I haven't thought about spam for years.I mean, I know it's there, in comment sections, and swept deftly under the rug of its eponymous folder in my email account. But I haven't heard from any desperate relatives, passports lost on a trip to paris, in more than a year. And don't think I've had a single ad for Viagra, real or fake, hit my inbox in recent memory. As far as I'm concerned, spam is a non-issue.

Advertisement

"Spam will be a thing of the past," Bill Gates declared in 2004 before the World Economic Forum. Even as he praised Google and admitted to Microsoft's missteps in search, Gates wielded his trump card like a tech boss: Microsoft would have the problem licked in two years, relying on basic word puzzles—either human, or cycle-eating computational ones—and what essentially mounted to stamps. Basically, the idea was that if you marked something as spam, the sender would get dinged at a predetermined rate. Email would be free for users, but abusers would end up paying for the infrastructure costs they incurred, as if they were relying on the Postal Service. Filtering, said Gates, would "not be the magic solution."The stamp idea was shelved almost immediately, and while CAPTCHAs have taken off as a great way to slow down automatic signups, they never got implemented inside the inbox. I take that back — Gmail's Goggles make you solve a math problem before sending an email, in order to prevent the regret that comes after the influence of alcohol. I had it going for a week in an attempt to shore up my arithmetic.But Gates's biggest miscalculation was the filtering one. He couldn't predict the rise of Google's killer e-mail app either. (He did praise the "high level of IQ" at Google's research team, but promised, "we will catch them.") In fact, thanks to Google, filtering has developed much faster than many had predicted.

Advertisement

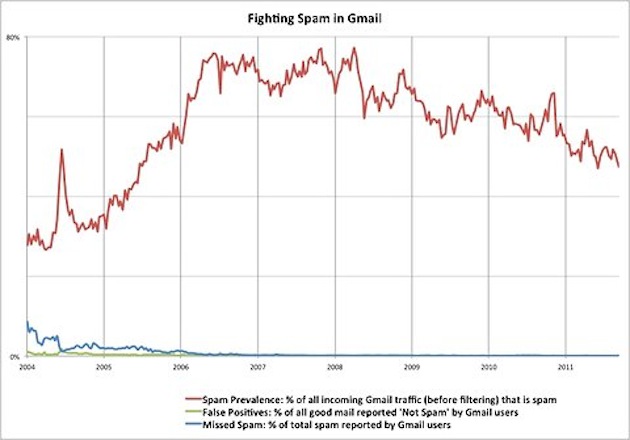

A Google PR rep explained that well under 1 percent of messages coming into your account are marked as spam — but those messages, the ones that end up in your spam folder, are only the missed spam. More than 50 percent of emails to the system never make it anywhere near your inbox.

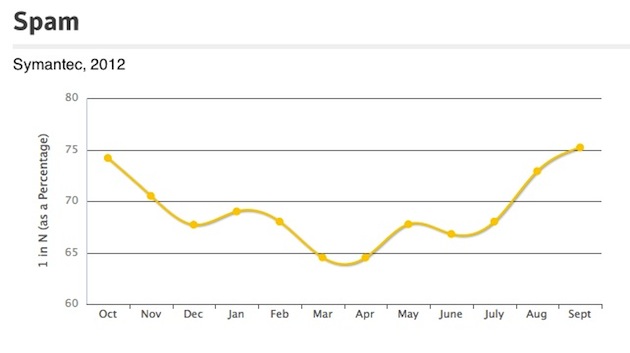

And so, in a way, Bill Gates wasn't so wrong after all. Email spam really is pretty much gone.Except, of course, that it isn't. According to the Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group, an alliance of Internet service providers and other telecom companies, "abusive email" sent last year ranged from about 90 percent to 88 percent.But a recent check of my spam folder got me thinking. Just over half of the messages identified as spam were not, in fact, spam. Most were daily deals ads, from fab.com, and Groupon. A bunch were comment moderation notices from a website where I'm supposedly an admin.In 2011 Osterman Research released a report claiming that false positives in spam filtering cost US businesses $10 billion lost in productivity, and while numbers from security firms are generally suspect, I have to believe this is a problem that costs money. According to Google, Gmail's filtering has a false positive rate of less than one percent. But given how important some emails can be, that's still a lot of potential loss.Google won't say how many emails they process a day, but they will say that they host 425 million active email accounts. If each account gets 25 emails a day, that's 10,625,000,000. If even a hundredth of one percent are false positives, that's 1,062,500 emails mistakenly identified as spam every single day. Granted: I made up the average daily email rate, and, I guessed at what "well under 1 precent" might mean. Regardless of what the real number is, that's a lot of ham.

Advertisement

But still: ignoring all the deals I was missing, though, there was a lot of spam in my spam folder.WHAT IS THIS SPAM YOU SPEAK OFThe Spamhaus Project (which acts as an international anti-spam watchdog and notably helped with the big takedown of the Grum botnet recently) defines spam as "any unsolicited bulk email" — a definition broad enough to cover Nigerian princes, British estate attorneys, Canadian pharmacies, and annoying friends who add you to their mailing list without asking nicely.In the United States the CAN-SPAM Act doesn't so much define spam as lay out legal ways to send commercial emails, which is basically this: As long as companies adhere to three categories of compliance (the ability to unsubscribe, clear content, and good sending behavior), they're totally in their license to spam the living hell out of you.So – what's clear content and good sending behavior mean, exactly? According to the CAN-SPAM act, non-spam meets the following criteria:

- Content compliance

- Accurate from lines (including "friendly froms")

- Relevant subject lines (relative to offer in body content and not deceptive)

- A legitimate physical address of the publisher and/or advertiser is present.

- A label is present if the content is adult.

- Sending behavior compliance

- A message cannot be sent through an open relay

- A message cannot be sent to a harvested email address

- A message cannot contain a false header

Advertisement

This is why places like www.targetedemailads.com, which offers a campaign of 1,000,000 emails for $500, can advertise legally with AdWords. According to Spamhaus, the US based Direct Marketing Association explicitly approves of spam. They did not respond to a request for clarification.

Of course, if you make the mistake of living in the United States and not adhering to the CAN-SPAM Act, you could very certainly end up in jail. In 2009, for instance, Alan Ralsky got four years for a massive fraud scheme wherein he pumped the price of a Chinese penny stock. Commending his sentencing, U.S. Attorney Terrence Berg made it seem like the whole affair was a win for the good guys and a loud message to anyone who would dare to press send a million times: "With today's sentence of the self-proclaimed 'Godfather of Spam,' Alan Ralsky, and three others who played central roles in a complicated stock spam pump and dump scheme, the court has made it clear that advancing fraud through abuse of the Internet will lead to several years in prison."By then, Ralsky, who is still serving time in a federal prison in West Virginia, had already encountered another form of justice: after a December 2002 interview with The Detroit News appeared on Slashdot, the address of his newly built home in Michigan landed on the site too, inspiring hundreds of readers to sign him up for advertising mailing lists and free catalogs. "These people are out of their minds," he told the Free Press at the time. "They're harassing me."

Advertisement

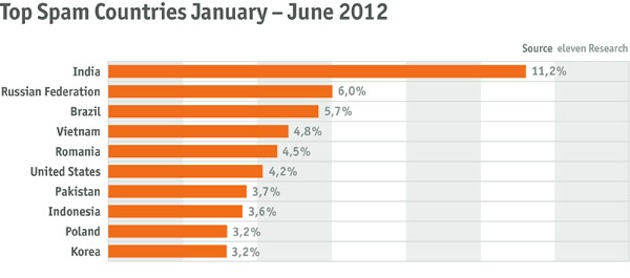

But this is beside the point. I could quasi-legally send out a million spam emails urging people to read my article about spam, but it would be drop in the global bucket — most of which, from knock off watches to prescription free drugs, is on the wrong side of domestic and international law.THE NUMBERS OF THE NUMBERS GAME

With spam, we've got something that everyone hates, something that is illegal to varying degrees around the world, and something that has, for the internet, amazing longevity. Why?Because it pays. This is both a general truism (if spammers weren't making money, they'd be doing something else) and also an empirically derived assessment. According to "PharmaLeaks", a paper presented at the recent Usenix Security Symposium, top tier online pharmacies, for instance, bring in millions of dollars a year in revenue through messages that have been filtered — or not — from your inbox.BOTNETS, THE ZOMBIE SPAMMERSThere may not be a Spammers Associated issuing quarterly reports, but a few academic researchers have been doing this research for years, and they've established an incredible amount of knowledge about the economics of the spam industry — from click-through rates to affiliate structures – and the technology that powers it.In "Spamalytics", a 2008 paper by scientists at the University of California at Berkeley and San Diego, the authors describe infiltrating a botnet, a network of hacked computers capable of spamming millions and the elite spammer's weapon of choice, and using it to send out spam linking to their own, fake, online pharmacies. As academic experiences go, actively tinkering with illegal spam operations sounds pretty exciting. Chris Kanich, now an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, confirmed that it was.

Advertisement

"It was a good experience," says Kanich. "We saw that [the botnet, called Storm] had this vulnerability that would allow us to take our measurements — and that was a very good motivator to be like 'we have to get up to do this experiment, because he could push a new update tomorrow that would completely invalidate our ability to to these measurements' — it was pretty exciting definitely — though there were no bunkers involved."The upshot: In 2008, the average conversion rate (from click to shopping cart) for pharmacy spam was 1 in 12,500,000. Or put another way, if every US citizen got one spam message, 28 of us would be to blame for supporting the industry. This is, of course, tiny, but so was the sample. The 350 million messages they sent were dispatched by less than 2 percent of the botnet. And Storm was just one of many.There's a distinction to be made between advertising spam (watches, Viagra, whatever is just slightly illegal enough that people can't buy it on the street) and what I would term malicious spam (scams, phishing attacks, malware, you name it). That the second is counter-productive to society I don't think anyone will argue. Malicious spam seeks to profit from another's loss, and that's just not nice. But it's easy to see advertising spam (especially pharmacy spam) as essentially benign. If you don't want to satisfy your partner with amazing, herbal supplemented, superlatives, just don't click on the ads. They're not hurting anyone.

Advertisement

Well, they might be. Real (non-spam) advertising is subject to a handful of laws, things like the whole prohibition on ""unfair and deceptive acts or practices in commerce." (15 U.S.C. § 45.) So those promised of massive growth, or satiated partners might not be quite legal. But there's a line to be drawn between shady and morally bad.

How a botnet turns computers around the world into spam-sending zombies (Wikipedia)Not to mention, notes Kanich, that if you're buying something with a credit card, you have all the control. If the pills don't show up, or if they turn out to be Tic-Tacs, you just get your credit card company to reverse the charge. At that point, spam is no worse than the Rite-Aid coupons I have to recycle once a week.But Vincent Hanna, a researcher with Spamhaus isn't worried about differentiating the bad from the not-that-great. "Obviously some are more dangerous than others, but in the end, it's all email that you didn't ask for," he says. "Our main reason for existence is trying to make sure that you get as little spam as possible. And if that's an email selling Viagra or a fake university diploma or something with a malicious attachment. If you want a clean inbox then you don't really care what it is. You just want it to be clean."We've posted about botnets before (here, and here) but this seems like a good time to bring up a crucial point — botnets, and really, most of the innovation in the malware industry — if I can call it that — can be linked to spam.

Advertisement

VERY GUERRILLA MARKETINGAs the security industry has developed more robust filtering techniques, spammers have had to develop new ways to get around them, in a war of escalating workarounds and developments. With the rise of IP blacklists, new strategies had to be executed, and they're using your computer to do the dirty work."It used to be very isolated thing," Hanna explained. "You had spam and you also had old school viruses on your computer. As time progressed, due to various technical innovations and ISPs getting smarter, the spam and the virus problem became very much a combined thing. Most of the spam we now get as an internet user was sent from a computer that was infected with some sort of virus, or botnet. These things have very much grown into each other."Furthermore, while email is free for you and free for me as long as I squeak in under Gmail's new 10 GB ceiling, it's not really free. Those emails take up real space on physical servers — servers that have to be kept running, and kept cool.If spam makes up even 50 percent of all email, think about the greenhouse gas emissions we could cut by getting rid of it. Add in the amount of time and money that companies spend fighting spam (or buying anti-virus software) and the relative savings from getting rid of all those false positives, and the eradication of spam seems like a pretty good goal for humanity to shoot for.

Advertisement

It is important to note that at this point there has been enough development in the online pharmacy world that the pharmacies are contracting out their spamming operations.Put another way: they've hired marketers, just another cost of doing business. One of the things that Pharmaleaks helps to demonstrate is the sheer scale of these operations. Spammers are paid on commission, making a bit under 35 percent on average. That's high. But they're only getting paid when the companies make money, under what's called the "partnerka" model, named for the Russian slang for a mix of private and semi-public affiliate groups that form to facilitate cybercrime activities. And they're also assuming much of the risk in terms of legal repercussions. In 2007, in return for sending lots and lots of porn, two Americans, Jeffrey A. Kilbride and James R. Schaffer, were both sent to prison under the Can-SPAM Act.Barriers to entry in the pharmacy market are high, setups are complicated, and startup costs not insignificant, but competition in the spamming market is pretty well perfect. If you can build a better botnet, the rogue world will beat a path to your door.In the recent takedown of the Grum botnet, Spamhaus spent months working with a company called FishEye Security. They tracked down the command and control servers, and, one by one, working with ISP's, they shut them down. Grum was responsible for 18% of the world's spam, some 18 billion messages a day. So getting rid of the botnet should significantly cut down on global spam, not to mention effectively de-zombifiying all those infected computers. Instead of going (virtually) door to door with a scrubbing program, the people who took down Grum took a malignant piece of code and turned it into a benign byte or two. The takedown was a major coup, no doubt about it.

Advertisement

But that doesn't stop another spammer, another botnet, from stepping up to the plate.

Chris Kanich, assistant professor at U Chicago, is a scholar of spam. Bottom: Steve Linford, founder of the Spamhaus Project (Insight / Corbis)A better way to make spam go away would be to make the whole enterprise more expensive. One of the great things to come out of the academic research is the knowledge that, despite drool-worthy gross revenues, profit margins in the online pharmacy business are actually pretty low.GETTING TO SPAM INBOX ZEROBrian Krebs started writing about cyber security for The Washington Post, and today maintains the KrebsOnSecurity Blog, which is a consistently excellent resource for all things cyber crime related. He's listed as a co-author on the PharmLeaks Study (largely, he wrote for contributing much of the data used in the study), and he told me that focusing on the money is where the good guys can win:No one solution is going to work, and maybe a combination of solutions is going to eliminate the problem. But I think what's been most useful and interesting about the research from the UCSD guys is that it shows that these are businesses … They have balance sheets and profit and loss statements. They are very conscious about what each part of their business costs them …For these organizations, their profit was just a fraction of overall revenue — between 10 and 20 percent. That means that if some of the components of their business — from shipping to supply costs — go up significantly, it would put a decent dent in their profits. If they spend about 12 percent of their revenues on shipping, and all of a sudden they have to spend 20 percent on shipping, that could make the business near unprofitable.

Advertisement

If you can increase the cost for the bad guys, you make a lot of this stuff unprofitable for them and they'll find something else to do.Krebs own work, which includes a fantastic series profiling some of the major players in the rouge pharmacy world, suggests that increasing costs, or better yet, putting spammers or pharmacy owners in prison, will not be easy.A clear weakness, right now, is the fact that there are only a few banks willing to process credit cards for the pharmacy operations. If those could be convinced to stop it seems like that would be the end of the business. Except that, suggests Krebs, "as the traditional means of accessing the credit card processing network dries up you're going to see a higher demand for compromised merchant accounts, and then you're going to see some of the approaches we've seen in the botnet fields come into play."At that point, the game goes up a notch. Another cost gets added to the balance sheet, and maybe more spam needs to get sent because of it. The industry keeps getting bigger, the drain on the economy larger. Already the cost of dealing with spam is orders of magnitude more than the profit spammers and their associates are making. But, there's not much else you can do. The spammers will interpret damage as censorship, and work around it.But there are a couple solutions.

George Burns and Gracie Allen in an old ad for Spam (Spam Museum in Austin, Minnesota)We could make it really illegal to send or click on spam advertisements. People buying Viagra online could be put in jail. And then, when the market changed to something else, we could change the laws and put people buying that in jail too.We could start charging for email. Seriously. That would make the problem go away. And imagine how much easier it would be to achieve that zero-inbox gurus are always talking about.Or we could make it legal to advertise for illegal things. If the return-on-investment is higher for Facebook ads than for spam, and Viagra peddlers were allowed to advertise on Facebook (which is already apparently full of seniors), maybe they would just start hiring real marketers and forget about the whole spam thing.Then again, General Motors didn't think there was a future in Facebook advertising, so it stopped altogether. I wonder if we'll start seeing personalized messages promising "Buicks to make your partner scream."The offer might already be in your inbox somewhere. But check quick — it might only be around for a limited time. "With each takedown we learn more and we manage to raise the price," Hanna says. "So while it may be a whack-a-mole, every time you whack a mole, it's getting more expensive [for spammers] to get back to business."