Image: Derek Mead

The average American throws away over 1,130 pounds of garbage every year. Looking around my desk, I've got two disposable cups AND a can, a bag from lunch and its attendant garbage, and scraps of paper that I keep outlining and re-outlining this article on. I'm a slob; I'm reprehensible, a monster—and the world is just getting more like me.Peak garbage is still a century away. First, the amount of solid waste generated globally will practically double by the year 2025, up from 3.5 million tons per day to 6 million tons per day, before leveling off sometime after the year 2100 when, a World Bank projection indicates, we'll be producing 11 million tons of trash daily.That's where artist James Mercer's piece is set: 2157, post-garbage peak. “It seemed like a reasonable amount of time away,” he said when I asked why he chose that date. Standing amidst detritus both familiar and imagined, with the sounds of a class of amateur theremin players wailing up from downstairs, we agreed there was a natural poetry to the year.The artist in the landfill. Image: Derek Mead

Mercer's piece, “Landfill,” was set in the future, and now has moved to the past, having been up in the Clocktower residency space down at Pioneer Works in Red Hook until last Sunday.“Some of it was trash, and some of it will be again,” he told us the day before the exhibit closed, while Derek and I were swinging by the “Landfill." (Motherboard pro tip: if you're doing a future-oriented art project in Brooklyn, we're liable to show up the day before it closes, unless you email us twice.)As much as I feel wretchedly guilty for my personal tons o' trash, it's hard to make a case for why Mercer should save the squeezed out ketchup packets, or used earplugs (all his, he claimed), and anyway, enviro-guilt isn't really the point of “Landfill,” as much as that's the most glaringly obvious place for an exhibit about garbage to go.Image: Derek Mead

“I just sort of took garbage as a given. I started there,” Mercer said. “Futurology and scenario planning is a difficult thing to do, but one thing you can say with certainty is that we're going to leave a lot of shit behind.”So Mercer built stuff that doesn't yet exist as thrown away. “Landfill” combines the real-world trash of today that he collected, including a big bag of empty pill bottles found in Chinatown, with sculptures of imagined future trash that's made of found cardboard and paint, and a pretty disturbing video that we sat on (presumably discarded) half chairs and cushions to watch. Mercer hit play on a remote he kept hidden in one of the little dumpsters.Remote caddy/dumpster. Image: Derek Mead

The video—of paper ghosts that replicate themselves with scissors and lurk through a hellscape of people in branded t-shirts, who themselves fight and die of radiation poisoning—blended pretty seamlessly with the chaos of the room. Static cardboard flames stood in the corner. The world's worst branded name-brand stores (so Guitar Center) were reimagined as dilapidated castles.Rising above the fray. Image: Derek Mead

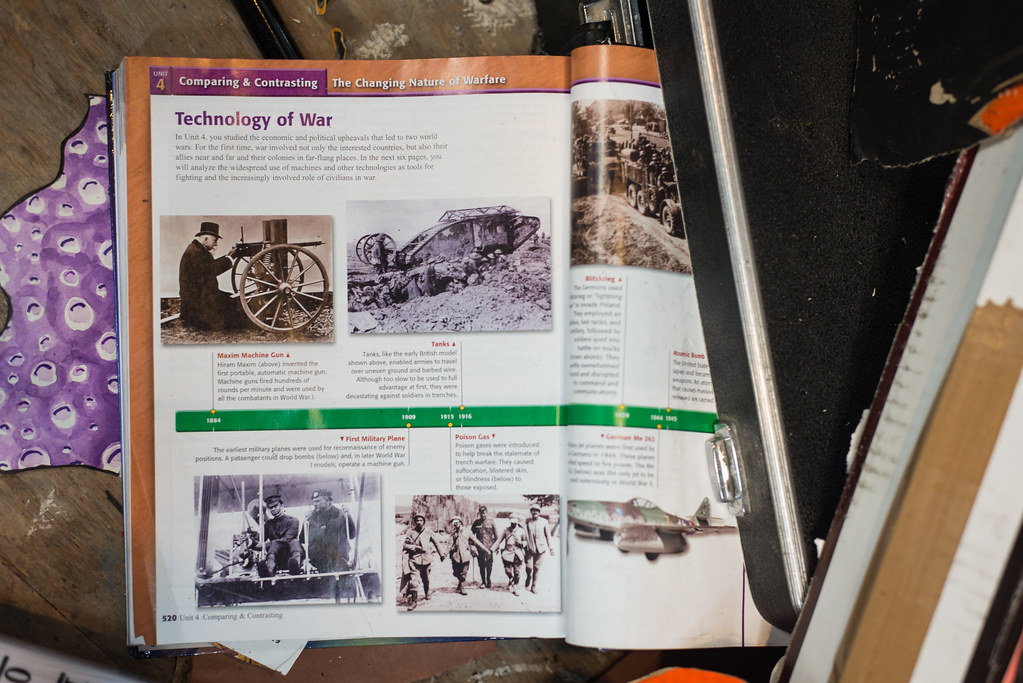

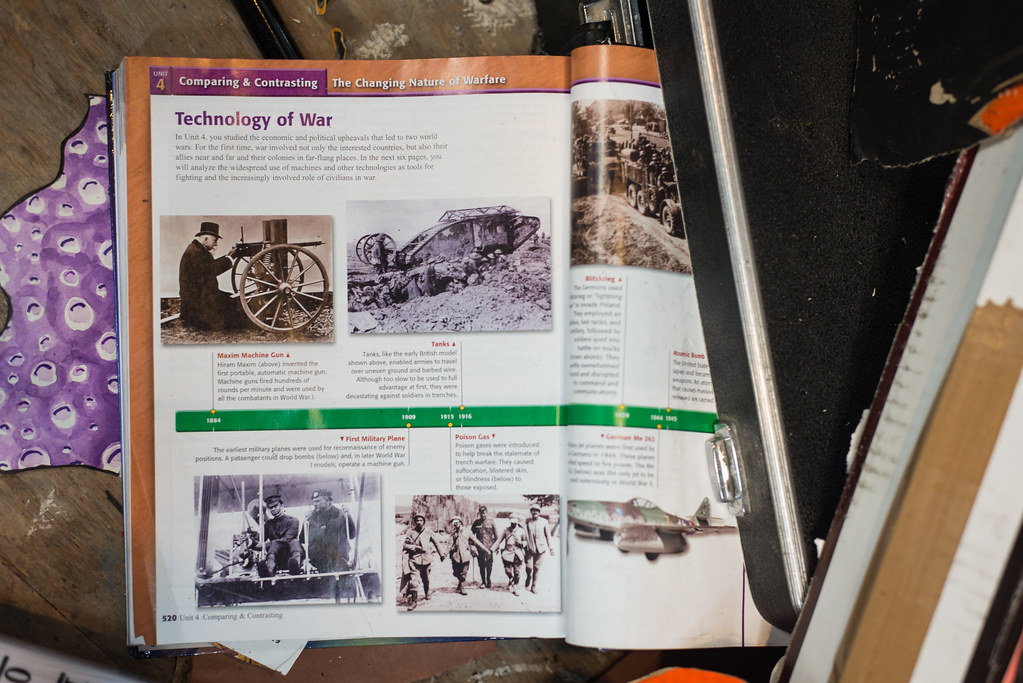

In addition to the calendar, hints of order disrupted the disorder—a tape measure, clocks in the video, lines of little cardboard garbage trucks, and a history book casually opened to the Timeline of War. Mercer called it a “subtle way to get to the ethics of the issue,” which is probably true, because I wouldn't have gotten it if he hadn't been there to explain.Image: Derek Mead

“People associate garbage with chaos and collapse, but garbage is very crafted—it's separated, sorted, landfills are aerated,” Mercer said. “It has a real narrative value.”Garbage is an unsightly, smelly aspect of the future. Most of today's innovations that deal with it are about getting it out of our sight as swiftly and efficiently as possible.For me, tossing a bag of dog shit in the trash can on the corner is the liberating end of my relationship with it, that's where the systematic, organized effort to get it out of my sight begins, and as long as it doesn't find its way to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, our (collective human) relationship with it doesn't end there.The actual ground of much of Lower Manhattan is made of garbage. I used to fly kites on a hill in Chicago which only existed because it was a quarry that had been filled with garbage.Image: Derek Mead

All it takes is a walk up one of those Manhattan streets after a snowstorm or, god forbid, during a sanitation workers' strike to remind you that, as far as we know, our society is only possible because of this circulatory—or maybe, digestive?—system. Our way of life is untenable without it.Thing is, as Mercer imagines it, and as projected by the World Bank, life is going to be untenable if as more and more people live like I do.