal vent creates. These vents are the result of mineral-rich magma from deep inside the earth coming into contact with the near-freezing ocean water, forming chimney-like structures as the magma cools. These chimneys are rich in sulfide minerals, are used by microbes in a chemosynthetic process that leverages the oxygen in the seawater to oxidize the chemicals emerging from the vents for energy. These microbes form the basis of the vent ecosystem, providing food for the crabs, clams, snails and other species around the vent.

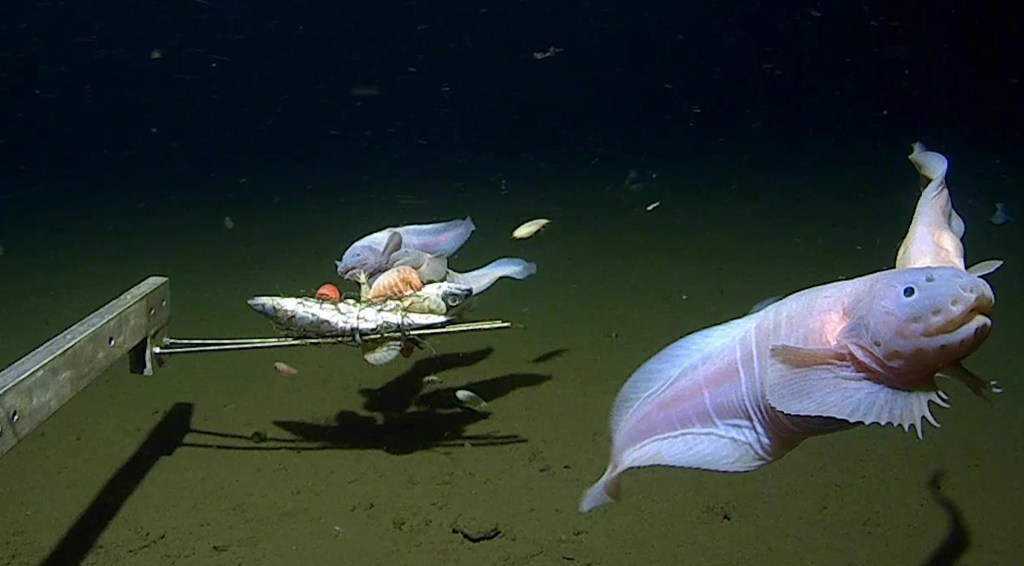

The vent field explored by Copley and his colleagues is known as Longqi, or Dragon’s Breath. It was first discovered in 1997, but it wasn’t until 2007 that an underwater drone captured the first images of the vents. Those photos revealed that these vents, some of which are over two stories tall, were also rich in copper and gold, making them especially attractive for deep-sea mining operations.

The Jabberwocky vent in the Longqi field. Image: Southampton University.

The Longqi vents cover an area of the ocean floor about the size of a football field that was licensed to the Chinese Ocean Minerals Research Agency (COMRA) by the United Nations International Seabed Authority in 2011. This license allows for some exploratory extraction of minerals from the seabed as well as the ability to test mining technology that will be used by COMRA after they have obtained an exploitation-phase license that allows for full-scale deep-sea mining operations.

According to Copley and his colleagues, their recent taxonomical survey of the Longqi vents is valuable not only for the newly discovered species, but also because it will provide a “baseline of ecological observations” so that scientists can have an idea of the degree to which deep-sea mining is harming animal life around the vents.

“Our results highlight the need to explore other hydrothermal vents in the southwest Indian Ocean and investigate the connectivity of their populations, before any impacts from mineral exploration activities and future deep-sea mining can be assessed,” Copley said.

Another interesting finding from the 2011 survey of the Longqi vents is that a number of the animal species found living on or around the vents had also been previously discovered at other hydrothermal vents thousands of miles away in the Antarctic and Eastern Pacific oceans.

“Finding these two species at Longqi shows that some vent animals may be more widely distributed across the oceans than we realized,” said Copley. “We can be certain that the new species we’ve found also live elsewhere in the southwest Indian Ocean, as they will have migrated here from other sites, but at the moment no-one really knows where, or how well-connected their populations are with those at Longqi.”

Unfortunately, depending on the rate at which the deep-sea mining industry develops and the degree to which it harms the poorly-understood ecosystems of the deep sea, Copley and his colleagues might never have a chance to find out.